Durga Puja Inc. and ‘The Company Puja’

“The socially significant Barowari Pujas, which were established so the public dare not depend on the benevolence of the wealthy have devolved into mere corporate events, the community, transformed into event managers, the public reduced to the role of gawker, tourists in their own land. This is the impact of Durga Puja Inc.”

The first in this series on Calcutta is available at the following link: Ghosts of Calcutta

Ghosts of Calcutta II: Durga Puja Inc. and the Company Puja

By SB Veda

CALCUTTA – The twelve rebellious men who started the first community or ‘Barowari’ (of 12 friends) celebration of Durga Puja, put together from meagre donations at a time when Calcutta’s Bahadur princes were showcasing their wealth and power, could scarcely have predicted that their tradition would escalate and become one of the most gratuitous displays of excess in modern India. But, there it is – this is Sharad Utsav: Durga Puja secularized and corporatized as Autumn Festival in Kolkata; its meaning lost on crowds snapping pictures, blowing noise-makers, eating drinking and making merry.

The display might best be called Durga Puja Inc., a seasonal spectacle around which an economy has been built – not unlike Mardis Gras in New Orleans or Carnival in Rio de Janeiro. From artisans to builders to bamboo salesman, caterers, restaurants, shops of all kinds – saris in particular, all benefiting from this boom period. Residents must pay a Puja bonus – an entire month’s extra salary, no less- all to fund the consumption down the economic food chain. This certainly puts the all but antiquated Christmas bonus in North America to shame. But then, Christmas, as commercial an occasion as it has become, is dwarfed by Durga Puja Inc. when one considers the relative buying power of Calcuttans compared to their counterparts in Western cities. Sharad Ustav’s consumption is proportionately far more gluttonous.

The fountainhead of this excess is the modern Puja Pandal, often an elaborate structure bearing expensive adornments, no longer limited to the makeshift tableau at which rituals are to be performed. A mere Pratima depicting the deities is insufficient, for these are not places of mere worship. Durga Puja Inc. is the spawn of a pageant and a temple, and this too on steroids.

Two years ago, the Times of India reported that total expenditures on Puja Pandals by the some four thousand local clubs of Kolkata, many of them collecting money through goons and politicians (sometimes they are one and the same) totaled 123 Crores of Rupees or around twenty five million dollars.

With scandalous ‘chit’ funds or Ponzi schemes being a conspicuous source of this funding, budgets for Pandals have been forced to come down, according to the press. Still, reports of modesty are greatly exaggerated.

The streets of Calcutta are littered with corporate logos, many of them displayed on huge bamboo archways vaulting the streets: An Indian Idol stall, sits humming a few feet from the Pandal in my neighbourhood while people are abuzz about another ‘Indian idol’ – a statue of the Goddess Durga, decked out in Rs. 10 Crores (around $2M dollars) worth of diamonds. Another Pandal garnering attention is crafted in gold sponsored by the jewellery franchise owned and operated by corporate giant, Tata Sons Ltd.

Many streets are closed by the Pandals, bringing Calcutta’s considerable traffic, never very fluid at the best of times, to a grinding halt. The social clubs either have the authority or audacity to dig up roads, penetrating pavement at times with jackhammers to plant the bamboo frames for their massive Pandal stuctures. The city, presumably, foots the bill for their repair – or else the roads stay potholed.

The same kitchy festival lights line the streets from year to year, though this does not mean to say that there aren’t variations in the kitch: not far from my flat, one club has erected a dwarf Eiffel Tower in white light over an intersection. It draws crowds – people with cellphone cameras in hand, flashes ablaze; they seem pleased that Durga Puja Inc. has brought The City of Lights to The City of Joy, never likely to gaze upon the real thing in their lifetime.

Before the advent of corporate sponsorship, power cuts were rampant, and generators were needed to keep lights on. These days, despite the additional demand for power, the lights stay on, courtesy of The Calcutta Electric Supply Company and their corporate peers. They are happy to ensure the festival goes off without a hitch. After all, what would the crowds do if it suddenly went black? Would the Marxists get their uprising?

It is quite evident to any observer that Durga Puja Inc. is a flourishing enterprise, drawing in millions of consumers who flock to the spectacles daily and nightly.

THE SHOBHABAZAR RAJBARI DURGA PUJA

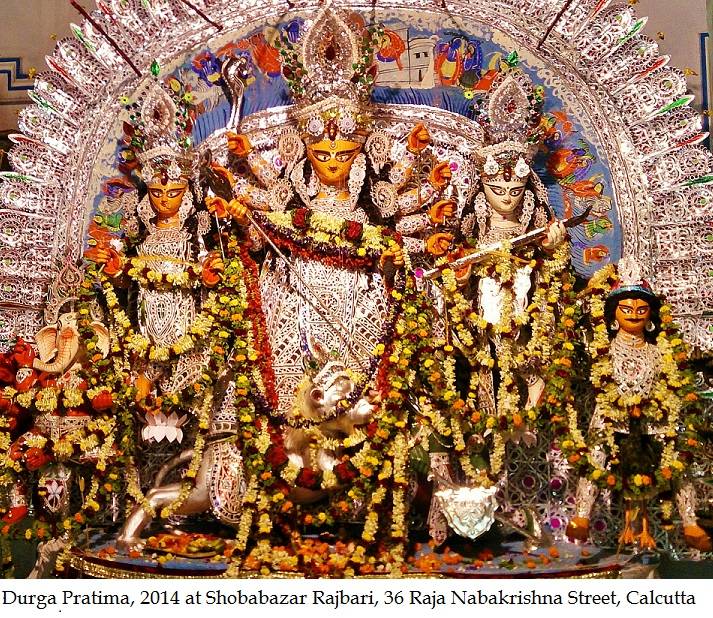

In an ironic twist of fate, perhaps the oldest Durga Puja celebration in Calcutta and certainly the most grand of the what many call the Great Old Houses of Calcutta – that of the merchant kings of Shobabazar Rajbari in North Calcutta, celebrated in the quadrangle of a palace built by Raja Nabakrishna Deb – seems modest, downright humble in comparison.

And yet, the Raja had hosted British major general, Lord Clive, at his palace, who having defeated the forces of Nawab Siraj Ud Daula, offered thanksgiving at the feet of the Goddess. Clive recognized the significance of routing the Nawab at Palashi (also known as The Battle of Plassy) in securing The British East India Company’s Indian assets, and wanted to give thanks but the only church in Calcutta at the time was razed to the ground when the city was sacked a year earlier by Ud Daula’s forces.

His tutor-secretary or Munshi (as termed in Farsi) Raja Nabakrishna Deb, already having obtained the title of Maharaja Bahadur from Warren Hastings, suggested he offer his thanks at Durga Puja to be held at his Rajbari.

‘But I’m a Chistian,’ Robert Clive is reported to have said. The pragmatic Raja promised that something could be ‘managed’. After all, pluralistic Hinduism purported that all paths led to the same goal. (This was before the Congress Party took credit for coming up with the idea of a secular India.)

The Deb family Puja, henceforth, kicked-off the season, announcing commencement with canon fire and their idols were the first to be immersed each year in the Ganga.

According to Jaya Chaliha and Bunny Gupta, two contributors to the historical anthology, Calcutta The Living City, Volume II (Oxford University Press) the British were entertained with dancing girls, and were permitted to dine as they pleased with food and drink being brought from nearby Wilsons Hotel, despite the conservative inclinations of their Hindu hosts – this was done surreptitiously, for surely the idea would offend orthodox Hindus.

Describing the occasion, Chaliha and Gupta write: “And so Clive came to Shobabazar in the Black Town (sic, native-inhabited Calcutta). A golden sofa was placed for him in the open quadrangle. The Durga Puja at 36 Raja Nabakrishna Street is still referred to as The Company Puja…which became a fashion and status symbol among the parvenu merchants.” (A quick note: this Puja actually took place at 33 Raja Nabakrishna Street, the original Rajbari. which was inherited by Gopimohun Deb, the Raja’s adopted son; 36 Nabakrishna Street was built after Nabakrishna Deb’s biological son, Radhakanta Deb was born some thirty years later.)

I do not see any golden sofa at the Burra (larger) Shobhazar Rajbari where I had been invited by the Deb family – absent too are European guests, though a ‘white’ tourist is taking pictures.

I do not see any golden sofa at the Burra (larger) Shobhazar Rajbari where I had been invited by the Deb family – absent too are European guests, though a ‘white’ tourist is taking pictures.

What I do see is a palatial colonial era property in decay, its size and architecture still evoking images of a bygone age – but lacking the upkeep to truly call a palace. Certainly, the cracked concrete and chipped paint in the front of the building are not indicative of the stately structure inside.

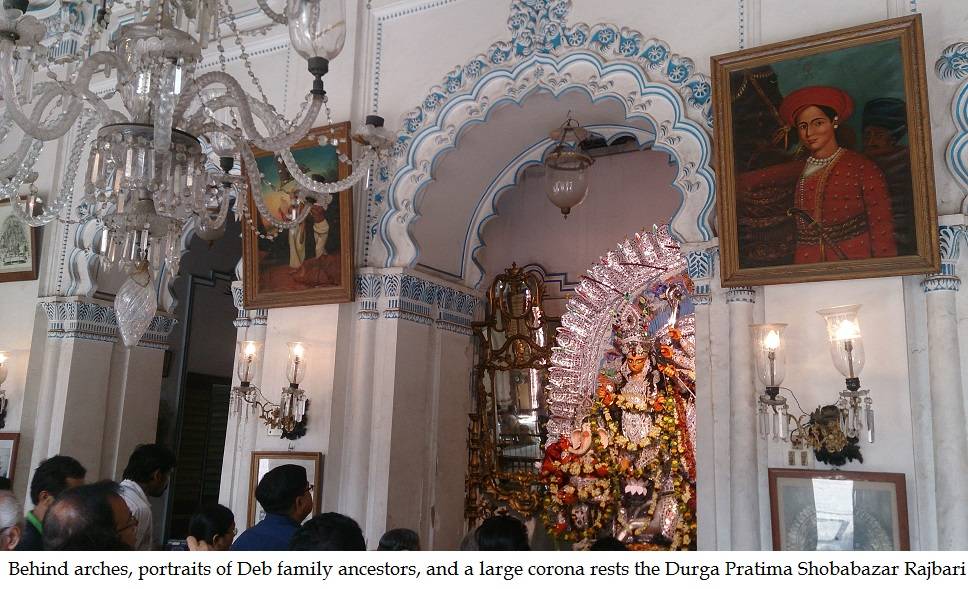

In an enclave adjacent to the quadrangle, behind ornate marble arches and portraits of the Deb family forefathers stands a large but modestly decorated Pratima, beautiful in its simplicity though noble in presentation, perhaps not unlike the idols of old.

A wooden rail protecting an area in front of the clay images where priests had sat earlier, keep worshippers at a distance. But not me, invited in as I am by the Deb family. For a short span, I feel like one of them, and sensing the spirits of the city within me, I am content, proud even to call myself a Calcuttan.

I am a prince for a day, celebrating among imaginary Rajas in a palace of illusions.

The city had long been associated with extreme poverty and filth by the Europeans and North Americans with whom I had mixed as a child and young adult, growing up in the West. I bore no small measure of shame to say that my extended family lived in this reviled place. The existence of such mansions, the Rajbaris – the thriving commerce and trade that took place during the British Raj in Calcutta – these were facts unknown to me. Today, those memories are all but extinguished.

I glance at the assistants cutting fruits and other offerings, gathering the ingredients, ‘Jogar’ for the Puja much as my mother and her peers do each year for my father and other volunteer priests when they are called by the Bengali community in Ottawa, Canada to perform the ritual. The warmth of the atmosphere and casual comportment of occupants, help make the Rajbari feel like home.

I had moved to Calcutta a few years ago from Canada, and have been bombarded with the sights and sounds of Pandals, each year at this time, since. I had conspired with my weaker self to give the Puja a miss, this year, hoping to escape to the hills to work on my book but my wife and son objected. How could one imagine leaving the city during Pujo? Is this not a time for family?

For me, Pujo was always a time for reflection but amidst the crowds, the noise and the general chaos, my thoughts are reactive rather than introspective during the festive season of modern Calcutta.

For me, Pujo was always a time for reflection but amidst the crowds, the noise and the general chaos, my thoughts are reactive rather than introspective during the festive season of modern Calcutta.

The festivities being timed around Canadian thanksgiving and university ‘homecoming’, Durga Puja in Canada offered the opportunity to reconnect with friends and family. Non-Bengalis observing Navaratri and Dussehra would invite us to their celebrations and Bengalis reciprocated. A borderless existence offered Hindus the opportunity for cultural integration.

At Shobabazar Rajpari, it is the first time during the Puja season at Calcutta that I find I can sit quietly in a familial atmosphere and do something I hadn’t done in a while – reflect, meditate even. I become lost in my thoughts insulated from the city by the Deb family’s home.

I am charmed by the graciousness of my hosts, especially Tirthankar Krishna Deb and his uncle, Aloke Krishna Deb, scions of a class of urban noblemen whose founder Nabakrishna Deb advised both Warren Hastings and Lord Clive, and facilitated the fall of the Mughal hold over Bengal.

Renowned Sociologist, Benoy Ghosh referred to the Shobhabazar Rajbari Debs as among the most celebrated and powerful of the Raj era Zamindars. They held title to lands both in the North East and Bengal, including some property in present day Bangladesh, and significantly, nearly all of Sutanati, one of three villages, which The British East India Company amalgamated into Calcutta.

Family head Aloke Krishna Deb says he needs a museum with a library to adequately preserve all the documents regarding the large family’s history and their assets. Among them would be the deed to Sutanati, which was the centre of the textile industry in Calcutta.

The name of the neighbourhood derives from Shobaram Basak, the textile king of Calcutta, and a thriving textile bazar was situated there. A smaller market or hut still operates in the neighbourhood. Raja Nabakrishna deb is said to have bought the first Rajbari from Basak, and expanded it into a palace.

The Deb family, like other Zamindars were close to the British but unlike many of their ilk whose activities were mainly limited to trade with The British East India Company, taking up lucrative and influential posts, the Debs were active in the cultural and intellectual life of the city. Raja Nabakrishna Deb is known to have cultivated a large assembly of scholars and religious men at his court, “inviting some of the finest intellects from the traditional centres of learning at Shantipur and Nabadwip,” writes scholar, Chitra Deb.

While Nabakrishna had been a patron of scholarship, Radhakanta Deb was a scholar and writer, himself. He was also a publisher. “His greatest feat was the publication of the Sanskrit encyclopaedia, Shabdakapadruma in eight volumes over half a century at a cost of sixteen lakh rupees, from a press set up in his own house,” writes Chitra Deb. The publication cost alone would be roughly $600,000 in present day funds (around 3.5 Crores of Rupees). She adds, “He published his Bengali textbook, Shikshagrantha in 1821, and brought out Gourmohan Diyalankar’s book on female education, Streeshikshabidhayak, the same year…he also composed a book, Vedanta: What it is.”

A ‘BARIR’ PUJA

Aloke Krishna Deb with in front of the Durga Pratima at Burra Shobabazar Rajbari

The head of the family, a fit grinning white haired man, full of energy, Aloke Krishna Deb tells me to be at ease, that his family tradition is to treat their guests like living Gods, so they open their doors for the occasion each year.

Ordinary people stroll in an out of the palace; many are lined up for a meal of Bhog, offerings made to the Goddess. It is busy but not jammed like the Pandals. Well, I suppose if you’re a Pandal hopper there is nothing novel to glean, here. It is an occasion better suited to the devotee both of Ma Durga and of history.

Still, they had their time, the Debs of Shobavazar: The ostentatious nature of their festival was legendary, even around independence.

‘Just before 1947,’ says Aloke Krishna Deb, ‘when I was a boy, I remember around a hundred soldiers from the Scottish Highlands were brought in to play bagpipes for us,’

The pendulum has swung away: time, the abolition of Zamindari, and a famously stunting Raj era bureaucracy has denied them their wealth. Much of it lies in trust, and held by the High Court, Calcutta due to an inheritance dispute.

Mr. Deb is a retired Civil Servant; absent is the arrogance that often comes with massive means, ‘We are kings in name only,’ he says. ‘But we have upheld the traditions of our ancestors – only the quantity (of celebration) is less.’

He bounds with youthful vigour from one end of the quadrangle to another, taking care of this arrangement, that detail, talking to a stray person. His booming voice is a result of hearing loss but this seems to be the only diminishing distinction of age. Nearing eighty, he attributes his good health and energy to his devotion to the family deity, Gopinath Jiu, who resides on the first floor of their home. His ancestors, the Radhakanta line of succession, accepted a less valuable inheritance than those of Gopimohun Deb’s family because the lesser lands came with their beloved idol. Flush with wealth and power, in the end, Radhakanta’s devotion to the deity was what he held most dear. This devotion has flowed down nearly twenty generations, and it has kept them modest in the process.

“We are simple people,’ he says, “and we are conservative as shown by our dress and manner.” He wears a white cotton Kurta Pajama, his hands absent the bulky rings that can be seen weighing down the fingers of his counterparts in Bengali society – both old and new; there is no gold chain around his neck. It is as though he knows these trinkets however valuable, are instruments of bondage, and flits freely unencumbered by them.

The members of this formerly majestic family, still proud of their storied past, exhibit a humility that exists in stark contrast to the increasingly consumeristic pastime of new Kolkata – showing off.

TWO DEMONS

The irony of Calcutta’s Pandal culture is thick and hangs over the city like the smog above the incense for those who are aware of the meaning behind the ritual.

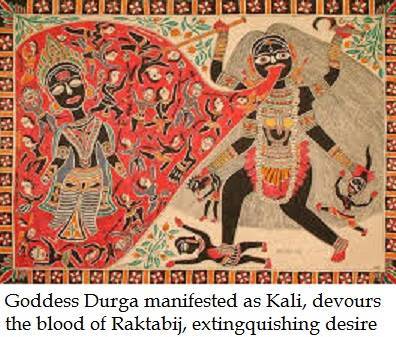

Legend has it that two demons were vanquished by The Goddes Durga and her other manifestation, Kali as described in the ancient Upanishad scriptures, the Devi Puranas. Durga Puja celebrates the triumph over one – Mahisashura, Kali Puja – victory over the other – Raktabija.

Thousands of years after the legend became known, these demons seem to have reincarnated in the Pandal culture of modern Kolkata.

According to scripture, Mahisasura’s father, Rambha, a demon king, had fallen madly in love with Mahishi, an Asura who could transform into a buffalo at will, at times maintaining hybrid form. He took her as his wife – and while with child, she was abducted by an ex-lover from her abode. The two fought; Rambha was killed.

Devastated, a grieving Mahishi leapt on to Rambha’s funeral pyre – an act which moved Lord Yama, God of Death. He halted the migration of Rambha’s soul, and redirected it into Mahishi’s womb. Out of the cremation fire emerged twins: Mahishasura, the son conceived of Rambha and Mahishi; and Raktabija, the reincarnated Rambha.

Mahishasura was a great soldier and his penances garnered him a boon from Lord Brahma. Arrogance would be his undoing: he asked to be impervious from death by either man or god, for surely he had nothing to fear from a mere woman.

Raktabija had also gained a special power: wherever his blood would fall, his seed would sprout, and he would be duplicated.

The demon army led by these twins were terrorizing the known worlds. So, the Devas (Demi-Gods) appealed to the holy trinity Brahma, the Creator, Vishnu, the Preserver, and Shiva, the destroyer to eliminate the threat. Together, they created the ten armed Goddess, Durga. They, along with the Devas armed and empowered her. In turn, she manifested their combined power.

Unprotected from being killed by a female and underestimating the female he faced in battle, Mahishasura proposed marriage to Durga when he met her on the battlefield. He is ego personified, and she was enraged at his arrogance. In killing him, Durga demonstrates that we must conquer our ego on the path to enlightenment.

Similarly, Raktabij represents desire for which there is no end to satisfaction – one drop of blood begetting another demon, one craving satiated giving rise to another one. Durga, assuming the form of Kali, cut his head off and drank his blood: her solution being to eliminate all desire.

Similarly, Raktabij represents desire for which there is no end to satisfaction – one drop of blood begetting another demon, one craving satiated giving rise to another one. Durga, assuming the form of Kali, cut his head off and drank his blood: her solution being to eliminate all desire.

****

THE BANE OF THE BAROWARIS

Those twelve friends, the Barowaris from Hugli, who in 1790 started the first community Puja, were they alive today, might be aghast at their successors, who are part of a system that celebrates some of the ideals, which they sought to oppose.

The Puja celebrations of social clubs have become theme-based. Through their Pandals, they project their creativity, inventiveness, and wealth. ‘Look at what we’ve created,’ they cry out, ‘our Pandal is the best!’ However substantial their achievements are to be judged, theirs is also ego personified – celebrated, in fact.

The system of corporate sponsorship and reward has created an unending demand for the Pandal culture. Today, one’s Pandal is only as good as the prizes it has won in the current year. It leaves an unending need to outdo efforts of prior years, and this too is fueled by corporate sponsorship. Durga Puja Inc. knows the prize-winning Pujas will draw in more crowds – more potential customers to whom they can pitch their wares. This is desire, multiplying ceaselessly from year to year.

Aside from a modest poster from the Times of India, the corporates are absent from Shobabazar Rajbari. It is a time for family members to connect with the public, who are treated as guests rather than consumers.

Asked about the Pandal culture, Aloke Krishna Deb is ambivalent, ‘Theme-based Pujas are what they are – I don’t want to criticize them but that is not Puja. That is all pomp and grandeur. I have no quarrel with them. Let them enjoy.”

Presumably his family also enjoyed, I suggest, having read about the famed pageantry of their house. Concurring, he volunteers to elaborate, ‘Yes. In fact, I have seen a lot of pomp and grandeur since I was a boy at our home – dance, theatre, Kobi-loray (poetry recitation competitions). We used to start our Puja with the firing of a canon! I have seen all this – but we always followed the rituals seriously, being conservative Hindus: there was no surrender on this matter. Now, there is no more pomp and grandeur but we are still following the rituals with utmost dedication.’

He adds: ‘Ours is a Barir Puja (House Puja) – that is to say, we follow all the rituals, and that is our focus. Every year, we welcome the Goddess as a daughter returning to her father’s home – and we do so with love.’

Kolkata, it appears, has turned Calcutta on its head. The socially significant Barowari Pujas, which were established so the public dare not depend on the benevolence of the wealthy have devolved into mere corporate events, the community, transformed into event managers, the public reduced to the role of gawker, tourists in their own land. This is the impact of Durga Puja Inc. At the same time, the Shobabazar Rajbari Puja, no longer The Company Puja for the presence of the British, has become a simple Barir Puja – a conclusion, which by comparison is far more awe-inspiring than the palace walls that house it.

Somewhere, Raja Nabakrishna Deb is smiling, and the ghosts of Calcutta smile with him.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine