John McCain Argues for an India Pivot in US Foreign Policy

“India and the United States must play a leading role, both together and with other like-minded states, to strengthen a rules-based international order and a favorable balance of power in Asia.”

The Pivot to India

Why the U.S.-Indian partnership is at the heart of America’s future in Asia.

By John McCain, United States Senate

The May election of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has transformational potential. Indians are hungry for bold change, and they gave a once-in-a-generation mandate to a leader eager to deliver it. This change is already extending to India’s foreign policy, including the strategic partnership between our countries. How to take full advantage of this unique moment will be the key question when Modi meets with President Barack Obama this week in Washington.

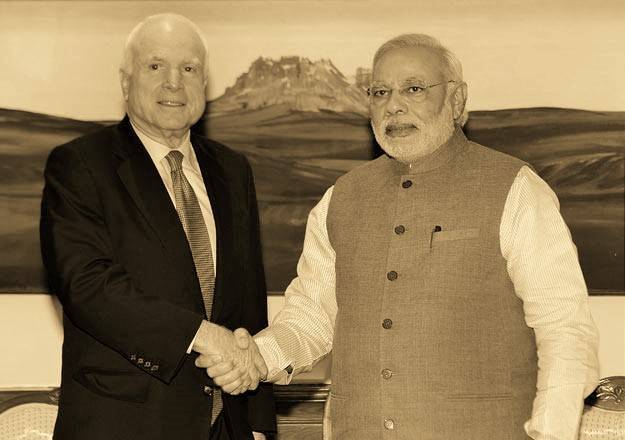

I met Modi in July, and my impression is that he sees a strategic partnership with the United States as integral to his goal of economically and geopolitically revitalizing India — and that India’s revitalization can, in turn, help reinvigorate our partnership. Modi and I agreed that this goal is much needed, because recently, our partnership has not lived up to its potential.

Too often, our relationship has felt like a laundry list of initiatives that amounts to no more than the sum of its parts. Too often, we have been overly driven by domestic politics and overly focused on extracting concessions from one another, rather than investing in one another’s success and defining priorities that can bring clarity and common purpose to our actions. Our strategic relationship has unfortunately devolved into a transactional one.

My sense is that Modi wants India to do its part to change this — and that he wants India and the United States to think bigger and do bigger things together once again. I fully agree. And to realize these ambitions, India and the United States first need to recall why we embarked on a strategic partnership in the first place. It was not for run-of-the-mill reasons. We affirmed that India and the United States, two democratic great powers, can and should lead the 21st century in sustaining a liberal, rules-based international order, supported by a favorable balance of power.

The benefits of this international order — which the United States has played an exceptional role in building, defending, and strengthening since World War II — are difficult to overstate for India and the United States. And yet, the global distribution of power is shifting substantially. We recognize that while U.S. leadership remains indispensable, we increasingly need willing and capable partners that share our interests and values to serve as fellow shareholders in the maintenance of our shared vision of international order. More than ever, we see a key role in this endeavor for a democratic great power like India.

An India-U.S. strategic partnership is possible, and indeed essential, because we share values as well as interests. This is what gives us confidence that India’s continued rise as a democratic great power will be peaceful, and that it can advance critical U.S. interests. This is why we seek not to curb the rise of India, but to catalyze it. And this is also why closer ties between India and the United States have consistently enjoyed broad bipartisan support in both countries.

It is worth recalling this original sense of purpose, because I fear we have lost much of it in recent years. And there is blame on both sides.

In Washington, there is a sense that the relationship has not met our admittedly high expectations. From trade disputes to setbacks in our civil nuclear agreement, there have been impediments and disappointments — compounded by several years of economic slowdown and political gridlock in Delhi. This is why Modi’s election can be such an opportunity: It’s a chance for India to rebuild its confidence and grow more ambitious and strategic in its relationship with the United States.

However, this depends on India’s confidence that a partnership with the United States is worth the investment. And I’m afraid some in India are starting to doubt.

Many Indians I have met worry that the United States seems distracted and unreliable, especially in its relations with India. They are concerned that Obama’s “pivot to Asia” seems more rhetoric than reality, in large part due to devastating cuts to U.S. defense capabilities under sequestration. They worry that U.S. disengagement from the Middle East has created a vacuum that extremism and terrorism are filling. They are concerned by perceptions of U.S. weakness in the face of Russian aggression and Chinese provocation. And most of all, they are concerned by Obama’s plan to withdraw from Afghanistan by 2017, which Indians believe will foster disorder and direct threats to India.

I am sympathetic to these concerns. Many of the administration’s policies are imposing costs on India, and potentially reducing the value of a partnership with America in Indian eyes. What do we do about this? How can we rebuild the strategic focus of our partnership? I would make two broad suggestions.

First, India and the United States need to think more ambitiously about investing in each other and improving our capacity to work together. The United States wants Modi to succeed because we want India to succeed. When India thinks of its partners in the world, we want it to think of the United States first — positioning our country as the preferred provider of the key inputs that can help to propel India’s rise.

The United States should be India’s preferred partner on energy. The United States is unlocking transformational new supplies of oil and natural gas, and India’s demand for both is rising.

It is in the U.S. interest for democratic partners like India to gain greater access to our energy, which can help them reduce their dependence on unstable or problematic energy suppliers. This will be difficult, and may require legislative changes, but the economic and strategic benefits would be immense.

We should also be India’s preferred partner for economic growth — spanning education, human capital and infrastructure development, and especially trade and investment. U.S. companies and capital are always looking for opportunities, and they will go where they find transparent governance, effective institutions, rule of law, and a favorable regulatory environment. In this way, Modi’s domestic reform agenda can help to attract greater U.S. trade and investment. And these U.S. ventures can, in turn, reinforce Modi’s domestic reform agenda.

Our governments are currently negotiating a bilateral investment treaty, which would establish terms to govern investment between our economies. This is worthwhile. But why not aim instead for a free trade agreement (FTA), which would remove all barriers to cooperation between our entire economies? India and the United States have, or are negotiating, FTAs with every other major global trading partner, so we are on course to discriminate only against one another. This makes no sense.

Our goal should be to produce a road map for concluding an FTA and to start negotiating it. We could then work toward India’s integration into the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a major international trade partnership, once it is finalized. Would this be extremely difficult? Of course. But the same was said of our civil nuclear agreement, and we did it.

We should be India’s preferred partner on defense issues as well. Our militaries must work to sustain a favorable balance of power in key parts of the world. This means building new habits of strategic consultation and cooperation, developing a common operating picture, and conducting joint exercises in all domains. It means the United States transferring technology to India that can make its defense acquisitions more effective, and India being able to protect these capabilities as U.S. law requires.

It also means joint development and production of leading-edge military systems, as envisioned in the Defense Trade and Technology Initiative (DTTI), which the U.S. and Indian governments launched together to further our co-development and co-production goals. The pilot program for DTTI is anti-tank missiles, which would be a good start. But when Modi and Obama meet this week, I hope they lay out more ambitious joint ventures, like shipbuilding and maritime capabilities, and even aircraft carriers.

These and other efforts to deepen our investments in each other can help to restore the strategic focus of our partnership. What should follow is an ambitious strategic agenda to shore up a rules-based international order that supports our common security and prosperity. This will require us to prioritize three areas of the world.

First, South Asia: Modi seems to correctly recognize that if fires keep breaking out close to home, that will hinder India’s global ambitions. This is another reason why a secure South Asia is in our interest, and why India and the United States must work together to achieve it. Most immediately, we should increase our counterterrorism cooperation and intelligence sharing. But ultimately, enduring security in South Asia depends on civilian-led democracy and an open regional trading order. These values create an alignment of interests among peoples across the region. Strengthening these supporters of a rules-based international order is the best way to weaken our opponents, especially violent extremists and their sponsors in Pakistan.

Another strategic priority should be the Middle East, where threats to our security, interests, and values have never been greater. Indeed, al Qaeda’s early September establishment of an affiliate in India is perhaps the clearest reminder of the vital stake that our nations have in a stable Middle East. This growing threat requires an evolution of thinking in New Delhi, which has often tended to look at the region as someone else’s problem. Hopefully, Obama and Modi can agree on a bold new direction of expanded cooperation — diplomatic, economic, and military. Imagine the signal India would send if it joined the international coalition to confront the Islamic State.

A final strategic priority is East Asia and the Pacific, where the key challenge to a liberal, rules-based international order comes more from strong states and growing geopolitical rivalries than weak states and nonstate actors, as in the Middle East.

The idea that Asia’s future will be determined by China or any one other country is wrong. Across this vast region, more people live under democracy than any other form of government. And more states, democratic or otherwise, increasingly see the value of a rules-based international order and the need to play a greater role in sustaining it. For this reason, we see increasing strategic cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region between the United States and its treaty allies, especially Japan and Australia, but also between these countries and emerging powers such as Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, and, of course, India. Indeed, the growing partnership between India and Japan is perhaps most encouraging.

India and the United States must play a leading role, both together and with other like-minded states, to strengthen a rules-based international order and a favorable balance of power in Asia. None of this means that India or the United States seeks to antagonize or exclude China. Both our countries want a constructive relationship with China, which is in our interest, and China’s too. The India-U.S. strategic partnership, in all its forms — diplomatic, economic, military — is critical to encouraging China to rise peacefully in the present order, rather than trying to unilaterally and coercively change the status quo. More provocative to China than any of this is the perception that India and the United States are weak and divided.

Whether it is steps our countries can take to enhance our influence, or to project our influence together, the meeting between Modi and Obama is an opportunity for true strategic dialogue — an open discussion of the big questions. What kind of world do we want to live in? What are our true priorities amid a large bilateral agenda? And, most importantly, why does this partnership still matter?

As always, there will be skeptics on both sides. There will be Americans who tell Obama that this strategic partnership is overhyped, that India will never get its act together, and that it cannot be trusted to cooperate with us in a meaningful way. There will be Indians who tell Modi that drawing closer to the United States is a liability, that the United States is in decline, and that it is increasingly unable and unwilling to exert resolute global leadership.

We need to refute these skeptics, because it would be disastrous for both countries if we fail to reach our full potential as strategic partners. For India, it would mean squandering perhaps the greatest external factor that can facilitate and accelerate its rise to power. And for the United States, it would mean missing an irreplaceable opportunity to shape the emergence of a global power that could lead the liberal international order together with us long into the 21st century.

Obama and Modi must know that our relationship will continue to face short-term frustrations, and setbacks, and disappointments. But ultimately, this strategic partnership is about India and the United States placing a long-term bet on one another — a bet that each of us should be confident can offer a big return.

Americans should have confidence in India. It will soon become the world’s most populous nation. It has a young, increasingly skilled workforce. It is one of the world’s largest economies. It is a nuclear power that possesses the world’s second-largest military, which is growing more capable and technologically sophisticated. And India is a democracy, which does not mean its economic and social challenges are less daunting, but that it is more flexible, more responsive, and better able to address those challenges than its undemocratic peers.

Indians should also have confidence in the United States. Our economy remains the most dynamic driver of global growth. Our society remains virtually limitless in its capacity for reinvention, innovation, and assimilating new talent. Our institutions of higher education remain the envy of the world. Our military remains the most capable, combat-proven on earth. And we now have vast new supplies of energy.

India and the United States should have confidence in one another, and in the promise of their strategic partnership, because of our common capacity for renewal, which derives from our shared democratic values. It is this shared virtue that enables us to ask ourselves hard questions and to change when change is needed. As long as our nations stay true to these values, there is no dispute we cannot resolve, and nothing we cannot accomplish together.

This essay was adapted from remarks delivered at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on Sept. 9.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine