Science and Sales: The Hard Sell, Crime and Punishment at an Opioid Startup – A review

by Sandy Singha Roy

With two TV serial programs focused on Purdue Pharma’s CEO, Dr. Richard Sackler and his predatory opioid empire built around the drug Oxycontin, now, having explored that company’s responsibility for addicting and killing the multitudes of Americans addicted to its flagship drug, we thought we had heard it all.

The Hard Sell Crime and punishment at an Opioid Startup, narrates a story that clearly proves that there is much more to the story of corporate America criminally ignoring all canons of ethics to make money from something as basic as human suffering.

The Hard Sell Crime and Punishment at an Opioid Startup

Publisher : Picador 2023

Language : English

Paperback : 235 pages

ISBN-10 : 0385544901

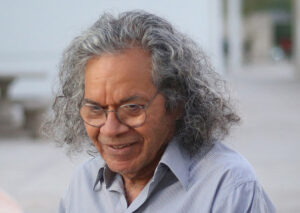

Author and journalist, Evan Hughes (Literary Brooklyn) does a revealing job of taking us into the world and investigation of pharmaceutical manufacturer Insys Therapeutics, the leadership of which was convicted in 2019 of federal racketeering and conspiracy charges. Headed by John Kapoor, the eccentric and brilliant founder of the Arizona company, complete with Einstein like uncontrollable wavy hair, the court found that he and others had bribed doctors to prescribe their fentanyl-based pain medication Subsys even when medically unnecessary.

The story starts when Kapoor, allegedly moved by his wife Edith’s early and painful death by breast cancer, endeavors to relieve the suffering of others similarly afflicted. Pain from Cancer he was known to say was like no other. As Subsys was developed for cancer patients, and provided near instant relief because of its revolutionary and patentable spray delivery system for Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid one hundred times more potent than morphine, the company initially seemed the result of a mainly altruistic effort to help people with chronic or end stage cancer deal with their acute pain. For such patients, issues like addiction and dependency were virtually irrelevant. Facing one’s last days in some kind of comfort and dignity was of paramount importance.

Chairman Kapoor hired, Micheael Babich, a young man without a medical or pharmaceutical background to run the company. He ultimately turned state’s witness against Kapoor. Babich recollects Kapoor’s interests quite differently. According to Hughes, “In Babich’s narrative, the clear business potential of the product figures more heavily than Editha Kapoor’s (John Kapoor’s wife) health history. Everything stemmed from Kapoor’s observation that the spray delivery was not only scientifically promising but remunerative… Kapoor observed that sublingual sprays could be priced much higher than pills…and couldn’t see why more weren’t’ being developed.”

Kapoor had already shown himself to be a sketchy mover and shaker before he started Insys around 2002. An earlier pharma company he ran, Lyphomed, was flagged by the US Food and Drug Administration in the 1980s. Other drug companies he controlled in the 1990s and early 2000s faced foreclosure, shareholder lawsuits and boardroom strife. Even so, he had by the time Insys was founded, become an extremely wealthy man, worth hundreds of millions of dollars. He could have have lived comfortably in retirement in his opulent mansion in an exclusive gated community in Phoenix Arizona, run a restaurant chain he was starting, and be intimately involved in the many charities to which he donated. While his wife’s death may have spurred him to start a drug company whose sole product was a painkiller, the only logical conclusion one can draw from his continued pushing of the drug against medical advice, and engaging in the criminal activities to enhance the bottom line is singular: greed.

Through a myriad of official documents, including court records, as well as interviews with more than 100 people, this well-researched book details the tactics Insys executives and employees used to burnish sales of a narcotic that should have been prescribed sparingly and carefully – that too to cancer patients for whom it was initially developed as a spray drug.

Insys took a page from Sackler’s playbook, holding speaker programs, in which they paid doctors speak in public at conferences about the benefits of their products, touting the practice as a learning initiative or continuing education for other physicians. Insys made no effort to hide that it was paying doctors to prescribe Subsys. Ineed, Kapoor created a document that calculated the return on investment of each speaker, records which even subordinates thought was a bad idea to keep. They were proved right when became critical to law enforcement demonstrating Kapoor’s complicity in the bribery scheme.

The billionaire founder of Insys Therapeutics Inc. John Kapoor, exits the federal court house after a bail hearing in Phoenix, Arizona , U.S., October 27, 2017. REUTERS/Conor Ralph – RC1FFA4BB100

Even more astonishing was a program called the Insys Reimbursement Center, in which Insys workers would call insurers on behalf of doctors’ offices to get them to authorize payment for Subsys, which was approved only for cancer patients. The center’s workers had access to patient records, and they read from scripts saying things like, “The physician is aware that the medication is intended for management of breakthrough pain in cancer patients, and the physician is treating the breakthrough pain.” Hughes notes that the person fielding the call was not a medical expert and in the hurricane of words, spouted by the caller, cancer wasn’t specifically mentioned, misleading the insurers. Also, by farming out pre-authorizations for insurance coverage to an Insys contractor, Hughes notes this to essentially be a kickback.

That Insys was able to openly break laws for so long is a searing impeachment of an interrelated regulatory, legal ecosystem ostensibly established to protect the public. A sales rep for Insys filed a whistleblower lawsuit against the company in September 2012, compiling documents, emails and even voice recordings to make his case, yet the government declined to intervene. “Although the Justice Department prefers not to discuss it openly, there is plenty of illegal conduct in health care that never gets prosecuted, owing to limited government ‘bandwidth’ and the daunting burden of proof,” Hughes writes. That same lawsuit was unsealed in March 2013, but Wall Street paid no attention: Insys went public in May of that year and became the best-performing IPO of 2013.

While detailing the morally repugnant conversations that took place among low-level sales reps, marketing executives and other figures who devised schemes to push Subsys, he is less scrupulous and meticulous about ascribing blame to those in the financial markets who were complicit in boosting Insys as a public company such as the underwriters who took this obviously shifty company public, and the analysts that blindly pumped it as a ‘buy’ stock. He mentions scant little about the blue-chip board of directors, and fails to explain why, when presented with an overdue internal investigation of Insys practices did the board and chief executive ignore recommendations to terminate bad actors.

The entire opioid business seems to have been awash in these underhanded tactics; as Hughes notes, “Nothing that Insys did was truly new.” Indeed, what’s most surprising and powerful about The Hard Sell is not one company’s criminality — the public has grown used to corporations behaving badly — as much as how these practices were institutionalised across the drug industry and the financial markets, which until the indictments were rolled out, continued to tout Insys as a strong buy stock, rallying the stock price even after a dip that followed the announcement of the initial investigation.

Ultimately, Hughes does an admirable job of illuminating the inner workings of Big Pharma’s malicious practices. However, by the end, it’s unclear how much damage Subsys did in the context of the broader opioid epidemic. There are tales of people overdosing and becoming addicted, of lives and families shattered, included in the story but one is left with an incomplete conclusion on whether Subsys was a key element of the root cause of the opioid crisis or merely a contributing factor.

While stating that Fentanyl, itself, has been a “prolific killer”, being implicated in approximately two-thirds of all opioid overdose deaths in 2018, Hughes admits that the vast majority such cases are the result of consumption of illicitly manufactured Fentanyl and not those drugs made by pharmaceutical companies and prescribed by physicians. He notes that, unlike natural opioid derivatives, which come from the poppy flower, Fentanyl can be made in a clandestine lab. “It is easily trafficked, often from China or Mexico; its potency means a small package can deliver a large payload.” Considering these facts, notwithstanding Insys’ wrongdoing, one can hardly claim that its primary product, Subsys was responsible for rampant opioid deaths and ruined lives from addiction that the United States faced in the late 2010s.

What’s interesting is that authorities went hard against Insys, a company run by a brown-skinned immigrant but none of the well-connected white-skinned Sacklers of Purdue pharma got any jail time. Indeed, the executives who were criminally charged were permitted to plead to misdemeanors, keeping them out of prison. While Kapoor and his cohorts rot in prison, today, the Sacklers are reportedly still worth hundreds of millions. And, it is clear that Purdue Pharma was the major cause of the opioid crisis. The story, in the end, appears to be one of law enforcement going after low-hanging fruit, and gaining convictions to tell a story that they ‘got the bad guys’ while the multitudes of opioid addicts remain dead or are still dying. These is a narrative that Hughes avoids for reasons only known to him, and remains the book’s only small but real flaw.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine