Game of Combs: Is Boris the New ‘Mad King’

“Lannister, Targaryen, Baratheon, Stark, Tyrell they’re all just spokes on a wheel. This ones on top, then that ones on top and on and on it spins crushing those on the ground….I’m not going to stop the wheel. I’m going to break the wheel”- Daenerys “Stormborn” Targaryan, GRR Martin’s fictional Dragon Queen.

HBO’s popular TV series, Game of Thrones based on novelist GRR stories, begins some two decades after a mad king’s throne is usurped in a rebellion by a popular warrior-lord. The rebellion is considered just, and the harbinger of doom, Aeris Targaryan who would sooner see his capital burn with all its people than compromise or yield to any demands of the rebels.

In a long and winding plot to regain the kingdom, the Mad King Aerys’ daughter, the Dragon Queen, Daenerys Targaryen finds herself in the position of reclaiming a throne that she sees is righty hers. Having raised a formidable army and defeated a common enemy, the capital is about to fall. The bells of King’s Landing ring for surrender. The gates to the city are about to swing open to welcome the new conqueror – and then, she decides in a fit of rage (and simply because she can) to raze the city to the ground, kill all those who dared not question the regime that defeated her family. Her fire-breathing dragon (the equivalent of a nuclear weapon) kills almost everyone, and the scenes of the aftermath show snows falling like nuclear winter.

Why does she do it? Clearly it was a fit of madness but she reflects that she is breaking the wheel. She feels one must destroy the system in order to create a new order – one independent of elite lords – a just system that serves the people.

On the surface, she seems to want a kind of representative democracy. And, following her ultimate betrayal by her inner circle, a form of democracy – the vote of the elites – replaces the autocracy of the ruler. The conspirators have lingering doubts about their actions. Would she have made the fictional Westeros a better place, for she was single-minded in believing in her own greatness and in destiny. And, she had a dragon. So, what would have happened had she not been murdered by her most loyal supporter, Jon Snow? One can only speculate.

Could London’s metaphorical fate be akin to that of fictional King’s Landing after the Dragon Queen razed it to the ground?

What we didn’t know is that in 2016, Brexit was the Dragon Queen that razed professional politics to the ground. It wasn’t always so. For his seminal lecture on “The Profession and Vocation of Politics” the acclaimed sociologist, Max Weber, delivered in the anarchistic aftermath of the First World War, lauded the British system for the way its politicians and officials managed to preserve economic and political stability while enabling a democracy to function.

Seemingly, it is still so. An unpopular leader steps down in the form of Theresa May and her successor, now more popular than ever – but this too, only in his own party, Boris Johnson succeeds her, assuming the mantle of Her Majesty’s first minister in governing a kingdom that unites four countries.

If we were to follow Weber’s thesis –that professionalism governs British politics, then Brexit would have polarized politicians into two camps – but it hasn’t. The reason lies in the abandonment of principle in British (indeed, global) politics. Theresa May had campaigned to remain in the EU. As a compromise candidate, many Remainers felt May would be able to bridge a compromise between the rest of the EU and Britain so the country could continue to gain benefits from the common market, thereby staying economically afloat.

Instead, May made an abrupt about-face. Intent on winning over hardline Leavers such as Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, powerful rivals, she took a hardline on Europe. In the end, the deal she negotiated could not be stomached by those who had supported her leadership.

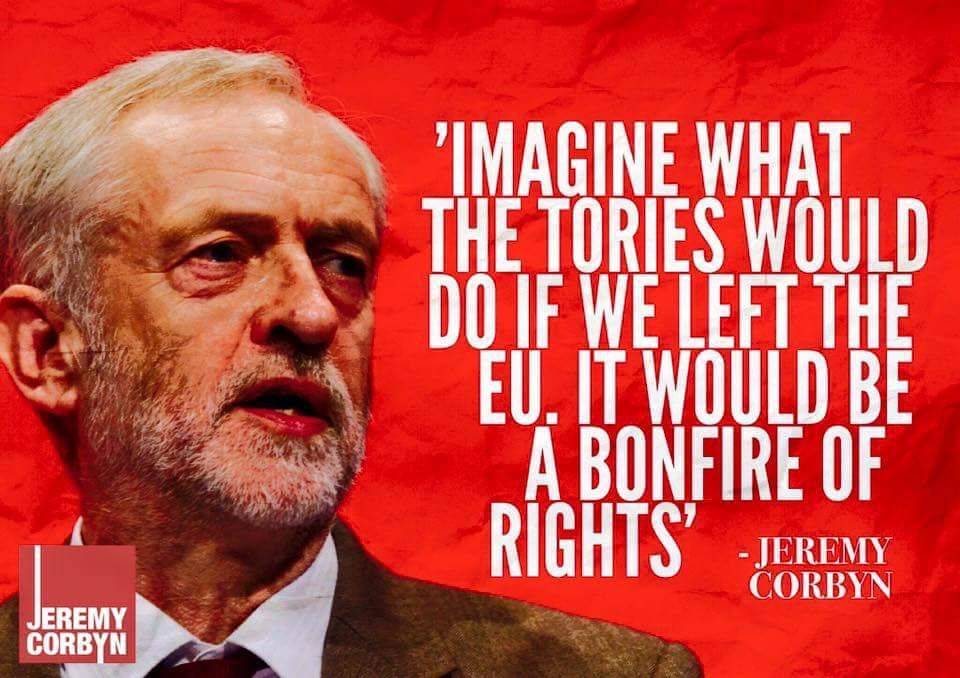

Similarly, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, whose career has seen outright hostility to Europe (calling him a Euro-skeptic would be like saying Hitler was somewhat hostile to Jews). Corbyn also campaign for the Remain camp – but with all the enthusiasm of a wet noodle. Corbyn is a closet leaver, and his party, the majority of which are either Remainers or favour a second referendum on the question of the EU, failed to oust him in the aftermath of Brexit – and seem to be sitting on their hands.

The result has been defections from the Conservatives and Labour to smaller parties that have coalesced around specific issues: The Green Party around the environment; The Scottish National Party (who see the Brexit vote as an existential boost for Scottish independence given they voted in all consistencies to keep faith with Europe); The Liberal Democrats (Their anti-Brexit stand is sincerely championed by their leader, Jo Swinson, unlike Jeremy Corbyn’s surreptitious support o Brexit while officially holding the anti-Brexit party line of Labour); The Democratic Unionist Party (now allied with Johnson but holding his feet to the fire on Brexit); Sin Fein, a left wing Irish republican party, which supports staying in the EU and keeping the Northern Ireland/Irish Republic border a porous one; Change UK, which has attracted both labour and conservative MPs with strong views on remaining in the EU to put aside their political differences in the name of shaping Britain’s place in the world; And, these are just a handful of parties that have been birthed by lack of principle among the Conservatives and Labour.

Boris Johnson said very little of substance in his maiden speech as Conservative Party leader. The one thing he made clear is that on Halloween, Britain’s relationship with Europe will be a ghost, deal or no deal. And, this, he said, was most democratic.

Johnson has installed hardline Leavers in key posts in his new cabinet and exiled to political Siberia, those who stood for a second referendum.

Like Daenerys, Boris believes in his own manifest destiny. This is the man who, as a boy, wanted to become “world king,” and whose ambition has been so obvious that it rubbed off on everybody else. Since 2001, when Johnson first became a Member of Parliament—he was editing The Spectator, a right-wing political magazine, on the side—the outrageous possibility that he would become Prime Minister one day has been talked about so often, and with such happy disbelief, that it is hard to identify the moment when incredulity turned into expectation

Even when people have despised Johnson, his actions—whether as the mayor of London, campaigning for Brexit, writing a biography of Churchill, or messing about as Foreign Secretary—have always been framed as part of his ambition to rule the country. His political career has not consisted of doing politics in any ordinary sense. It has all been preparation. Johnson himself has spoken of “this cursus honorum, this ladder of things” that he has felt compelled to climb throughout his life. Now he is at the top, with nowhere else to go.

As regards Brussels, thought, his opposition to the bureaucrats of the place run deeper than an effort to cut red tape: Sam Knight of the Neworker writes that Brussels was a deeply unhappy place for Johnson growing up as a child, and this was confirmed by his siblings.

It is hard not to discern a psychological motive in Johnson’s assault on the E.U. machine. As his siblings have pointed out, Brussels had been a deeply unhappy place for him as a child. The Johnsons had lived in a big house in the suburbs, next to a forest. According to Purnell, Rachel Johnson, Boris’s younger sister and also a prominent journalist, has compared life at the time to “The Ice Storm,” the Rick Moody novel about a disintegrating family. “There was the same bleakness, the disconnection,” she has said. Stanley had affairs, and the marriage slowly fell apart. When Johnson was ten, his mother, Charlotte, suffered a breakdown and was hospitalized for nine months. Boris and Rachel were sent to boarding school. When Johnson came back to Brussels, he had a wife, Allegra Mostyn-Owen, whom he had met at Oxford. The couple lived in an unprepossessing apartment above a dentist named Goris. Johnson disappeared into his work at the Telegraph. “I used to get the paper—yesterday’s news—and there’s his byline in fucking Zagreb,” Mostyn-Owen later recalled. “You get past caring and you start drinking malt whisky.” Mostyn-Owen feared that she would crack up, as Johnson’s mother had. (The couple divorced in 1992; Johnson married his second wife, Marina Wheeler, whom he had known as a child in Brussels, twelve days later.) In the Telegraph’soffices, which overlooked an elegant square, Johnson would lock his door and shout obscenities to himself, while he worked himself up to write each story. “This bizarre ritual, to those who witnessed it, was an insight into the torrent of focus and drive that lies beneath Boris’s affable exterior,” Purnell writes.

In 1994, Johnson was recalled to become the Telegraph’s chief political columnist. He was a newspaper star. But his reporting was no longer credible. “He was by then a caricature, and he had to go,” James Landale, then a reporter at the Times of London, who is now the BBC’s diplomatic correspondent, told Purnell. To mark Johnson’s departure from Brussels, Landale wrote a poem, based on Hilaire Belloc’s “Matilda,” in which “Boris told such dreadful lies / It made one gasp and stretch one’s eyes.” When Johnson returned to London, he confessed to an editorial writer at the Telegraph that he had no political opinions. “You must have some,” the colleague reassured him. “Well, I’m against Europe and against capital punishment,” Johnson said. “I’m sure you’ll make something out of that,” came the reply.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Johnson is not as English as he seems. He was born in New York. His electric-blond hair is an inheritance from his great-grandfather Ali Kemal, an outspoken journalist from northwest Turkey, who served as Interior Minister in the last days of the Ottoman Empire. In 1909, Kemal’s first wife, Winifred Johnson, died in childbirth in England, leaving two children to be raised by her mother. Johnson’s grandfather Osman, who was known as Wilfred, left school at thirteen and went to seek his fortune as a farmer in Egypt. During the Second World War, Wilfred flew for the Royal Air Force. According to family lore, he crashed a plane while trying to do a trick for his wife, a minor European aristocrat named Irène Williams, who was watching from the ground. Wilfred was badly hurt. “This was later spoken of by the family as a great joke,” Gimson writes. (Stanley Johnson clarified that his father crashed after an engine on the aircraft fell off and that Wilfred received a medal for skillful flying and avoiding casualties.)

Boris Johnson’s upbringing was privileged but contingent. Stanley moved jobs. His mother was fragile. It was important to win but vulgar to prepare. Performing plays at Eton, Johnson delighted the other boys by forgetting his lines. Once, when playing Shakespeare’s Richard III, he pasted pages of the script to pillars in the school’s cloisters and spent the performance running between them. He was slapdash and constantly late, and awaited a great future. “I think he honestly believes it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception, one who should be free of the network of obligation which binds everyone else,” Johnson’s housemaster, Martin Hammond, wrote in the spring of 1982, when Johnson was seventeen. Despite his fecklessness, Johnson expected to be made the Captain of School, the head of the scholars’ house at Eton, and duly was. He looked the part. He sang the hymns. “In an odd way, he likes an ordered world, not a random world,” Hammond told Gimson. “Boris was not a rebel at all. He was a fully signed up member of the tribe.”

It was the same at Oxford, where Johnson joined the Bullingdon Club, the university’s most exclusive all-male dining club, and sought the presidency of the Oxford Union, its debating society. Johnson was brilliant on his feet. Anything could be played for laughs. Johnson became the union president by pretending to support the Social Democratic Party, which was fashionable at the time, and switching to the Conservatives when he got the job. Frank Luntz, an American pollster, was a contemporary, and he warned Johnson not to do it. “This is a very small country and it’s not right,” Luntz said. “It will come back to haunt you.” But it didn’t, because—who cares? In 1988, Johnson contributed a chapter on student politics to “The Oxford Myth,” a book of essays edited by his sister, in which he emphasized the importance of cultivating adoring followers. “The terrible art of the candidate is to coddle the self-deception of the stooge,” Johnson wrote. In 2003, as an actual politician, Johnson disavowed this insight into his behavior as a young man: “I think my essay remains the locus classicus of the English genre of bogus self-deprecation.”

This is the Johnsonian way. The lies, the performative phrases, the layers of persona—they accrete, one on top of another, flecked here and there with Latin, until everyone has forgotten what the big deal was. In Brussels, Johnson confined himself to dodgy journalism. When he returned to London, he brought the same approach to jobs, extramarital affairs, and political stances. In 1999, Johnson became the editor of The Spectator, a witty, right-wing magazine that is traditionally close to the Conservative Party. The magazine was owned by the news magnate Conrad Black, who would call Johnson and ask him how it was going. Johnson would say that he was trying to turn the magazine into a cookie. “ ‘An opening of solid meal followed suddenly and dramatically by a chocolate taste explosion,’ ” Black recounted to Gimson. “It’s all rubbish, but it’s imaginative.”

In 2001, at the age of thirty-six, Johnson was elected a Member of Parliament for Henley, a safe Conservative seat in Oxfordshire. When he came under pressure to resign from The Spectator, because of the conflict of interest, he demurred, and coined what has become his best-known political aphorism: “I want to have my cake and eat it.” Johnson hates choosing between things, even right and wrong. In 2003, Lynn Barber, of the Observer, asked Johnson what principles he would be prepared to resign over. “I’m a bit of an optimist so it doesn’t tend to occur to me to resign,” he replied. “I tend to think of a way of Sellotaping everything together and quietly finding a way through, if I can.”

The Anglo-American alliance has never seemed more aligned with ‘BoDo’ but it begs the question, who will inherit the Iron Comb?

It is hard to predict how Johnson will respond to finally getting the thing that he wants. (In 2016, when he was the overwhelming early favorite to succeed David Cameron, he collapsed in prevarication and self-doubt.) But there are several things that we can safely say. The first is that, until now, Johnson has never been a very effective politician. In his most important executive role, as the mayor of London, Johnson did fine. Neither more nor less. He had no major policy agenda and, beyond a few vanity projects, he left the city basically untouched. Johnson is much more interested in having power than in doing anything with it. As Britain’s Foreign Secretary, between 2016 and 2018, he was in a position to work on the momentous job of leaving the E.U., a cause that he had championed for much of his working life. But he simply shambled about, making mistakes. “Cleaning after him was quite a full-time activity,” Alan Duncan, a junior minister who worked for Johnson, said last month. (Duncan has resigned, rather than serve in a Johnson government.)

Weber’s professional view of politics in the UK would have seen a new Prime Minister speak less in absolutes, offer hope of reconciliation, and attempt to broaden his tent. In the aftermath of Brexit, nonoe of this plays. That’s because Brexit was the dragon that burnt down the capital.

London no longer exists as part of England. Led by a liberal Muslim, it seems more a city-state than the capital of a country. The Kingdom is far from united. We have Scotland, which voted overwhelmingly to remain along with London and its boroughs, pockets of England and Wales (mainly university towns), Northern Island and Gibraltar being pitted against provincial England whose blue collar cockney accented football hooligans would rather live off the dole than compete for jobs with dirty Eastern Europeans.

Brexit, with the lies of the Leave campaign forming dragons breath, has burnt to a crisp England’s civility. And., Boris Johnson represents this. No…he is not a chav. Rather, a blue-blood Etonian who studied classics at Oxford, he has adopted Trumpian ways, sacrificing principle long ago for political expediency. Beginning with dog whistle politics, he now trumpets his bigoted tune – all with a smile on his face. “Don’t worry, be happy,” he implores people wherever he goes. It won’t be so bad, leaving Europe. Look at how great we are in gene therapy – and, after all, we survived the Battle of Britain – how bad could this be?

Oh…wait, didn’t he say it’s “do or die?” Dying would be pretty bad, wouldn’t it?

If Brexit was the Dragon Queen, what can help Britain rebuild its political edifice in the aftermath – and this too, before the deadline imposed of October 31st.

There is but one answer – another election. People must take to the streets, strike, sit-in, refuse to permit any activity to go forward until Boris Johnson calls another vote. For all the talk of breaking the wheel, Britain’s people neither voted for Theresa May nor for Boris Johnson. They are not Thatcher or Blair or even Cameron, for these leaders were elected by a fresh electoral mandate – not chosen by a small conservative elite. It’s time to give the UK an opportunity to regain credibility, civility, and above all stability.

700,000 protesters gather to demonstrate foe a 2nd Referendum on Brexit. It turned out to be the second largest such rally this century. Hence, strong mandate exists to defeat the government and force an election on the issue.

There is but one hope for the UK – to call an election. As markets have shown, today, Boris and Brexit didn’t break the wheel – they broke the pound.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine