Another Global Calcuttan Makes Booker Shortlist

Just a Year After Jhumpa Lahiri’s nomination, Neel Mukherjee’s The Lives of Others is among short-listed titles for the MAN Booker Prize

By S.B. Veda

CALCUTTA – As news circulates that Calcutta-born novelist, Neel Mukerjee, has been short-listed for the prestigious MAN Booker Prize for his recent novel, The Lives of Others (perhaps giving the current inhabitants of this city another reason to ignore its cultural decline) the jury for the prize seems as nostalgic as this writer for the Calcutta of old.

For the second year in a row, a book set in Calcutta in the 1960s has made the shortlist for the prestigious award (though, to be fair, Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland, shortlisted last year, was set partially in USA but begins in Calcutta).

Leaving aside their common cultural background, the two novelists have been compared for the subject matter in their recent works.

While The Lowland focuses on the lives and legacies of two brothers, Mukherjee’s The Lives of Others, though set during the same period, features a vast cast of characters and can be described as two or three novels within a single work.

With novelists tending to focus on a single or few characters, and the length of books decreasing (in general) Mukherjee’s achievement of intertwining so many narratives together – and this, so successfully, seems that much more monumental. He does so in a manner that easily allows the reader to permeate the thoughts of various characters. It is a fluidity of voice that is both subtle and effective.

The book had been well received, after being published earlier this year, described as “masterful” by one prominent reviewer, “engrossing” by another. MAN Booker Prize winner, A.S Byatt, no less, acclaimed the prose in a recent piece for The Guardian, describing its author as being, “as good with flesh and blood – sex, sickness, murder – as he is with stems, flowers, rice… Neel Mukherjee terrifies and delights us simultaneously.”

To pick up on Byatt’s point, Mukherjee does so with deftness and precision (though perhaps, at times slightly, overdoing it) opening the novel with a prologue describing the horrific murder-suicide of a frustrated farmer and his family; this runs counterpoint to his narration of how, in one home, three generations of a bourgeois Bengali family wake up and start the day. The antithetical nature of the two juxtaposed scenes jump of the page – this from the very beginning of the novel.

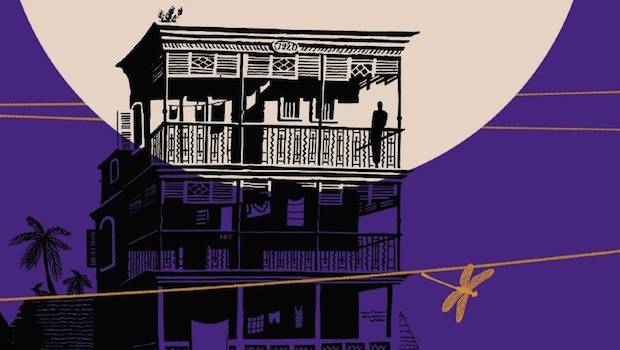

The Ghosh family, members of which figure prominently in Mukherjee’s tale of tales, enacts the complexities of Indian joint family life in all its mundane and yet compelling intrigue. The Patriarch, Prafullanath, debilitated by a stroke stays with his quarrelsome wife, Charubala at the apex of the Ghosh pyramid both figuratively and literally (staying on the top floor of the house and also wielding the most sway).

The families of their four adult sons reside with them in this house, inhabiting different floors and virtually different existences (at least in their minds) until circumstance causes their worlds to intersect on a routine basis.

The parents’ glossy recollections of the favoured Somnath, their youngest child, now deceased, are a sharp contrast to their treatment of his widow, Purba, who lives in a tiny room (little more than a cleaned out storage room) on the ground floor with her children, Sona and Kalyani. They are left to survive only on plain rice, potato and lentils, except when others in the household can spare a few scraps from their table, sending leftovers down to them. The cruelty of their circumstance is quite nearly lost on the other members of the family. Purba is little more than a glorified servant, monitored hawkishly by her belligerent mother-in-law.

The matriarch, Charubala fights ceaselessly with her dark-complexioned daughter, Chhaya (a bit too on the nose is this shadowy name, maybe?); she is too substantial on the inside and lacking on the outside to attract a suitable husband, leaving her spiteful and embittered – at one point dumping an entire bottle of nail polish on new clothes to be shown off at Durga Puja celebrations by her niece and sister-in-law. Joint families are rife with melodrama; for one who is unfamiliar, this may seem over the top – but it isn’t, really.

Among the grandchildren, two stand out: Supratik and Sona. The former’s reactionary social conscience and anger lead him to leave home and join the Marxist agitation, which originated in Naxalbari, called the Naxalite movement, much in the same way that Lahiri’s Udhayan does in The Lowland.

Instead of focusing on the consequences of a young man’s life cut short in pursuit of revolution as Lahiri did, Mukherjee’s novel spends ample time on the life of the revolutionary as told through letters to his aunt with whom he is smitten. His calling is replete with challenges, and ultimately the idealistic lens through which he views the struggle becomes murky and his outlook dark. This could have been a novel in itself, just as the story of Sona, whose genius in Mathematics redeems both him and his mother Purba, has the substance for a stand-alone piece of work. The smooth layering of these and other plots in this remarkably vivid period piece sets Mukerjee’s work apart from most, and puts one in mind of Vikram Seth (another ‘Global Calcuttan’).

Lahiri’s novel attempts to draw parallels between changes taking place across across seas and deals with familiar themes of displacement and isolation; Mukherjee’s is a distinctively Bengali story, depicting life in 1960s Calcutta where melodrama runs high, and the shadow of Tagore looms large.

Lahiri’s novel attempts to draw parallels between changes taking place across across seas and deals with familiar themes of displacement and isolation; Mukherjee’s is a distinctively Bengali story, depicting life in 1960s Calcutta where melodrama runs high, and the shadow of Tagore looms large.

The Ghosh family’s paper business is a metaphor for the state – once vibrant, the centre of activity and influence during the British Raj, is in decline. Independence has brought new Sahibs to power, brown ones – but done nothing to lift the poor out of misery nor compellingly motivate the rich to spread their wealth. And, when the absent monsoon fails to quench a burning thirst created by the relentlessly punishing sun, it leads to violent uprising, which both Mukherjee and Lahiri examine but in strikingly different ways.

Lahiri’s characters live in the shadow of revolution: they are left behind by the actions of the rebel. In Mukherjee’s novel, we learn of the struggles within the struggle, firsthand. Both writers depict characters reacting to the negative space left by a powerful but absent personality. In The Lowland, activist Udhayan is dead. In The lives of Others, the story of Supratik, his analogue, unfolds almost as it happens, and in his own words; as well, it infuses some quanta of hope in the worried minds of family members that he may ultimately return.

While Lahiri’s skill lies in depicting the mundane with both curiosity and delight, effectively placing the reader within the corridor of a singular space-time, Mukherjee’s prose delivers a stream of bold images, ideas and dialectics with striking acuity, accentuating the extremes of experiences through the depiction of often shocking contrasts.

The way in which Mukherjee describes morning in Calcutta reads like moving pictures and sound, “She hears the scouring sound of a broom sluicing out with water some drain or courtyard. Someone is cleaning his teeth in the bathroom of a neighbouring house – there is the usual accompaniment of loud hawking, coughing and a brief one-note retch. A juddering car goes down Basanta Bose Road with the unmistakable sound of every loose vibrating component about to come off – a taxi. A rickshaw cycles by, the driver relentlessly squeezing its bellows-horn. Another starts up, as if in response. Soon an entire fleet of rickshaws rackets past, their continuous horn shredding what little sleepiness remains of the morning.”

His narration of the bustling infancy of the day is like a symphony of activity: the sluice of the broom gives way to brushing and hacking, and the ambient noise taken over by the rickety sounds of a yellow cab, which is followed by a continuum of ‘paaank’ coming from the rickshaws. And then we are awake. This is Calcutta in the late 60s and Mukherjee’s prose beckons us to join him within its borders.

They are sounds that are heard in the distance, today. In most parts of Kolkata, one is largely insulated from the brushing sounds of neighbours, largely absent is the rickety sound of a single taxi as increasingly, one hears a vehicular roar streaming by, instead. And the cycle rickshaws, they’re still around but bellows are more often drowned out by the piercing, deafening honks of motorbikes.

In this case, the writer describes a city that was, its sounds often jarring, repulsive – and yet in the writing we feel a certain longing.

Mukherjee and Lahiri are both extraordinarily gifted artists, whose works, if not ostensibly being about Calcutta (as Ghosh’s recent novel is but Lahiris haven’t typically tended to be) can be certainly characterized as inspired by or born of the city. Interestingly, though – I do not speak of Kolkata. For the stories of Neel Mukherjee and Jhumpa Lahiri are set in vanishing terrain – a space that has become occupied by the concrete of a newer metropolis, with a rigidity, and thickness about it, causing the vibrancy associated with its predecessor to (largely) dry out. It is as though much of the creative life blood of this city, once pumping through the hearts of a spirited confederacy of voices has evaporated, only to be sprinkled over an Earth that is tread upon by foreigners – but the substance is much the same: the culture of Rabindranath, Bankim, Saratchandra.

Neel Mukherjee and Jhumpa Lahiri have, indeed released their imagined homelands beyond physical boundaries and moved their culture beyond borders. They have helped make the culture of Calcutta universal – and we are better for it.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

Congratulations Neel!

I add my felicitations. Though Jhumpa’s novel was strong, Neel’s is better, and with any luck should win. It deserves so.

Is this the beginning of a new Bengali Renaissance? But a ‘Global’ one? That would be great. I like your tagline, culture beyond borders. Bengalis are doing so well abroad!

In some ways the future of Calcutta culture lies abroad. Its as good or bad as one thinks of it but is seems the reality.