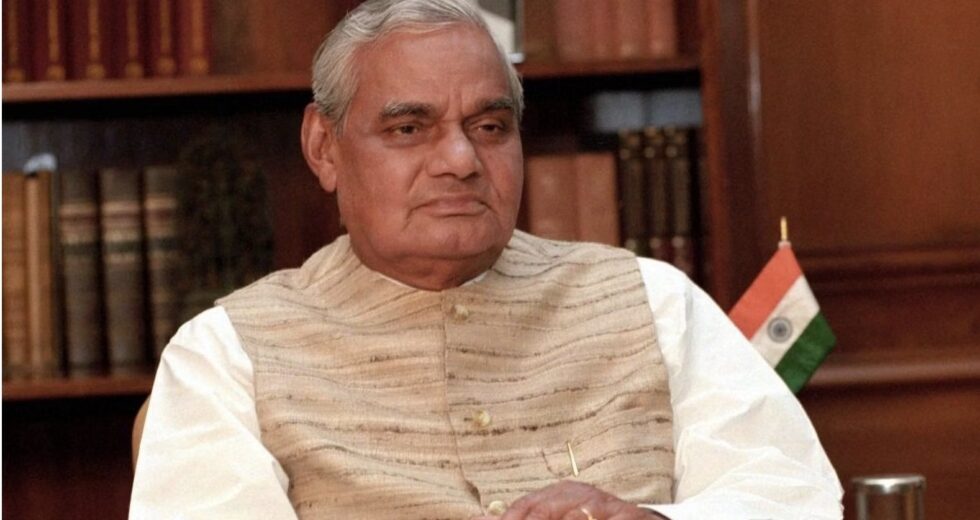

Exploring the Enigmatic Life of Atul Bihari Vajpayee – A Review

Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977 – A review

By Narada Roy

To say that Atal Bihari Vajpayee has been a political enigma is something of an understatement. This ambiguity has led to the prevailing notion about his life that he was a voice of moderation in a right-wing Hindu movement that morphed into the ruling party of India. In his well-researched biography, Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977, author Abhishek Choudhary goes to great lengths to expose that view as a myth.

Choudhary exposits on Vajpayee’s intellectual curiosity and inclination towards learning, despite his mediocre grades in school. We learn that his schooling and college up till his post-graduation was in Hindi. He writes poems that make him popular among the people who followed RSS, and this communicative capability in Hindi remains a powerful impetus in his ascent after he joins the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) as a full-time pracharak.

Vajpayee goes on to be personal secretary of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, and later makes him a promising member of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS). While not a founding member of the party, he was influential as an editor of the RSS publications. His apprenticeship in the RSS is depicted as an arduous one – on in which he travels to towns and villages in Uttar Pradesh without money and comfort. And the same trend continues when he is tasked to bring out the various RSS publications, from Rashtradharma to Panchajanya to Veer Arjun.

In many ways he played the role of a missionary worker advancing the cause of RSS. It would be inaccurate to call it Hindutva because Vajpayee did not seem to abide by the basic tenets of Hindutva; rather, he espoused his own version of the movement. He used the Hindutva arguments in his writings, in his speeches and in his poems but he never gave the impression these were his foundational beliefs. This flexibility of principle enabled him to evolve, change his arguments as the occasion demanded – and this was critical to his advancement and positioning as a leader in the BJP.

Accordingly, the same person who could refer to Muslims who remained in India as fifth columnists in 1948 could then argue that there is need to admit Muslims into Jana Sangh, something that the fundamentalist Ram Rajya Parishad refused and thus broke the possibility of bringing together all the right-wing Hindu political organisations. It was on this point that Syama Prasad Mookerjee left Hindu Mahasabha. And Vajpayee would object to Nehru clubbing Hindu Mahasabha and Jana Sangh.

In the 1950s, he did not have to wait long to be inducted into the political structure because there was not too much competition and he brought to the job the credentials of a RSS pracharak. And there were not many takers for a parliamentary contest in the fledgling party. So he was fielded for the Lok Sabha by-election for Lucknow as Vijayalakshmi Pandit resigned when she was given an ambassadorial assignment, but lost the election. In 1957, he won from Balrampur though he lost from Mathura.

It is his early start in parliament that made him understand that issues were of greater relevance than ideological positions, and he was a quick learner. So as a man from the opposition benches, it was his job to corner the government on any and every issue. Vajpayee had to diversify his repertoire. But of course he was most comfortable with the Hindu cultural nationalism issue. He had come far from the days in the late 1940s when he found the song from Raj Kapoor’s Barsaat song, “patli kamar, tirchchi nazar” to be vulgar and corrupting.

The most interesting part of Vajpayee story in this volume — it is a two-volume work — is his ambivalent relationship with Nehru, with whom he crossed swords on the floor of parliament, but he also looked up to him. And Nehru seemed to have been indulgent towards him too as when he put Vajpayee on the Indian delegation to the UN in 1960 and Vajpayee was all admiration for Nehru at the UN, and he also toured the country, watched the Nixon-Kennedy televised presidential election debate, and discovered Chinese food which remained his favourite for the rest of his life.

This book examines the imagination and the ideological neurosis that determine the world view of the Hindu right and dominate our lives in more absolute ways than in Vajpayee’s lifetime. Equally, there is acknowledgement of the social origins of the RSS and the Jana Sangh that Vajpayee served so well. He was quintessentially a Hindi belt Brahmin with a talent for quick poetry and prose, and he worked very hard and struggled in his youth to launch publications that could share the RSS world view.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine