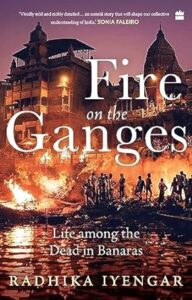

Learning from the Burning Ghats: Fire on the Ganges – a Review

Fire on the Ganges: Life Among the Dead in Banaras

by SB Veda

She is not merely a body of water; she is a Goddess, Ganga. The devout Hindu worships her. Politicians invoke her with unashamed bluster. The 560 million men and women who live along her banks pledge their livelihood to her. She is ‘ holy’and ‘pure’, the stream that is Indian history. In fact, most Hindu households use a bit of her in their daily puja rituals, so she is part and parcel of Indian life.

It is no wonder that Hindus scatter the ashes of their dead in the holy river. But what of those who cremate the dead? Until recently, when Radkhika Iyengar, painstakingly took the testimonies of the Doms, a dalit outcaste community who by virtue of ritual are bound to engage in cremation of the dead; living by ghats of Varanasi where many of the dead are burned and then dispersed into the Ganges, their stories were largely unknown.

Publisher : Fourth Estate India (29 September 2023)

Language : English

Hardcover : 352 pages

ISBN-10 : 9356994676

In her remarkably candid account of the lives of this community called Fire on the Ganges: Life among the Dead in Banaras, Iyengar illuminates the subject to a level never before exposed to the general public.

The book begins with an account of the life of a thirty-five-year-old widow named Dolly, and could be set really anywhere in India. She is thin with poor posture, owing to years of child-bearing, and tends to a shop run out of her tiny home. However, being a Dom, her mud-brick home is hidden from the main arteries of the city, and embedded in a winding “labyrinth of narrow alleys, hemmed in by walls plastered with drying dung cakes or exhibiting hand-drawn art,” according to Iyengar. What is particular about this area is that each house is nameless and bears no address.

“Most families in the neighbourhood live in cramped one-bedroom accommodations. At night,” writes Iyengar. “At night, temporary partitions re put up with bedsheets draped on ropes to make smaller rooms within.”

Iyengar describes a community in which caste divisions are entrenched so much so that, “an invisible boundary ezitst between the Chaudhary and the adjoining Yadav colonies. Both communities, however know where that boundary begins,” she writes. Iyengar continues: “If a married Dom woman wants to walk beyond this lin, she must pull her veil down to her chin and wait for her husband or another male famiy member to accompany her.” Young and unmarried women cannot walk off alone on a whim either. “It’s simply not allowed,” Iyengar quotes an elderly lady from the Dom community.

We find out that women in the Dom community are constantly under surveillance. Similar to other places in India where a wife takes her husband’s name, Dom women assume their whole identity. Without her husband, a woman is perceived to have no real essence at all. Dolly is quoted tragically as saying, “Tell me who am I without my husband?”

She alludes to his death, falling off of a bridge but with no broken bones or abrasions on the body, Dolly hints that her husband’s death could not have been an accident. But in in her insular community, making a police complaint and trying to find justice for her husband are luxuries she cannot afford.

Dolly’s story is just one example of the reportage of Iyengar: in crisp and vivid prose, she elucidates the daily grind of these unfortunate people. Some have feet that look like charcoal, others ash permanently in their saliva, still others suffer heat boils. She describes their daily toil, often having to manipulate the dead bodies whose bones stick out inconveniently; they have to be mashed into a similar consistency as the ash, else the customer will not be satisfied.

While Banaras is considered to be a holy city where many religious rites are performed at the ghats of the Ganges, for the past three thousand years, it has also been associated with death. Those who handle and cremate the dead are treated something less than human. The city, itself, though its literati claim is becoming more open is one of the most societally stratified areas of the world. Indeed, contrary to that set down in law, which prevents discrimination based on caste, Iyengar writes of Dolly’s account describing a state of being in which she cannot even share the same walking lane as an upper caste Hindu, lest she suffer verbal abuse. Should she touch the person by accident, she could be threatened with physical violence.

It is fitting then that death and division form central themes in the book, and are explored in detail.

The book’s title alludes to the open-air burning of the dead next to the river, which form the last rites in Hinduism. Through vivid descriptions of these ultimate realities of life as well as the ailments that afflict those responsible for arguably one of the most important aspects of the cycle of life such as alcoholism, drug abuse, addiction to Gudka, etc. and by describing the hierarchies that of Doms, particularly the women, Iyengar has managed an extraordinary narrative feat.

Writing elegantly and with an abundance of simile and metaphor, Iyengar evokes a lyrical vision of this damnable place. The narrative is rife with phrases such as, “Wild stories had begun to take root. Stories, which in Komal’s father’s mind were obstinate weeds that had to be pulled out.”

Iyengar brings to light the jarring realities of an extraordinarily oppressed class of people. Yet hanging on the end of the shock and horror is a strand of hope that attaches to the lives of people like Dolly, who becomes the community’s first female entrepreneur. Iyengar also describes a school, which welcomes all castes from which a boy named Bhola graduates, goes to college in Punjab, and gets a job in the city, escaping the entrenched existence he would face burning bodies in the ghats of Banaras.

Moreover, deep inside the maze of lanes and the squalor of daily existence, even exists romance in which as Iyengar describes a giggling girl entranced by the object of her admiration is just a giggling girl – something to which we can all relate. This is central to the strand of hope in the book because it humanizes the people living in the Dom community. We must, after all, see them as people even as their neighbours treat them worse than animals, which in this case is what happens as the girl is from the Brahmin caste and the boy is a lowly Dom. After may trials and tribulations, the relationship manages to endure but not before the family is broken.

Iyengar also exposes the hierarchy in between the top and bottom caste, demonstrating how the wood sellers who sell the wood for the cremations make a lot of money playing upon people’s emotions, and selling various types and amounts of wood as well as decorations for the cremation. The bargaining process around a cremation is described in striking detail.

Iyenger also writes of the scavengers who dive in the Ganges for ornaments that may have fallen from ash or a partially burned corpse when being immersed in the water. She remarks on the irony that this is considered unskilled labour but it no different from what a diver does to recover evidence for the police.

It is the Doms, at the lowest end of the totem pole, though necessary for the rites to take place, who suffer the most. Some of their accounts are haunting, “Do you know the sound of blood simmering beneath skin,” says one to Iyengar. Another recounts a dream he had of a woman he had just cremated reaching out for him. It is for this reason that the Doms do Nasha, which is the use of some kind of intoxicant, either alcohol or drugs or both, in order to deal with the constant that is death in their daily surroundings.

Each Dom burns between three to five bodies a day earning between Rs. 200-250 per corpse. It is a low wage but a liveable one. And, some Doms talk with pride about their work, for it is they who facilitate the liberation of the soul from the body, something no other profession can boast to do.

In her myriad of stories of the process by which human remains are disposed of and religious rituals are conducted, and the people who are part of this process, Iyengar has created a lucid account of a little known and fascinating world – one which is still not inhabited by modern India, in which caste hierarchies dominate and the dead drive the work of the living.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine