In the Aftermath of the Dhaka Massacre

In their search for meaning, they have been twisted to believe that by killing, they can not only achieve the greater good but reach a status of supra-mortality – that of the martyr. They are doing God’s work. And it gives them a rush – no less potent than methamphetamine, cocaine or heroin. Extremism is a form of addiction, the deadliest kind.

For more coverage see:

Ishaan Tharoor on The worst alleged ISIS attack in days is the one the world probably cares least about

Lisa Curtis on Bangladesh Attack Shows Depth of Country’s Extremist Problems

David Rosenberg on Tourists, students among 22 dead in Bangladesh slaughter

Rafia Zakaria on How the Dhaka Attack Reveals Extremists’ Use of History

And, Bangladesh PM Hasina decrees mourning after cafe attack

By SB Veda

I was aghast when I heard about the massacre at the Dhaka bakery The Holey Artisan. Having come to terms with the idea that due to increasing attacks against Hindu and other religious minorities as well as religious dissenters by Islamic terrorists in Bangladesh, that violence had become the new reality in the Secular Muslim state that was once part of British India – but the sheer brazenness of this mass murder, within the affluent neighbourhood of Gulshan was nothing short of horrifying.

I’d been there less than two years ago as a speaker/delegate of Dhaka’s premiere literary event, Hay Festival Dhaka. Though I’d heard of The Holey Artisan, it wasn’t on my itinerary of places to go though I was in the posh neighbourgood of Gulshan where wealth locals, diplomats, and foreigners tourists coalesce.

One of the founding directors of the literary festival, entrepreneur and poet, Sadaf Saaz invited delegates, myself included, to her home in Gulshan for a dinner associated with the occasion in 2014. My wife, who was my plus one to the dinner wasn’t feeling well, so we cut out early to get some air. Once outside, we thought we should stroll through the quiet neighbourhood at night, taking in the serene atmosphere near Gulshan lake. Amidst palatial homes and high security flats, the place seemed nearly impregnable, airtight. Not two years later, it appears that nowhere is safe.

WHAT HAPPENED

The terrorists, reportedly seven of them, apparently entered the bakery during the evening as people were sitting down for dinner. Witnesses reported hearing a series of gunshots Friday night as people raced for cover.

Some of those who fled reported that the gunmen were shouting, “Allahu Akbar,” or “God is great,” a phrase used in the Muslim call to prayer but which is all too often appropriated by terrorists to herald the onset of their savagery.

The standoff ended nearly 11 hours later, on Saturday morning, after commandos stormed the cafe, killing six attackers and capturing one. Thirteen hostages were rescued, authorities said.

The bodies of 20 hostages were found on the floor, mostly hacked and stabbed to death. The death toll would reach 22.

The attackers used guns, explosive devices but mainly to create an environment of fear. The murders, like so many in the city were carried out by “a lot of sharp domestic weapons,” said Brig. Gen. Naeem Ashfaq Chowdhury of the Bangladesh army.

Indeed, what much of the press is not reporting is that earlier in the day, a Hindu Temple worker was hacked to death in Jhenaidah District by three men on a motorcycle who launched upon him as he walked on the highway adjacent the temple where he worked. The killing mirrored that of a seventy year old Hindu priest similarly hacked to death at a rice paddy field near his home, last month.

Bloggers, atheists and members of the LGBQT community have been similarly attacked with machetes, knives, daggers and other bladed weapons that law enforcement authorities in Bangladesh rather casually refer to as “sharp objects.”

At the bakery, during the siege, the gunmen separated the Muslims from the non-Muslims. The Muslims were given food and water. As dawn approached, the attackers ordered the remaining staff to prepare a meal so the Muslims could eat before beginning their Ramadan fast.

According to The Independent newspaper, which quoted the father of one of the hostages, the terrorists demanded the hostages quote from the Koran. Those who could not were tortured.

Indeed, The Bangladeshi newspaper, The Daily Star, quoted a captive’s parent, Rezaul Karim, stating, “The gunmen were doing a background check on religion by asking everyone to recite from the Quran. Those who could recite a verse or two were spared. The others were tortured.”

The Independent reported that an ISIS-affiliated propaganda agency released photos from inside the restaurant during the raid, appearing to display the bodies of women and men on the floor in pools of blood by overturned tables and chairs. Those who’d been able to recite verses from the Koran were spared that fate, having been treated well and given food.

One of the first victims to be identified was an Indian Jain girl named Tarishi Jain who’d just returned home from College in the United States for summer vacation. She was used to frequenting the bakery, it being located in her neighbourhood of Gulshan, and had gone to the cafe with two friends for its delicacies. Her father Sanjeev had moved the family to Dhaka for his business. He is one of the garment entrepreneurs who’d prospered over the past fifteen years as Bangladesh became a global hub of the garment weaving industry, supplying major shops all over the world including the discount retail giant Walmart.

One of the first victims to be identified was an Indian Jain girl named Tarishi Jain who’d just returned home from College in the United States for summer vacation. She was used to frequenting the bakery, it being located in her neighbourhood of Gulshan, and had gone to the cafe with two friends for its delicacies. Her father Sanjeev had moved the family to Dhaka for his business. He is one of the garment entrepreneurs who’d prospered over the past fifteen years as Bangladesh became a global hub of the garment weaving industry, supplying major shops all over the world including the discount retail giant Walmart.

A student of the Institute for South Asia Studies of the prestigious University of California at Berkeley, Jain reportedly was intent on making a difference in the region, improving living standards, and helping to eradicate poverty. Her dreams were not just cut short; she faced a tragic and gruesome end. According to sources, she was among the hostages who had likely been subjected to torture before being killed. “That was apparent from the injuries,” a source said.

The foreigners killed includes: Nine Italians, seven Japanese, one US citizen and an Indian. One Italian is still unaccounted for.)

WHO WAS RESPONSIBLE AND WHAT’S GOING ON IN BANGLADESH?

Whether or not ISIS was, indeed, responsible, what the world needs to wake up to is that, in Bangladesh, there are ample ‘usual suspects.’ It is telling that the perpetrators spared those who could recite the Koran, for since the war of independence, Pakistani Islamists had considered Arabic-speakers to be ‘pure’ Muslims and Bengali-speakers to be impure (being influenced by Hindu culture). Pakistani soldiers justified an organized campaign of rape in order to ‘improve the gene pool,’ – their bid to the make population more genetically predisposed to accept God (some 400,000 women were raped during the war).

Bangladesh had contended that three million died in the Pakistani genocide in what was to be a country defined by linguistic identity more than anything else. But the Islamists didn’t leave, and they fought to impose a Muslim identity on this constitutionally secular state. It didn’t help that those who’d been forced to flee to India and elsewhere abroad in the largest emergency migration of any peoples in history (around 30 million souls) came back to a place in which rape victim had to live alongside rapist. The victorious secularists speaking their impure ‘bhasha’ had to live with the defeated ‘real’ Muslims whose tongue was that of the Prophet, himself – and the divide was never breached.

Until current Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina (having lived in exile herself after her entire family, save her sister, was murdered in a bloody coup by those with allegiance to the Islamic ideology that created Pakistan) started prosecuting war criminals (these included home-grown collaborators, who had cut down innocent people, mainly Hindus and intellectuals, during the Pakistani crackdown on its dissident province to the East then known as East Pakistan) the guilty prospered. Even her own father’s killers went about their business with impunity until they were put to death in 2010. Many collaborators got plum diplomatic postings in the UK, US and Canada. (My family may have lived in the same building as one of them in the 1980s as I, blissfully ignorant of all this, played with the children who were my peers.)

Saudi money and Pakistani influence had long been keeping dangerous elements of the Bangladesh population radicalized. Bangladeshi officials say the men belonged to a local banned militant group, the Jamaeytul Mujahdeen Bangladesh (JMB), but are investigating IS links.

There many groups extremist groups from which to choose, though. In addition to ISIS in Bangladesh and Al Qaeda of the Indian Subcontinent, several other terrorists groups operate despite official ban: Harkat-ul-Jihad-al Islami Bangladesh (HuJI-B) ;agrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh (JMJB); and Jama’atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB); and Ansarullah Bangla Team. That’s just what is known, as of now. It is possible new groups have sprouted roots and beginning operations.

The main difference between this attack and others is the social class of all but one of the assailants. They’d come from high class families and had been highly educated perhaps making it easier for them to move unhindered through the high security of Gulshan.

UNLIKELY ASSAILANTS?

Bangladeshis reacted with shock when they learned of the social profile of these young men. In fact, Bangladeshi Information Minister Hasanul Haq Inu told India’s NDTV that “a majority of the boys who attacked the restaurant came from very good educational institutions.

“Some went to sophisticated schools. Their families are relatively well-to-do people,” he said.

One suspect is Rohan Imtiaz, the son of Awami League politician Imtiaz Khan. The young man was reported missing by his parents after he disappeared in December. They recognized him from photographs of the attackers published in local media much to their despair.

“I am stunned to learn this,” said Imtiaz Khan, a leader of the Awami League’s Dhaka chapter and deputy secretary-general of the Bangladesh Olympic Committee.

“My son used to pray five times a day from a young age. There is a mosque just 25 feet from our home. He started going to prayers with his grandfather. But we never imagined this!”

Rohan ran away in December. “When I was searching for my son, I found that many other boys were missing – well-educated boys from good educated families, children of professionals, government officers. I used to share my sorrows with them,” Mr Khan said.

Another dead suspect, Nibras Islam, reportedly attended the campus of Australia’s prestigious Monash University in Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, where the annual fee for a bachelor’s degree is $9,000.

One student there told Reuters that Nibras Islam had appeared a normal student who loved taking photos of himself. He left last year and his social media activity tailed off. He did follow the Twitter handle of one Islamic State propagandist, Reuters reported.

Still another suspect, Andaleeb Ahmed, has also been linked to Monash, having been in Malaysia from 2012 to 2015 and later in Istanbul.

Facebook posts and other sources named three other suspects as Meer Saameh Mubasheer, Khairul Islam Payel and Raiyan Minhaj.

Two of the six, Rohan Imtiaz and Meer Saameh Mubasheer, attended the elite Scholastica public school in Dhaka.

Meer Saameh Mubasheer’s father told local media he feared his son had been brainwashed. “I felt in my heart that he was under someone’s spell. We were good parents yet they took him away from our home,” Mir Hayat Kabir said.

The revelations shatter the commonly held belief that Jihadists come from poorer families. But should these details really come as a surprise? Osama bin Laden was the son of a Saudi billionaire and had studied engineering; his number two, Ayman Al Zawahiri was a doctor who hailed from an elite Egyptian family of diplomats and politicians; David Coleman Headley came from an high-born family in the Pakistan establishment and attended the same school as its military brass before moving to Chicago; and Omar Syed Sheikh (who killed Daniel Pearl and may have wired money to the 9/11 operations head, Muhammad Atta) attended the London School of Economics.

In fact, according to CNN Terrorism analyst, Peter Bergen, even Mohammed Emwazi, AKA ‘Jihadi John’ the savage ISIS beheading executioner, was “a well-born Londoner with college degree in computer programming.” Let’s not forget Major Nidal Hassan, who was a United States army psychiatrist with a comfortable upbringing in Virigina before he went on his killing spree. And then there’s Faisal Shahzad, who tried to blow up a bomb-laden SUV in Times Square on May 1, 2010. He had obtained an MBA in the United States and had worked as a financial analyst for the Elizabeth Arden cosmetics company. His father was one of the top officers in the Pakistani military.

Bottom line: Carefully planned sophisticated attacks require intelligent, savvy and capable agents. This isn’t about poverty – and it’s not a response to globalism (though, I’m sure the globalization of culture is a force against which these people are pushing back). It’s something far deeper that has gone wrong in the souls of these men – there is a deep hole present, which is filled by a religious ideology, which helps them feel powerful, omniscient even. In their search for meaning, they have been twisted to believe that by killing, they can not only achieve the greater good but reach a status of supra-mortality – that of the martyr. They are doing God’s work. And it gives them a rush – no less potent than cocaine or heroin. Extremism is a form of addiction, the deadliest kind.

Such thinking does not exist in a vacuum. As much as politicians like Barack Obama proclaim Islam to be a religion of peace or Mamata Banerjee (closer to home) saying that “terrorism knows no religion,” Islamic texts are cited by these individuals and their Imams as providing the direction for their actions. They may be misguided or have misinterpreted the words. But, why is it these words are so prone to being twisted into weapons of mass destruction?

Peter Bergen, recently wrote the following in an analytical piece for CNN, and it tends to cut through PC notions about a peaceful philosophy somehow turned on its head:

ISIS may be a perversion of Islam, but Islamic it is, just as Christian beliefs about the sanctity of the unborn child explain why some Christian fundamentalists attack abortion clinics and doctors. But, of course, murderous Christian fundamentalists are not killing many thousands of civilians a year. More than 80% of the world’s terrorist attacks take place in five Muslim-majority countries — Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan and Syria — and are largely carried out by groups with Islamist beliefs.

The Taliban and other Islamist terrorist groups are not, of course, secular organizations. To treat them as if they were springs from some combination of wishful thinking, PC gone crazy and a failure to accept, in an increasingly secularized era, that some will kill in the name of their god, an all-too-common phenomenon across human history.

Indeed, while ISIS and like-minded groups and their fellow travelers are not representative of the vast majority of the world’s Muslims, their ideology is rooted in Salafist ultra-fundamentalist interpretations of Islam, and indeed they can point to verses in the Quran that can be interpreted to support their worldview.

A well-known verse in the Quran commands Muslims to “fight and slay the nonbelievers wherever you find them, seize them, beleaguer them, “and lie in wait for them in every stratagem [of war].” When bin Laden made a formal declaration of war against “the Jews and the Crusaders” in 1998, he cited this Quranic verse at the beginning of his declaration.

ISIS’ distinctive black flags are a reference to a supposed saying of the Prophet Mohammed that “If you see the black banners coming from the direction of Khorasan then go to them, even if you have to crawl, because among them will be Allah’s Caliph the Mahdi.

In other words, coming out of Khorasan, an area that now encompasses Afghanistan, will come an army that includes the Mahdi, the Islamic savior of the world. The parent organization of ISIS was al Qaeda, which, of course, was headquartered in Afghanistan at the time of the 9/11 attacks.

Last year, ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi named himself caliph, which means that in his own mind and in the eyes of his followers he is not only the leader of ISIS but the overall leader of Muslims everywhere.

These beliefs may seem like a crazy delusion to most of us, but it’s important to understand that they are theological in nature, and this theology is rooted in ultra-fundamentalist Islam.

ISIS sees itself as the vanguard army that is bringing back true Islam to the world. This project is of such cosmic importance that they will break any number of eggs to make this omelet, which accounts for the’ir murderous campaign against every ethnic group, religious group and nationality that they perceive as standing in their way. ISIS recruits also believe that we are in the end times, and they are best understood as members of an Islamist apocalyptic death cult.

IS THERE ANY ROOM FOR DEBATE OR DIALOGUE?

Getting back to the literary festival of 2014. While there, I moderated two sessions, ‘Reading the Soul’ and ‘Writing the Self.’ The former was about how religious texts have their own literary tradition on the notebook of humankind; the latter was about the relative truth of memoir – in this case as told by two very different Bangladeshi-origin female authors, both of them Muslims.

It was difficult to avoid religion in both sessions, especially as one of the authors had chosen to read a passage from her book recounting an incident passed down from her grandmother in which she was humiliated by her Hindu teacher at school because he had forgotten to return her school notebook. The story culminated in the teacher ‘purifying’ his house by spreading cow dung on every surface. I was skeptical of her grandmother’s recollections – after all, as a student, how could she know he did this at his home without her having seen it? And, I wondered aloud why she had chosen to read that passage at the venue when her book had many more interesting passages. I saw behind her words something I’d observed in the ordinary cab-driver, the rickshaw-wallah, tea-seller – a bill of goods being sold in Bangladesh of historicn and continuing Hindu oppression that simply isn’t present in the place. It was then that I likened the Hindus of Bangladesh to the Jews in Nazi Germany. Their purpose is to be scapegoats. And, their right to live is less than the rest their citizenry.

My suspicions were confirmed as I met Hindus – one at the hotel, another who showed my wife and me around the Dhaka Kali Bari, even people at the Ramakrishna Math where they provide free education to mainly Muslim students – all of them told a similar story of insult, intimidation, threats. Tears streamed down their cheeks as they lamented the downfall of the secular state that they fought for in 1971, leaving them in a Bengali-speaking mini-Pakistan. They hadn’t bargained for this – but where could they go?

Later, I interviewed author and politician Shashi Tharoor for a video series for the organizers that was to be called Hay Festival Dhaka: Afterword, Afterwards – this, after Tharoor’s anchoring session at the end of the festival. During the discussion I asked him about the importance of having a sense of humour about one’s religion – and, indeed, without it, wouldn’t his novel, then celebrating 25 years in print, The Great Indian Novel have been banned? An engaging discussion ensued about a growing environment of competitive intolerance in the world. The organizers, I noticed, began to close in. People in the studio room were getting restless. Perhaps the discussion had hit a chord. Too much talk of religious intolerance.

I was never asked back to Dhaka. Perhaps, I poked and prodded in too many soft places. In the end, it’s likely a good thing in retrospect, for not one month after the festival was over, the first of the blogger killings occurred. When my wife read me the report of it in the newspaper, she was white as a ghost. ‘You can’t say the things you do in places like that,’ she warned. ‘We can never go back there for such an occasion, you know!’

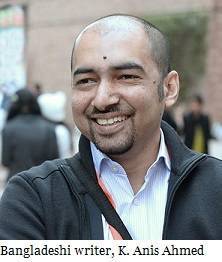

I was reminded of the experience again around the new year when I read a piece published online in the Guardian by one of the festival directors, author and businessman, K. Anis Ahmed. In it, he wrote about what cannot be written (or by extension spoken of) in the new Bangladesh:

“Things we don’t write about: The Prophet. The Quran. The mosque. The hijab. Indeed, anything to do with Islam that might offend anyone willing to kill. The problem is that we can never be certain what will offend them. The killing types are no longer visible, wizened old men who regularly announce where the red line lays. The mantle has passed onto teenagers wielding machetes, belonging to secret cliques, guided by international ideologies with vicious local consequences,” writes Ahmed.

By the end of his elegantly elucidated piece, Ahmed concludes that independence is something that “may have to be” be fought for over and over again. But he falls short saying that it must be – or that he will be doing so. Moreover, there is no attempt to argue the pen being mightier than the sword. Absent too is any mention that these things need to be discussed and the battle of ideas should be taken to the public airwaves – and not on the streets. Other than a mild resentment at being called to address these questions by less enlightened folk, I didn’t get the sense of his feeling compelled to lead a deeper discussion, especially as an influential new voice in Bangladesh. That vagueness, the somewhat mealy-mouthed safety measure conclusion, however sprinkled with defiance and peppered with optimism, left me dispirited.

I shouldn’t be surprised. Most Indian writers are no better when it comes to critiquing Islamic extremism. Ahmed by comparison sounds downright resolute. I give him credit for at least writing that these topics are taboo in Bangladesh – and they shouldn’t be. That’s something, at least. An Indian writer would be apt to say, “one cannot offend the minority sentiment…blah…blah…blah.” The kind of letter the censorship lobby sent to Rajiv Gandhi when they wanted Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses to be banned. So, I put Ahmed above any Indian writer in the courage category on that score.

I shouldn’t be surprised. Most Indian writers are no better when it comes to critiquing Islamic extremism. Ahmed by comparison sounds downright resolute. I give him credit for at least writing that these topics are taboo in Bangladesh – and they shouldn’t be. That’s something, at least. An Indian writer would be apt to say, “one cannot offend the minority sentiment…blah…blah…blah.” The kind of letter the censorship lobby sent to Rajiv Gandhi when they wanted Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses to be banned. So, I put Ahmed above any Indian writer in the courage category on that score.

In the final analysis, if more people opened their mouths, loosed ink from their pens or rattled on their keyboards, Bangladesh (maybe even the whole subcontinent) could have a soul-searching internal discussion on these critically important matters. In fact, the problem with the so called Muslim world (and I include India in this category) is exactly what Ahmed described – the cone of silence that threatens to calcify literary or intellectual thought. The fear that solidifies around people has overcome much of the subversive spirit of young writers. And that’s a shame, for without the confidence and moral authority of their voices – strong voices from within the culture – the killings will only continue.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine