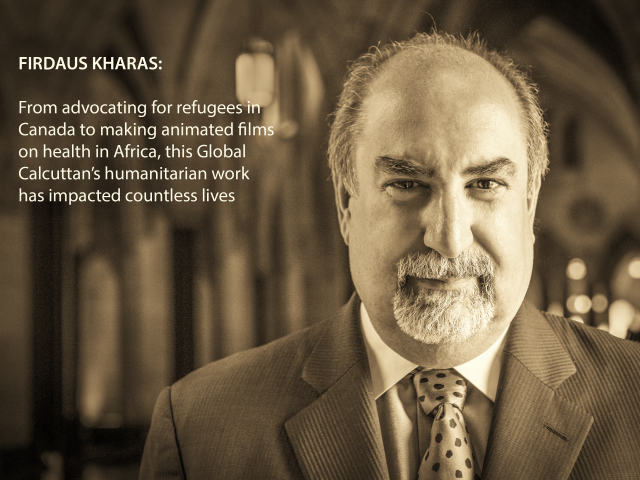

Quest to Spread Dignity, Born in Calcutta

‘In 1965 at age nine I saw my first refugee when I went to the train station with my mother to meet those coming in from the India-Pakistan war (zones). They had nothing; we gave them shampoo, and even this little thing helped restore some of their dignity. Our role was to do what we could. That’s never gone away.’ – Firdaus Kharas

Firdaus Kharas: Such a Long Journey

By Mike Levin

Sick adults can’t contribute to economies; chronically ill children drain a family’s resources; and women and children afraid of rape and domestic violence can be cowed from participating fully in their cultures. This is simple logic, and for reasons that Firdaus Kharas can’t always understand, much of the world has yet to apply that logic.

Kharas, however, has always used his confusion as a tool, one that drives him to make his own changes, especially aimed at children who are always the first victims.

He stays clear of the financial accounting that seems to constrict so many of today’s development organizations, preferring instead to frame the problems of poverty, disease and tribalism as human-rights issues. He feels that without the belief that every human has a right to individual dignity, nothing will ever change.

Kharas has given up secure jobs and spoken truth to power in a quest to help create this dignity, and when he has run into personal and geopolitical roadblocks, he tries things that no one else is doing, like creating humourous animated videos to help combat HIV/AIDS or domestic and sexual violence.

He is a strange mixture or altruism, privilege and ego, filtered through a personality that refuses to be aggressive. This stew has been percolating for a very long time. Before most of us knew what was beyond our front gate, Mr. Kharas was learning lessons from his mother that would eventually make him believe he could change the world.

“I have always believed that our shared commonalities as human beings affirm that we will not tolerate mistreatment or injustice: if we can save a child’s life, we should; if we have an ability to lift a person out of the crushing burden of scarcity, that it is our duty; and if we have the talent to affect change for the better, then we must use it,” he says.

Firdaus Kharas is the second son of an engineer father and a mother who trained as a lawyer. Both are Parsi, although his mother grew up in England before marrying his father and moving to Calcutta.

His father was the director of a British firm that imported machine tools. This gave the family a comfortable, upper-middle-class life on Lord Sinha Road that included a large household staff and a comfortable niche in a 1960s city that was “either First World or Third World and nothing in between,” according to Kharas.

His mother didn’t write the bar exam in her new home and chose instead volunteer work with the Women’s Voluntary Service, soon becoming the Secretary-General for all of India. She often took along her youngest child during her daily duties.

One of those episodes happened in the 1963 when mother and son went to help at a charity house in the city’s Kalighat neighbourhood. There Anjezë Bojaxhiu was caring for any destitute person too weak to survive on the street.

Mother Theresa’s Home For The Dying didn’t scare the young Kharas. He watched people die in the dormitory beds and still returned several times to help with the chores.

But it did provoke the question of why a tiny Albanian nun (“a foreigner in a sari”) would care for Calcutta’s dispossessed. “There was a real dichotomy between this world and the one I lived in, and the only way I could understand it was in terms of there existing a duty to help.

“In 1965 at age nine I saw my first refugee when I went to the train station with my mother to meet those coming in from the India-Pakistan war (zones). They had nothing; we gave them shampoo, and even this little thing helped restore some of their dignity. Our role was to do what we could. That’s never gone away,” he remembers.

In his regular life Mr. Kharas attended La Martiniere Calcutta, often wading through the city’s monsoon-flooded streets hoping that his feet wouldn’t find a manhole that was uncovered. But in 1968 his father’s work took the family to Bombay.

The obvious academic choice for Firdaus and his brother Cyrus was the storied, The Cathedral & John Connon School.

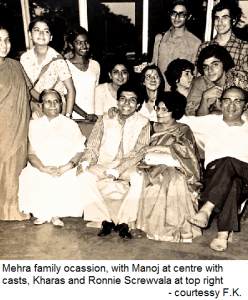

Firdaus excelled academically, being named House Captain, a Prefect, the leader of the school’s debating club and earning the top mark in English literature for the entire country in his final year. His only disappointments were barely passing grades in Hindi and Gujarati. But it was friendship with classmate Manoj Mehra (currently working for Time/Warner in New York) that created a major building block for his future.

The pair created their high’s school’s Junior Rotary Club (called the Interact Club) and every weekend they travelled to Bombay’s poor neighbourhoods to teach English, sometimes in a building, sometimes outside on the street. They also taught elderly disabled residents at Cheshire Home during the holidays. Yet by the end of high school they decided to leave India. “We didn’t see much of a future here to reach our potential,” says Kharas, who won a Rotary scholarship to do an additional year of high school in the United States.

The pair created their high’s school’s Junior Rotary Club (called the Interact Club) and every weekend they travelled to Bombay’s poor neighbourhoods to teach English, sometimes in a building, sometimes outside on the street. They also taught elderly disabled residents at Cheshire Home during the holidays. Yet by the end of high school they decided to leave India. “We didn’t see much of a future here to reach our potential,” says Kharas, who won a Rotary scholarship to do an additional year of high school in the United States.

Another schoolmate saw exactly what was happening. “…what struck me about Firdaus from those very early days was his ability to be level headed about everything,” Ronnie Scewvala, founder of UTV, told me via email. “Few are clear on career choices at that (young) stage but I remember that when Firdaus went overseas for his higher education he was the only one from a very large group of savvy youngsters who was clear on what he wanted to do and why.”

Kharas landed in Pennsylvania and discovered that American schooling was “ludicrously easy.” It gave him to time to experiment with a first girlfriend (an exchange student from Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe) and drama (he wrote plays and tried acting).

From Commodore Perry High School he moved 10 kilometres west to Greenville and Thiel College. His entire trunk-load of social attitudes went with him. He wrote many more plays, performed in theatre and won a national debating title. He finished a four-year undergraduate degree in three years with high honours, driven by an academic program in political science and a personal passion for human rights.

And while such stints can be comfortable for India’s post-liberalization elite, Kharas had to struggle to make ends meet. India’s foreign-exchange rules made it difficult to receive U.S. dollars. In his freshman year he traded food and board for work on a farm miles from the college, often walking between the two. One winter the staff at Thiel was so concerned about his inability to buy warm clothes that they organized a clothing drive for him.

While participating in a Middle East negotiation simulation in Ottawa, Canada, in 1977 he had a chance meeting with John Sigler, then the director of Carleton University’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs.

It lasted only a few minutes; Sigler offered Kharas a scholarship to attend the university.

Carleton’s buildings are joined by underground tunnels because Ottawa’s winters can be horrifically cold. Kharas says he spent his first winter in the tunnels and buildings, only once setting foot outside to walk on the city’s Rideau Canal, the world’s longest skating rink. The ice was fascinating, until he put a foot through it.

University life delivered a second shock when his 1980 Master’s thesis – a draft convention to ban a state’s use of torture – was poorly received by academic adjudicators. Even at one of Canada’s top university departments of international affairs, few could make the connection between conflict and human security that would take over as a dominant worldwide theme in the 21st Century. Kharas was ahead of his time, and suffered for it.

In his thesis, Kharas stated that outlawing torture must “present a self-interest argument. The answer is that torture produces, at best, short-term and limited advantages for its practitioners, while engendering greater disadvantages for the legitimacy, integrity and credibility of the system which advocates, permits or tolerates its use. The long-term implications to the preservation of the social order and political system which permits its use are far more detrimental than the limited tactical benefits perceived to derive these from.”

Despite being unquestionably accepted today, the theory was considered too dramatic, too brash. There was the insinuation that he didn’t have the experience to judge such pithy human affairs. Left unsaid was that speaking truth to power was not the role of an immigrant student who had only been in Canada for two years.

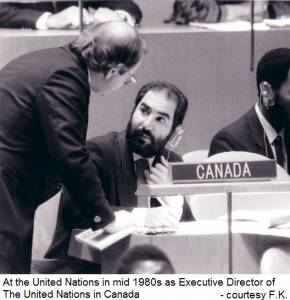

After graduation he started a company called Global Outlook that produced books on risk assessment in some developing countries and then took up a five-year position as Executive Director of the United Nations Association in Canada.

He then spent “a fascinating year” as Policy Advisor (Immigration and Refugee Affairs) to Canada’s Immigration Minister, helping make decisions on individuals seeking the minister’s intervention. In 1989 he was offered a contract as Assistant Deputy Chairman at Canada’s migration and Refugee Board. Here he was re-acquainted with the plight of refugees – tens of thousands of them whose cases were bogged down in the government’s system.

His job was to help clear up this backlog, which he did, but not before rubbing some people the wrong way.

Canada’s guilt about an inequitable world was at its peak, and the instructions from above were to allow virtually all claimants to stay. Kharas saw problems with this, and he voiced them.

Canada’s guilt about an inequitable world was at its peak, and the instructions from above were to allow virtually all claimants to stay. Kharas saw problems with this, and he voiced them.

“The system started dealing with immigrants as country groups rather than individuals. This meant they allowed in the persecutors and as well the persecuted. I railed against that,” he recalls, adding that he never was comfortable as a bureaucrat because of the rigidity it produces in implementing change.

“I was told not to re-apply for another term or even to seek another government job. I couldn’t deal with this style so I knew I had to do things my own way.”

Easier said than done, because Kharas now had a wife, a son Nicholas and a daughter Kaitlin. He also had a personality that didn’t fit easily into the increasingly deferential world of the private sector. He is polite and thoughtful but also driven by a need to control his environment. He has trouble accepting advice but can easily collaborate if the situation calls for it.

Finding a new path was not going to be easy.

For most Baby Boomers living in North America, mass media, and especially television, offered a world of potential. It could reach everyone, assuming one could find a way through the electronic noise. He understood he couldn’t do it alone so in early 1995 he looked up Screwvala, who five years earlier had started a media-software company called UTV out of his own home.

Within two decades it would become a worldwide communications conglomerate, eventually selling control to the Disney Corporation in 2012. But in 1995 it

was just starting to stretch TV production outside India.

Kharas was asked to oversee this international expansion. He created UTV Canada for his own, often non-profit, work and then went travelling to see where Screwvala’s productions could land outside India. He tried South Africa first but deemed it too volatile. Then came Malaysia and Southeast Asia, a fertile media environment.

Kharas formed a partnership with the Malaysian Royal Family’s Antah Group and added another withRupert Murdoch in Singapore. One of the first results was a ground-breaking soap opera called City of the Rich, a daily hour of hopes and sighs, although no sex.

“I’ve always said it was a terrible drama but also the most innovative media at the time. It was the first-ever Asian drama series entirely in English, and we built two studios in Kuala Lumpur and two in Singapore (to deal with the demand for new episodes). We were also the first to train local cameramen, to move camera shots like Western productions. I remember I had to tell the cameramen to look through the camera rather than at the ceiling when shooting,” Kharas says.

City of the Rich was a huge success and can still be found in reruns today. But the strain of being away from his Ottawa family for months at a time was

taking its toll.

Within a year he moved out of the UTV brand, renaming UTV Canada as Chocolate Moose Media (CMM), and returned to Canada full time.

“Ronnie had a long-term view that would take the company public, so his emphasis was on the commercial. I wanted to mix my work with for-profit and

non-profit productions,” Kharas recalls.

He knew he had to stay with TV and video, media that could draw all the threads of his life together.

He visualized a hybrid entity that could support its own social benefits. Again he was ahead of a curve that hadn’t yet named the concept. Today it is

called a B Corporation in the United States and a Social Enterprise in the rest of the world.

Screwvala saw it coming. “Firdaus had by then devoted many years to pubic service by serving in the Canadian government and so was always clear of what

impact he wanted to make on the global stage. Now to do this by balancing the commerce of it with the impact is always difficult, and where most (people)

struggle and cannot do this for the long term and in a sustained manner at scale, but Firdaus has been able to marry this very well as is evident from his now body of work,” he says.

The early years of CMM focussed on creating revenue with animated series for children and with the occasional film. Kharas brought to life Canada’s beloved For Better Or Worse comic strip and a dozen other series. He was also involved in film,including a supervising producer credit on Such A Long Journey. It provided a steady income stream.

Alongside this came a series of activist projects. The first was in 1996: Cartoons For Children’s Rights,

commissioned by the United Nations. It brought together 70 studios in 32 countries; Kharas oversaw distribution and produced several of the videos. The 66 spots have been broadcast by 2,000 TV stations in 132 countries. With this work came a deeper understanding of how children are much more open to behaviour change through media, and how animation has a much better chance of being accepted by multiple cultures because of its non-threatening nature.

In 1999 he created a short, non-animated TV documentary about the AIDS pandemic in South Africa then the next year produced Animated Jam for UNICEF,shorts from 14 animators that dealt with health, education and equitability from a child’s point of view.

When he met South African producer Brent Quinn in 2002, Kharas’ path steadied, and strengthened. The duo collaborated on an idea of “behaviour-change communications” that would use public service announcements (PSA) to get vital messages across. They would be animated, short, funny and completely different from other media that dealt with subjects like AIDS, disease and violence.

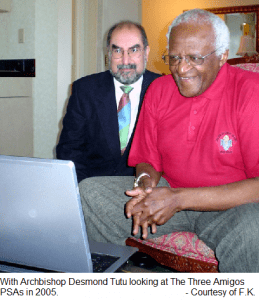

One of their first creations was a series called The Three Amigos, PSAs that used three cartoon condoms – Shaft, Stretch and Dick – to spread knowledge about safe sex. If you can make people laugh by comparing sex without a condom to betting everything you own on one roll of a roulette wheel, the message will stay in their minds. If you can do this 20 times in 75 languages reaching billions of people in their own languages, you can change public attitudes.

The World Health Organization and United Nations used the animated shorts in their worldwide campaigns against the spread of HIV/AIDS, as have dozens of

other organizations. The Three Amigos was previewed at a 2004 conference in Bangkok, and Mechai Viravaidya – Thailand’s Mr. Condom – immediately asked for copies to use at his foundation. New cases of the disease in Thailand dropped from 68,000 to 9,700 between 2005 and 2011. Figures are even more astounding in South Africa where until 2005, AIDS was a national emergency. Since then, new infections have dropped almost 30 percent.

The Three Amigos received support from individuals like Nobel Prize laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu. It also won a prestigious 2006 George Foster Peabody

Award, among dozens of other awards.

This was followed by Buzz and Bite (2008), a series that aimed to help prevent the

This was followed by Buzz and Bite (2008), a series that aimed to help prevent the

spread of malaria, and No Excuses (2011), a controversial series that condemned cultural validation of domestic and sexual violence. The formula has always been the same: animation, humour and multiple languages.

We consider Firdaus Kharas to be the modern equivalent of Dr. Seuss,” says Vanessa Breen, director of Dublin’s Malaria Museum.

During this, Kharas kept his for-profit work active, although he has always inserted a human-rights theme into the mix, however discretely. Two series for

Al Jazeera Children’s Channel in Arabic – Nan and Lili;

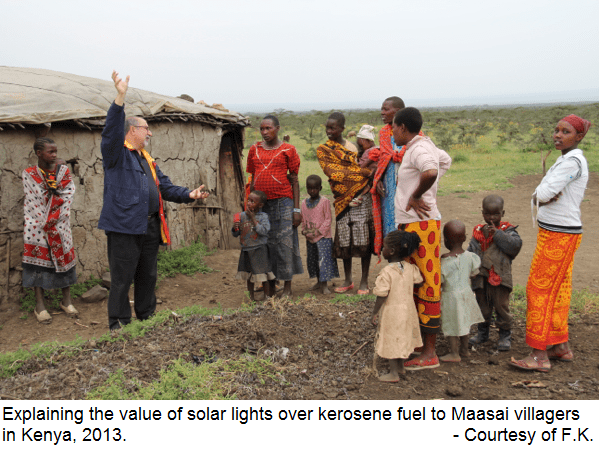

Other activist productions included Child Without A Country: Pedro – a documentary about a refugee caught in Canada’s immigration system; No Thanks We’re Fine– a documentary about the trials of caregivers for people living with dementia; and The Solar Campaign – an animated series that educates those in places with no access to electricity about the value of solar energy rather than toxic traditional fuels like kerosene. In 2013 Chispa Productions released a documentary about Kharas’ path called The Animated Activist.

Kharas is also a noted speaker, author and media jurist. His list of awards is far-too long to list here. He has received an honorary doctorate degree from Thiel College, was short listed for The Guardian’s 2013 humanitarian International Achievement Award and was named one of the world’s 50 Most Talented Social innovators by Mumbai’s World Corporate Social Responsibility Congress.

In 2014 came Ebola: A Poem For The Living, an emotionally compelling video with one goal: to help prevent the further spread of Ebola during the West African epidemic. Co-written with Quinn and backed by Andrew Huggett’s powerful musical score, the four-minute animated video tells the story of a young boy’s death from the disease. During the final hours of his life, he pleads with his family in a fevered dream to see past the myths and misinformation that had sprung up around the disease.

By March 2015 it had been viewed more than one million times online and had been embedded in 500,000 Web pages. This was primarily because the video had been dubbed into 17 languages and could be understood by 80 percent of the people in towns and villages in the afflicted areas.

“(Kharas) really understood that to have an effect, any Ebola information would have to be available in languages that people (caught in the epidemic)

could understand. I don’t remember anyone else who saw that,” says Grace Tang, Nairobi-based global co-ordinator for

The video’s production was a gem of international co-operation. A feature on its making is available on Chocolate Moose Media’s Website.

This was mass communications at its most effective, especially considering that the world’s largest humanitarian organizations had been slow to respond and made virtually no effort to tell West Africans how to protect themselves in languages they could understand.

Reports about the video from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea and the Ivory Coast were so positive that it prompted UNICEF and United Methodist Communications (which funded Ebola: A Poem For The Living) to request a second version for use in other West African areas that could be the disease’s next epicentres.

Kharas is also currently at work on a new series about the stigma of childhood diabetes, funded by the Qatar Diabetes Association.

Yet his position today is just as precarious as it was wading through chest-high water of a Calcutta monsoon. His name is immediately recognized in countries where his work has filtered into the humanitarian firmament. But he is virtually unknown in the Western world, especially in his home country of

Canada where we are so safe and secure that giving $100 to the Red Cross absolves us from paying any further attention to the plights of others around the world.

Kharas’ quest to spread human dignity is an uphill trek, complicated by geopolitical issues far beyond the scope of individuals. But his ideas do have a theme that is universal within almost every one of those individuals.

Human rights are only possible when there is mutual respect, and respect is only possible when there is optimism and hope. Kharas is certainly not the only one trying to make the world a more hopeful place. Yet his path from Calcutta to a world stage would have been impossible without a life-long, and unshakeable, belief that every human has the same rights.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine