Atwood’s The Testaments: A Thriller That Lays Society Bare

<SB VEDA>

“History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.”

In 1985, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale introduced readers to a repressive fundamentalist Christian regime called Gilead in which women are used as commodities to, firstly, reproduce – and then to serve its leadership in various ways from menial tasks to enforcement of discipline. Narrated from the point of view of one of the human gestation vessels or Handmaids, the dystopian novel takes the reader into reader to a chilling and oppressive world. Represented as it is through the narrow lens of one of the constrained, the reader experiences the claustrophobic experience of the Handmaid. The novel deals with the feelings, Offred, (literally of a male named Fred, the Handmaid’s first owner) her interactions and attractions, and at the end, the uncertain fate she faces as she tries to take matters into her own hands.

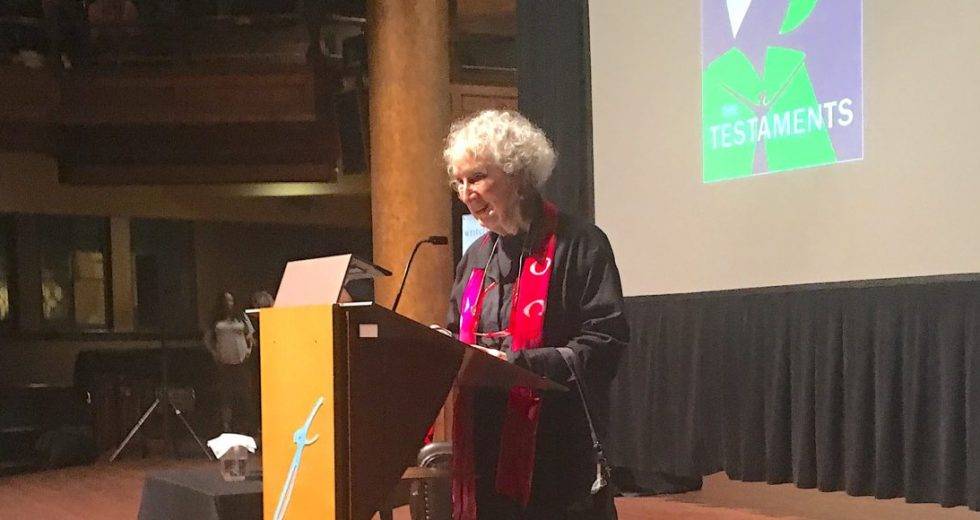

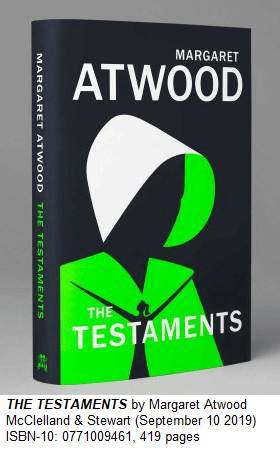

The story became a cult classic – a phenomenon that was adapted time and again. The relevance of the novel to the America of Donald Trump, spawned a TV series, recently concluding its 3rd season, and the Handmaids’ red uniform and white wings became a symbol of resistance for women against the open misogyny of Trumpian mores. When the novel, The Testaments, which continues the Gileadean story, was published, last month, it was the literary event of the year: the book debuted as a shortlisted title for the Man Booker Prize. (Since publication of this article, Atwood went on to win the Booker prize along with Bernadine Evaristo for another feminine themed book, Girl, Woman, Other.)

Rather than leverage the momentum of handmaid memes and the like, Atwood chose to leave that thread behind in The Testaments. True to Gileadean form where women are mere witnesses, Atwood sheds new light on this society and ours in the form of testimonies from three different perspectives. In doing so, she narrates how Gilead came to be, what role the female enforcers (or Aunts as they are known in the story) played in its founding, and how children born into it have fared. She also explores the outside world as a reaction to Gilead, notably, a resistance (Mayday to whom Offred had appealed to get her out of Gilead in the original book) that operates out of Canada where one of the narrators, Daisy, has lived most of her life.

The Handmaid’s Tale ends with a symposium (the 12th Symposium on Gileadean Studies) that reflects upon Offred’s narrative contained in tapes she left, which comprise the story, concentrating on issues such as authenticity. At the end, the chair asks, “Are there any questions?” Atwood has admitted that, after publication of the book, questions were in infinite supply; The Testaments, is her best attempt to respond – a response that is filled with revelation, intrigue and increasing tension. Indeed, the novel reads like a highbrow thriller with implications on how we’ve ended up with Donald Trumps, Boris Johnsons, and Jair Bolsanaros.

The most interesting of the three narrators is Aunt Lydia, one of the founding Aunts of the regime who, in flashbacks, recalls her former life before the regime and how she was captured by it and then co-opted to serve it. Her recollections are informative, depicting an insiders view of Gilead, much of which is shrouded in mystery in the first book. In doing so, Atwood, portrays Aunt Lydia in a not unsympathetic light. She recalls her climb from trailer-park trash to being appointed a judge, all the while trying to do what was right, better the world that made her. Instead of gaining some reward, she is arrested when the Gileadean coup takes place and tortured:

“I was a family court judge, a position I’d gained through decades of hardscrabble work and arduous professional climbing,” Aunt Lydia attests. “And I had been performing that function as equitably as I could. I’d acted for the betterment of the world as I saw betterment, within the practical limits of my profession. I’d contributed in charities, I’d voted in elections…held worthy opinions. I’d assumed I was living virtuously; I’d assumed my virtue would be moderately applauded. Though I realized how very wrong I had been about this and about many other things on the day I was arrested.”

How does a regime such as Gilead come to be? This much was signaled by Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale: “In a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it….We lived, as usual, by ignoring. Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it.” And, as American society simmers slowly to a boil, Atwood continues her prophetic story by providing the details of Aunt Lydia’s conversion from prisoner to warden.

Lydia constructs her testimony on pages that are appropriately stuffed into an old copy of Cardinal Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua; A defence of One’s Own Life. Hers is a defence of sorts, looking forward to how she might be viewed after the regime falls as one of its icons. This puts her in some peril but she reasons that with Catholicism having been deemed heretic in Gilead, that the pages were safely hidden within that forbidden book. It is telling that even someone in a position of influence like Aunt Lydia should need to hide her personal diary, for there is no privacy for women in this republic. Even the most powerful must remain ever vigilant, guarding the personal from eyes unseen.

While we understand that the totalitarian Gilead has pushed out or exterminated religious minorities, we assume this also to mean racial minorities, though the TV series based on The Handmaid’s Tale has not excluded them (perhaps Hollywood’s attempt to grapple with lack of diversity). Atwood, therefore, unapologetically does not deal with racial discrimination in Gilead. It simply isn’t a factor in the story, and many find this to be a drawback. The question is, would the dialectic of white vs. black/brown have brought about a new dimension to the story or overcomplicated where such an element was not needed? One might liken Gilead to North Korea – race isn’t a factor because of the relative homogeneity achieved In the story. Of course, this runs counter to concepts of pre-Gileadan USA as a multicultural society. Just how the society became so homogeneous is a gap that could have been filled. This seems like something of a missed opportunity as it would surely have made the plot even more relevant in the wake of Trumpian racism, and maybe foreshadowed what is to come should the USA continue in its present trajectory.

In the fifteen years since the original story, Gilead is no longer so formidable. The power structures firmly in place in the original (with only hints of stress in The Handmaid’s Tale) are cracking from within. Fear and mistrust abound, and this breeds various kinds of plots, surreptitious plans and actions lead to various kinds of rebellion, both small and significant. Indeed, Aunt Lydia uncovers and responds to a plot to get rid of her.

As Atwood explores the roles of women in different social classes – the brown Aunts and their Supplicants, blue Wives, green Marthas, and red Handmaids as well as men at the top like Commander Judd, uncertainty binds each narrative thread. Each testimony account reveals an existence under duress, and the tension only mounts as the story progresses. Even the formidable Commander Judd’s position is subject to the auspices a higher council who may purge him at any time.

Aunt Lydia also recognizes the uncertainty, noting: ““The Wheel of Fortune rotates, fickle as the moon…Soon those who were down will move upwards. And vice versa, of course.”

That said, Aunt Lydia’s testimony informs us that to a significant degree, the Aunts are queens of their domain, protected where they reside at Ardua Hall – a place where men may not enter without permission. But if one expects sisterhood to have bound the aunts together, think again. The story takes on the elements of a spy novel with various intrigues cropping up between the Aunts, among wives, and at the level of the commander. Even the gossiping Marthas have a role in disseminating information in a regime, which severely limits the expression of women.

We come to understand the power of the word, for in Gilead, reading for women is banned. Only the Aunts have access to books – and the most ‘dangerous’ books, those containing words, thoughts, phrases exposing bitter truths – carry extremely limited access. Exposure to truths is what finally influences the actors in Lydia’s plan to bring down Gilead, to spring into action.

It is through reading these forbidden words that the character of Agnes (one of the two teenagers whose testimonies bookend Aunt Lydia’s) finds out her destiny. By this time, we’ve figured out that she must be Offred’s daughter, the one who was taken from her when the Gileadean coup took place. When we come to know that Agnes’ Canadian counterpart, Daisy was also brought up by parents who were not of her blood, it isn’t long before we hope that she, too, is Offred’s – the child she is carrying at the end of the The Handmaid’s Tale.

Agnes and Daisy’s stories are engaging being parallel lives in vastly different circumstances, linked by the common thread of lack of history. Uncertainty of parenthood juxtaposed with with loss of parental figures further fuse their separate existences. The two must learn to fend for themselves. Daisy literally gets lessons on self-defence while Agnes learns tactics similar to those employed by Lydia, which are more suitable in a tightly controlled world.

Their stories, however, are the weaker aspects of the novel. Atwood is more adept at portraying Lydia with her aged survivors’ wisdom and sardonic voice. The teenagers are not so successfully rendered. Indeed, Daisy’s physical training and exercising are almost unintentionally comical.

Still Atwood’s words are crisp and artful with phrases elegantly turned. In a year during which fellow Booker Prize nominee, Salman Rushdie made an obsession of literary allusion in his novel, Quichotte, Atwood’s references are more subtle – and thereby more powerful. Mephistopheles is invoked as Lydia describes her Faustian bargain with Commander Judd, and in it, her end is foreshadowed. True to character, she does not become a victim of circumstance, and remains the driver right through to fitting conclusion.

Still a judge at heart, Lydia must act as instrument of justice if not retribution, for without it, her evolution from adjudicator of a district court in the United States of America into Aunt of Gilead becomes meaningless. She exposes a pedophile, saves Agnes from certain doom in marriage, and puts into motion a plan to bring down the regime, itself, bringing ruin upon her original captor and later collaborator, Commander Judd, in the process.

Biblical allusions are appropriately made, throughout. In a reference to the Trumpian post-truth era, Atwood explores how the words in the Bible are twisted to serve the ends of the regime and keep its pawns in their places. Here, the role of the education system in molding thought is cogently depicted. One can extrapolate this to mean the media (which while non-existent in Gilead) is meant to inform and educate just as schooling does. Gilead exemplifies and end to which Trump’s delegitimizing of the media with the label “fake news” and general denigration of journalism can well lead.

As in The Handmaid’s Tale, flowers as symbol of fertility and cycle of life, figure prominently in the prose. This time we read of flowers drying up, signaling an inevitable end. Lydia observes: “the daffodils have shriveled to paper and the tulips have performed their enticing dance, flipping their petal skirts inside out before dropping them, completely.”

Use of the moon is also symbolic: just as its waxing and waning indicates that nothing is certain, the cyclical nature of the phases of the moon hint at the circular nature of history. Indeed, Atwood paraphrases Twain in this, “History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.” A full moon near the beginning of the novel reminds Lydia of Easter and pagan fertility goddesses. A crescent moon near the end acts as a guiding light for Agnes and Daisy as they make their way to freedom, hinting that the moon as history may offer a guiding light for liberation from oppressive cycles. A full moon pits the pair against a tide at the end. Putting a cherry on top, the chair of the Thirteenth Symposium on Gileadan Studies (just as the Handmaid’s Tale had ended in the Twelfth Symposium) reflecting on the historical evidence of the testimonies, is named Crescent Moon.

Atwood maintains a Shakespearean tone throughout. The testimonies act as soliloquies, there is deliberate coincidence, and the re-uniting of siblings is a signature Shakespearian theme. Like Shakespearean works, The Testaments is perhaps more focused on entertaining than informing. In that way, the book is hard to put down.

While The Handmaid’s Tale had foreshadowed the demise of Western Liberalism, The Testaments is a critique of neo-totalitarianism/ neo-fascism. It explains how people like Trump get elected and stay in power. Aunt Lydia put it best, “Better to hurl rocks than to have them hurled at you,” she muses. “Or better for your chances of staying alive.”

What The Testaments doesn’t do is offer a realistic way out. Aunt Lydia’s solution, which is Atwood’s plot solution is simplistic and unlikely. It offers scant insight on how Americans can navigate themselves out of the morass of their own Gilead. Perhaps Atwood is pinning our hopes to the ability of the teenagers of today, to fix things – that is, after they’ve had their avocado toast.

One hopes that as impeachment proceedings move forward against Donald Trump, that a Lydia deep inside his administration might well be sitting down with this book and letting Atwood’s words make their impression. Otherwise, our only hope is to escape like Daisy and Agnes in a world in which safe harbours are becoming increasingly rare.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine