Ghosts of Calcutta: A Retrospective

“His back turned to me as he yanked a glass window pane shut, I watched his sense of loss manifesting as fluid, uncontained by his apparitional reflection sliding with the movement of his hand across the window frame. Until that point, I had seen him cry only once before, years earlier when his mother had died.”

This is an excerpt from a series by S.B. Veda to be published in various forms, the first of which was read at Worlds Literary Festival, Norwich, June 17, 2014 and is published here.

_________________

Do you believe in ghosts? I do. Not the kind about which we read in horror stories: spirits of the dead doomed to inhabit places; my ghosts are of a different variety, for I see the spirits of dead places inhabiting souls of the living – cities alive in peoples’ minds, trapped in memories, travelling with them from place to place, hoping to find comforts from the past lurking in even the most remote corners of their present.

I write this piece from a place officially called Kolkata since 2001 – and to which those of us who remember the culture and legacy of the space it occupies are prone to refer to as Calcutta. This is done out of necessity, lest we forget what it means to us.

Understand this: I do not inhabit that city; rather, it inhabits me.

It was something I did not realize until I came to live in India, for I was not born Calcutta – nor did I grow up in there. And, save for periodic trips to Calcutta around Christmas time, I did not reside there until 2011, though people often ask me what it’s like to have ‘come home’. It’s an ironic question because I have not come home to a place I recognize as home but it does feel familiar and holds comforts that I cannot find elsewhere.

My connection to the city begins with my parents, who grew up in Calcutta, went to college there, and came into their own while living there as young adults. In my father, especially, Calcutta helped form his character, and he was molded, in turn, by its culture.

My parents were at college in Calcutta during a vibrant period: legendary film-maker, Satyajit Ray was winning awards at Cannes and Venice; the name Bose was known for revolution and Bose-Einstein Statistics rather than speaker systems; and conversation in the city was influenced by a vibrant intelligentsia, who could regularly be seen at Coffeehouse, located not far from my father’s home. This center of culture was where he and his friends, my mother among them, could be found absorbing the stimulating atmosphere after class. It was a time of cultural renaissance – the second one in modern times, its predecessor taking place during the British Raj in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The thoroughfare of Calcuttans was dynamic with the very ground shifting beneath their feet as the masses raced forward. Issues such as land reform and wealth re-distribution, began to dominate public debate, and far left politics emerged as a challenge to the ruling Congress Party, the party of independence, which had evolved into an instrument of oligarchy in economics and dynasty in politics.

My father’s first job out of university was as a Government Officer at a time when such posts carried great prestige (indeed, though somewhat diminished they are still highly coveted). He wrote speeches on the redistribution of land and wealth for a young Marxist minister, who would go on to become Chief Minister of West Bengal and the longest serving such premier of any state in the Republic of India. The Marxists’ rise to power was an event that my father mainly watched with interest from afar. He followed their progress first with optimism, and later with disillusionment as corruption became the state religion. During this time he became a portrait of disassociation: his mind and his heart were back in Calcutta, so he created a microcosm of his childhood within the four walls that we inhabited in London and later, Ottawa.

Baba (or Dad as I sometimes called him) was soon keeping pace with his peers in the North American corporate rat race, so long as he could return from work each evening, to the Calcutta in his home. He returned, too, during annual vacations to his hometown and the decaying house where he had been raised near the Coffehouse ‘Adda’ of college days. I became (at times an unwilling) passenger on these voyages, both the physical and metaphysical.

In retrospect, it seems quite natural then, that I should fall in love and marry a girl from Calcutta. Without digressing into the details of our story, we both became convinced that Calcutta, more precisely our absorption of it, stood as one of the key elements around which we could so easily relate. So, after living for two years in Canada, my wife and I decided to relocate the city, which had been synonymous with our serendipitous union.

Upon arrival back to Calcutta, my wife was surprised at how much the metropolis had changed even in the brief span during which she was away. Three years on, I feel that the Calcutta, which I knew, that anchor of culture on to which I used to grab on during the daily tumult of crossing the border of our Eastern home and the larger Western World, is dissolving into ether – no longer a tangible presence.

While I do not wish to give a history lesson, to understand the phantom citadel that is Calcutta, and by extension its ghosts, one must have some sense of its genesis. Although ancient ruins some 35 km from the city’s center indicate that people inhabited the ground since ancient times, the city of Calcutta did not exist until arrival of British in the late 1600s. At the time, three villages sat where a city would stand: Sutanati, Govindapur and Kolikata – namesake for its successor. Its inhabitants were mainly weavers and fishermen, and it was ruled by Nawab Siraj ud Dulah, whose mostly autonomous state fell under Mughal Suzerainty.

The right to levy taxes was held by Hindu landed gentry, and they made it their business to be close family of the Muslim ruler. Key among them, the Sabarna RoyChowdhury family, sold their possession taxation rights to vast parst of the area to a British trading house called The East India Company, and soon after the British Raj was born.

Between 1797 and the early 19th century, the Governor – Richard Wellesly was his name, ordered the draining of the marshes in Govindapur and Sutani, and built institutions, the great buildings that stand today as landmarks: The National Library, Writers’ Building, and Howrah Station among them.

They cultivated a class of literate Bengalis to write the laws, and the many documents required to administer them. Hence, their seat of power, the center of administration even today – Writers’ Building, is named for it. This class of elite needed to read and write in multiple languages but principally in the English. They were known as the Babus.

When the Babus realized that they were essentially running Britain’s Indian Empire, a national consciousness set in: Why shouldn’t they rule the country, too? The first nationalist organization was formed in the city, and Calcutta became a hotbed of revolutionary activity at a time when writers and thinkers inspired a new generation of literate nationalist Indians. Included among them were Asia’s first Nobel Laureate, the writer, Rabindranath Tagore, the rebel poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam, nationalist author, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, and philosopher and founder The Ramakrishna Mission, Swami Vivekananda – all of whom called Calcutta their home, at least for a significant period. This was the first modern renaissance, Western in form but Eastern in substance.

By 1911s, a now firmly established British Empire responded to Calcutta’s revolutionary movement by moving their capital from Calcutta to Delhi from where the ousted Mughals had previously ruled. Many important institutions and industries remained in Calcutta but they were slowly dismantled after independence paradoxically to either undo or follow all things British. However, bricks and mortar remained, which explains why a small section of Calcutta – ‘White Town’, it used to be called, remains an oddest approximation of London I have seen outside of England’s borders.

Much of Independent India’s narrative has been shaped by a contest between history and nationalism; in such conflicts, nationalism tends to win-out. This is as true of Calcutta as any place. So, not long after the turn of the current century, during a period when the people of other urban centers were reclaiming their ancient names: Bombay became Mumbai, Madras became Chennai, and so on – Calcutta became Kolkata.

Unlike other cities which had existed in antiquity, the name Kolkata has had no such history: the whole of its space was, until 2001 ever only known as Calcutta, leaving many to question, where is the homage to Sutanati, to Govindapur in the name Kolkata? Where is the connection to the past? I have come to believe Kolkata was a re-invention by politicians of the day to distract from broken promises and unattained goals. Perhaps (if unwittingly) it was a way to claim ownership over both progress and error since independence.

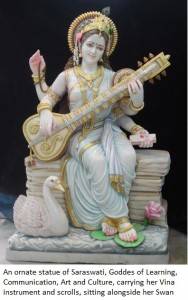

But enough of history and politics – let’s get back to the ghosts: I first saw one in my late twenties. Our annual trip to Calcutta had gone a little late, and crossed the date of the Festival of Saraswati, Goddess of learning. I remember seeing the idols of the Goddess being made and sold on the street. Many of them elegantly depicted her, sitting with her swan, in a white Sari. She is depicted holding an instrument made of wood called a Veena, its long hollow neck, lined by several strings, jutting out of a large gourd-like base, designed to resonate deeply.

My father, a religious man (at least, ostensibly) who placed highest of value on education, made sure that the ritual around this festival was strictly and respectfully observed in our Canadian home, each year. It was a ceremony, which he often performed, himself. To this day, I can still hear drone and rhythm of Sanskrit incantations uttered by him with intensity and concentration: “Om Sarasatai Namah. Om Sarasatai Namah. Om Sarasatai Namah.”

My father, a religious man (at least, ostensibly) who placed highest of value on education, made sure that the ritual around this festival was strictly and respectfully observed in our Canadian home, each year. It was a ceremony, which he often performed, himself. To this day, I can still hear drone and rhythm of Sanskrit incantations uttered by him with intensity and concentration: “Om Sarasatai Namah. Om Sarasatai Namah. Om Sarasatai Namah.”

Yet, on that winter’s day near the turn of the 21st century, the sound of the mantras was interrupted by a loudspeaker, playing the popular western hip hop dance hit, “Who let the dogs out” – and this too, over and over again. The sound of it, the reverberation of the thunderous base, the turbulence of the blustering words, “Who, who, who, who let the dogs out,” violated the sacred space, he had created in his mind for the Goddess, owing to years of experiencing this day in the same way. The result was an obscenity, an anathema. It drove my father mad.

His back turned to me as he yanked a glass window pane shut, I watched his sense of loss manifesting as fluid, uncontained by his apparitional reflection sliding with the movement of his hand across the window frame. Until that point, I had seen him cry only once before, years earlier when his mother had died.

The childhood memories were soon streaming off of him, two estuaries beneath his eyes, his regret flowing into the sea of new and unwelcome experience. In Canada, he had been trying to preserve a ritual that had been observed in his home since boyhood days – but in the Kolkata of the 21st Century, it had just become another holiday. Dance, get drunk, get laid. Today, it resembles valentines more so than an occasion to honour learning and creativity.

He has never returned to the city during any Hindu festival, since. His most recent trip occurred during Christmas, last year. He can only come back, it seems, when experience fails to defeat his idea of the city. And then, he leaves.

***

I have my own ghosts, too. I was introduced to this city during a period before the beginning of memory, at age six months when my parents brought their first born home from London, England – my birthplace – to show me to the extended family. I’d like to think I soaked in some of the culture of Calcutta, even then – but surely since. In fact, so much of the adsorption remained that I returned there on my own to study my culture in my early twenties.

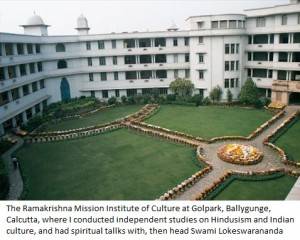

I studied Hinduism at The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, staying at their International Scholars House, during summers in Calcutta. The institute is located on an island of greenery in a sea of concrete, metal and glass at one of South Calcutta’s busiest areas: a place called Golpark where, at a roundabout, the statue of its founder, Swami Vivekananda stands prominently, perhaps watching the movement of souls. He would have watched over me, then, just as I would have wanted to take in some of his wisdom.

There, while contemplating the notion of renunciation, I became interested in the different paths to divinity outlined in Vedic texts.

I was particularly drawn to the idea of union with God through Karma or work, the concept of working for its own sake, without laying ownership to the fruits of that labor – a form of renunciation that did not involve removing oneself from active life. The practice is called Karma Yoga, and I was first exposed to it when reading the Bhagavad Gita, and later in the wrtings of Vivekananda.

I was particularly drawn to the idea of union with God through Karma or work, the concept of working for its own sake, without laying ownership to the fruits of that labor – a form of renunciation that did not involve removing oneself from active life. The practice is called Karma Yoga, and I was first exposed to it when reading the Bhagavad Gita, and later in the wrtings of Vivekananda.

During morning chats with the head of the Mission, Swami Lokeswarananda, I asked him how an ordinary person could reach such a state of even-mindedness that success and failure could truly be viewed as the same impostor, as Kipling, had so eloquently put it in his poem, ‘If’, (one of history’s great ironies, by the way). He advised me that Karma Yoga was best practiced when the aspirant is engaged in activity that is in keeping with his own nature, else he risks it becoming a chore. He said, one ought to take pleasure in the doing, embody the action of acting rather than being preoccupied by the result. I could see the application of it in artists, musicians, some academics, and certain pro athletes – but could it happen at a mundane job? Surely this was an idealistic fantasy! In that sense, I questioned its practicality, and wondered whether anyone had observed it in the labor class? I could scarcely imagine a sweeper’s broom bringing him closer to Nirvana with each pass.

I was treated very well during this period, and thought very well of myself for coming to Calcutta to carry out these independent studies; after all, how many of my generation actually cared about Indian culture or took the time to understand Hindu philosophy on a deep level? I felt a little superior, I must confess. And then I met the Muchi of Golpark.

Having tracked some kind of sticky substance on my shoe, the scientific name for which I believe is ‘crud’, I asked some locals where I could get it cleaned, and was told about a cobbler or Muchi, who sat on the footpath of the Golpark roundabout, plying his trade in the gaze Vivekananda’s statue.

It didn’t take me long to find his stall as so many people knew of him, and I soon found myself peering into his bony face, which hung under his dark hairless scalp. He was sitting, one bony leg crossed over another, reading a book.

Upon seeing my predicament, he told me to remove my shoes and step on a piece of cardboard. The idea of baring my unstained feet, in the middle of a dirty street corner and stepping on a surface that, no doubt, many others had placed their filthy soles, was something I found intrinsically repulsive. Naturally I protested, telling him it wasn’t a complicated job – and all he merely needed to do was wipe the substance off with a cloth and some kind of cleaner.

Calmly, he holding his pinkish palm up to me, he said, ‘Yah mera dharma hai.’ Please, this is my job – but the word Dharma didn’t just mean job, it meant divinely inspired job, sense of purpose or duty; even, ‘this is my religion.’. I was taken aback: How could I now refuse? After all, he was saying his divine purpose in life was to clean my shoes.

I watched the man, size up the stain, then slowly work the sides of the soiled shoe – first with a dry cloth – then mixing some tea-colored solvent with just enough water, not wasting a drop, he moved the cloth back and forth over it. After he finished one shoe, he did the other. It was different formula with a different sequence but he managed to make them look exactly the same – all without shoe polish. He spent roughly half an hour in the burning sun on this mundane task when he could have easily gotten out of it by following my now admittedly arrogant demand.

As the Muchi handed me back my shoes, I asked him how I had to pay, to which he replied, ‘ten rupees’. I was so impressed, I tried to give him twenty – after all it was less than a dollar for me, and he deserved so much more. He politely declined asking me why I should pay more when he had done nothing extra. I told him that I wanted to reward his professionalism.

He flashed a toothless grin, and said something that stunned me: ‘I know who I am. Your money won’t inform this to me.’

In a land where the law of paying tribute or Bakshish ruled supreme, he was content simply in the doing.

It was at that moment that I realized that I could not say the same to him, for my job was not my divine purpose in life. I did it for money. Did that make me a whore? No. But it didn’t make me a Karma Yogi, either. I knew, too, that I had found, at long last a laborer, who worked simply for its own sake without laying claim to the fruits of his efforts. More importantly, he seemed to have found some higher meaning in the doing. I understood in that moment that, even unpaid, I should take up the pen, simply because it was in my nature to do, and was something for which I made too little time. It was a lesson, which, in time, I forgot after my return to the rat-race of working life in Canada only to be recollected and followed when I came to spend more time here. The day I started to write not for money or accolades or in search of fame, but for its own soul-enriching value, I became a writer.

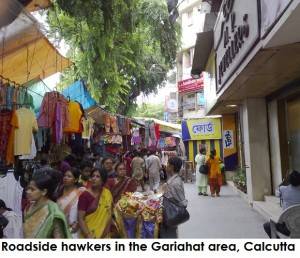

I have looked for the shoemaker many times since but have never been able to find him, his spot occupied by another, his legacy unknown by the young merchants and laborers at Golpark. I can only conclude that today, he and his ilk are long gone from the sidewalks of Calcutta where the hawkers sit, many of whom try to cheat their way to a daily wage. In the meanwhile, he has become a ghost, haunting my retrospection of this place, and reminding me of what I loved about a city that truly could represent greatness within the mundane.

***

I think of the Muchi during a sweaty afternoon as I research a piece I am writing on a different intersection in Gariahat, a stone’s throw away from Golpark, where roadside markets thrive. I watch as a dark suns-soaked man, squeezes dye made from an herbal concoction in a floral pattern, out of a plastic dispenser. It falls on the delicate arm of a young bride to be, named Sweta, a statuesque Punjabi, pretty with a milkish complexion, and large eyes lined with the black paint of Kajol. Her nose is an elegant, if excessively pointy, hanger for a gold ring, which rests above her full lips.

I ask the young woman if she is getting married. Nodding, she tells me her groom, Ashok, is Bengali, adding with a smile that her husband, whom she met in her engineering class at college, had to promise to give up eating meat before her father would consent to the marriage. In turn, he promised his mother that he not stop eating fish just because his bride came from a family of vegetarians.

Neither will be the wiser, for the couple are planning to move to Switzerland after marriage, where Ashok has been offered a job. Years later, I wonder how Sweta will view the city on a visit through the eyes of a Swiss resident.

I ask Shankar, the man applying the dye, called Mehndi or Henna, how long the tattoo will last. He says fifteen days, then it will take another fifteen days to fade off. This makes sense to me as I have seen the bruisy mess that is fading Henna.

Shankar is keen to assert that applying Henna is an auspicious act, representing new beginnings. He also says it is one the few things that unite the two major religions in the city, Hinduism and Islam in that it goes back not only to the ancient Vedic period of Hindu ritual but has also been used extensively in the Arab world as a form of fashion, to accentuate female sensuality after marriage.

Shankar is keen to assert that applying Henna is an auspicious act, representing new beginnings. He also says it is one the few things that unite the two major religions in the city, Hinduism and Islam in that it goes back not only to the ancient Vedic period of Hindu ritual but has also been used extensively in the Arab world as a form of fashion, to accentuate female sensuality after marriage.

Sweta whose foot is being ‘Henna’d’, now, smiles, nervously at the remark, perhaps realizing she has exposed a section of her leg that stays covered most of the time. In India, modesty and sensuality compete in the in how women are and wish to be perceived.

I ask Shankar if this is a family tradition; “no,” he replies, his father was a farmer, he says, adding that he had to work his way up, for many years, to this prime location at the corner of Rashbehari Avenue and Hindustan Park. How did he obtain this coveted position, I ask, knowing that such stalls both in demand and unsanctioned by the municipality. His response is nonverbal, smiling with head rocking from side-to-side. ‘It takes money,’ mutters one of his underlings to another boy who sits on a red stool beside the stall. They chuckle, knowingly.

Moving on, I wonder aloud about the demand for his trade as I know that in the state of West Bengal, where Calcutta is located, marriages traditionally use turmeric paste in the ceremony instead of Henna. I recall being ambushed by a group of female relatives with turmeric paste on the day of my wedding- a tincture of yellow, that would also be used on my then bride to be to make us glow before the ceremony. My bride coloured had elaborate red designs called Aalta, painted on her fingers, and hands, the same on the soles of her feet, for applying Mehndi is not traditionally a Bengali practice.

Shankar tells me business is booming, that Mehndi has become very fashionable in this Bengali speaking state, despite it not being traditional. In fact, in the line of six young ladies waiting for their turn, I hear mostly Bengali being spoken.

In Calcutta, such conversations are far from private: A middle-aged sari-clad woman browsing sandalwood ornaments at a close-by stall announces that Shankar’s economic ascent is due to the decline in Bengali culture. A Bollywood hit blaring on an unseen speaker punctuates her point. Modern Kolkata’s homogenization into a generic North Indian city is apparent to anyone who has known the old Calcutta.

I turn back to the young ladies, asking how many of them are getting arranged marriages. Only one raises her hand – a young girl named Padma, also pretty but much shorter than Sweta. Her long black hair sways around her knees as she looks to see how many hands are up. Her widens her eyes in disbelief that she is alone in the group. Her English is not strong, and she prefers to speak Hindi, which my wife translates for me, saying she is a Marwari whose whose family migrated from Rajastan to Calcutta generations ago as traders.

I turn back to the young ladies, asking how many of them are getting arranged marriages. Only one raises her hand – a young girl named Padma, also pretty but much shorter than Sweta. Her long black hair sways around her knees as she looks to see how many hands are up. Her widens her eyes in disbelief that she is alone in the group. Her English is not strong, and she prefers to speak Hindi, which my wife translates for me, saying she is a Marwari whose whose family migrated from Rajastan to Calcutta generations ago as traders.

I am aware of the community of merchants from the Marwar Region of South Western Rajastan, who have flourished in their many commercial endeavors since arriving. She is all but nineteen, and says that in her family, brides marry young in family alliances, which are made to maximize profit; her husband’s family is in real estate, and hers sells furniture. The marital deal seems something of a a vertical integration of the businesses.

A bespectacled Bengali girl standing behind Padma holds a mouthful of smirk, which I cannot help but notice, asking her name. ‘I am called Jhinuk’, she informs me, elaborating that these days, among college-educated girls in Calcutta, only those who can’t socialize properly or come from extremely conservative families get arranged marriages. She says most kids date, often in the open,. Even when romance is secret, it is typical for families to come to accept the matches, even inter-religious ones.

I find this hard to believe. Still, when I arrive home for lunch, I am confronted with evidence that seems to support what smirking Jhinuk has told me. I arrive to the scene of our cook, who has been absent for several days, sobbing to my wife about her daughter. Between choking on certain words, she tells us that the girl has run off with a boy from a neighboring village.

The woman, in her mid-thirties but looking much older, travels around two hours each way by train from one of the small hamlets south of Calcutta to work in the city. It is a hard life, and she has many mouths to feed as her husband drinks too much, and cannot hold a job.

She explains that they had gone to a wedding reception of a distant relative, and her daughter disappeared. After much searching, two days later, she found out that the girl had eloped with another wedding guest.

She seems especially upset because the boy is a rickshaw-puller of little means from a poor family. And, they are not Bengali. They hail from neighboring Bihar, having come to West Bengal more than a decade earlier in search of shelter, when Bihar’s borders were virtually lawless.

My wife, a lawyer, asks if the girl was abducted, and quotes the sections under which complaints can be lodged at her local police station. The woman shakes her head. She says she already gone to the home of the in-laws, and was told by her daughter that the two had been planning this for some time. She is still reeling from the shock but, I can hear a quiet chord of relief in her voice: one less mouth to feed, one less daughter to marry-off; one less problem with which to cope in her busy life. The sobbing before my wife seems more drama than complaint.

Even in the villages surrounding the city, the young are empowered. The voices of elders can still be still be heard but the words are seldom heeded. The Calcutta in which the wishes of elders were respected has metamorphosed into a Kolkata where young people feel free to do as they please regardless of familial consequences.

***

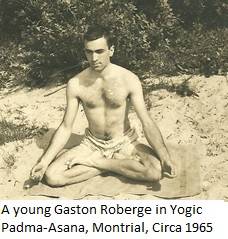

Later, I visit an old interview subject, into whose forty year old first book, I am trying to breath new life. He is an iconic symbol of West and East existing in the same space: Professor Gaston Roberge SJ, 78, a Canadian Citizen and Jesuit priest, and former head the Communications Department of the prestigious St. Xavier’s College, now retired.

Father Roberge is a bit weary this afternoon, and it shows in his ginger movements and heavy breath as he escorts me to his residential chamber at the college. White hair is pressed against his scalp. The large lenses of his specs, which look like the bulging eyes of a fly, dart from me to the path in front of us and back to me as we walk and talk. The flesh on his once athletic frame has become deposited at his abdomen. His erstwhile erect stature bears the bend of a young tree growing towards a splinter of light piercing a forest canopy. But, he is neither a sapling nor rotting timber. He is vibrant, active, alive – and young at heart.

Known as the father of film studies in India, Gaston Roberge founded Chitrabani, Eastern India’s first communications institute, and remains a prolific author of twenty-four books.

Known as the father of film studies in India, Gaston Roberge founded Chitrabani, Eastern India’s first communications institute, and remains a prolific author of twenty-four books.

A student passes him. “Morning father”, says the boy. The priest smiles and nods.

He turns to me: “Is it still morning for you? It is for most people over here. Early afternoon is a mystery. I never know whether to say good afternoon or good morning.”

I nod, replying, “Perhaps you should just say ‘hello’ or ‘good day”

“But what if I am having a bad day,’ he counters with a grin,’Would God forgive the lie? I’m a priest, after all!”

We laugh. His sense of humor is a timeless aspect of his character – one he and those around him are privileged to enjoy.

We are both Canadian citizens, and in his office, I tell him that, today, I miss my home, there. He says he seldom thinks about Canada, and describes a life story that is compellingly different from that of my father’s. Born in Montreal, to a newly widowed mother, he came to Calcutta more than five decades ago, and basically never left. He seems to carry no ghost from Montreal with him.

He is often asked why he would choose to live in a wretchedly poor, crowded and dirty place like Calcutta when he was born and raised in such a rich and clean country. In consequence, he has a well-practiced answer. “Fascination,” he says. He tells me as a young Jesuit volunteer in Montreal he was enticed by the spirits haunting his uncle, a Radar Engineer who had been posted by the Royal Canadian Air Force in South Asia. The boy, Gaston, who was a regular visitor to his uncle’s place became enthralled by stories of the east recounted dramatically by his mother’s brother.

“To put an exclamation point on it,” says he, “There was a stuffed mongoose on a side table, and a tiger skin on the floor!”

Notwithstanding my shock at the existence of such trophies from the wild, the sale of which would be illegal, today, I could understand well how the boy, Gaston might become hooked on the prospect of going to a land filled with such wonder.

He smiles and says it took him years to get here. When he got his chance, he prepared for the mission by first learning Yoga from the Montreal Chapter of the Sivananda Society, showing me pictures of his younger incarnation. In one he is sitting in the Lotus position, Padma Asana; in another, he does a shoulder-stand.

“I was given five years to decide if I wanted to stay (in Calcutta). It took me all but five minutes to choose to make it my home,” he says

He describes his time staying with a Hindu family in Calcutta, absorbing as much of the culture surrounding him as could be taken in.

He describes his time staying with a Hindu family in Calcutta, absorbing as much of the culture surrounding him as could be taken in.

“I was ‘enculturing’ myself”, he proclaims, “When one is on a mission, one must not only spread the word of God but one must also try to learn more about God. That is the way I see it, anyhow. What better way to do so than through his children, regardless of the religion they follow – and the people were so Godly. Another might take a different view but I felt that it was essential to my cause.”

He mentions being exposed to The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna Paramhamsa, the famous Hindu Sage who officiated at the Kali temple of Dakshineswar, located some 15 km from Calcutta, to whose works he became exposed at the time, adding that he appreciated the mystic’s use of parable.

He soon recognized in him the calling to the priesthood, and decided to take his vows, and he reflects on this crucial juncture of his life path, telling me about the trip his mother made, coming to Calcutta to see him ordained. His gaze now filled with nostalgia, he reveals that, save for a brief posting in the Indian city of Pune and two years as Vatican Communications Director in Rome, he spent the remainder of his life as a monk on the campus of St. Xavier’s in Calcutta.

I remark that he is truly a Global Calcuttan. He likes the label, and smiles in agreement.

He says his connection to Canada has slowly diminished with time.

“Initially, I missed my mother, my sister, friends from the Society of Jesus,” he confesses, looking up at the ceiling, “but one by one, God has taken them, and with it my interest in going back.”

I ask him when he was last there, and he tells me of a bewildering return trip taken around a decade back, “Everything was so American,” he says “I could not recognize our small parish on the edge of Montreal; though people spoke my language, it seemed very foreign to me, like I had gone to a foreign country. So, I was glad to return home to Calcutta.”

These days, he feels more Indian than Canadian, elaborating that some years back, he considered changing his Citizenship to Indian but was dissuaded when he realized that the Society of Jesus would lose the small pension, which he received from the Canadian government.

He gives me the manuscript of his latest book, and signs it, writing the word ‘Fadar’ beside his name in parentheses, the way father is pronounced by the locals, adding the moniker ‘Global Calcuttan’ to it.

Gaston Roberge seems a man with a firm sense of his place in the world. He has embraced circumstance and change just as my own father has had to begrudgingly accept it. He is a priest, who has exorcised the spirits of the departed metropolis of his birth. In that there is a certain freedom; and I observe with admiration, the ease with which he navigates a place where the residents consider him to be a foreigner while his own sense of identity is firmly ensconced by city of Calcutta.

***

As for me, I have come to understand my identity as being born of many mothers. And so, I long for different things at different times: from the sound of ‘mind the gap’ to a large plate of batter-fried haddock as I glance the sight of modern and medieval architecture existing in one space through a London window-pane; the smell of fresh warm bagels from Montreal that are so delicious they need not any topping, the sight of maple leaves turning color in autumn, and catching snowflakes on my tongue during Ottawa’s first snowfall; the ‘swoosh swoosh’ sound of the Calcutta street sweepers waking me up in the morning, followed by the call of the local fish seller, announcing the morning’s first catch. I am a man, today, of many homes, and I realize, I ache not so much for the physical sensations of them but what they evoke in me: moments in time, parts of my life, which I hope to relive for the joy and comfort they bring me.

I realize, too, that one cannot go back. The desire to do so can be injurious to the soul as exemplified by the sadness my father feels of a life that has passed him by. I conclude that we are bound to move forward in much the same way as Father Roberge has done.

My thoughts turn to Sweta: in a few years, I wonder if, on a visit from Switzerland, she will reflect back on how things were, when it was so safe and easy for her to get her arms painted on the sidewalk of a busy intersection in the city. She may see the floral patterns on another girl, and recall the tingle and wet of the paste on her own arms as she prepared for her marriage. She may even remember the curious Indian-looking foreigner asking her and the other young ladies questions about their lives as they all waited in line to be ornamented for change.

And, I will become one of the city’s ghosts – not of my Calcutta but of Sweta’s Kolkata on the day when it becomes something and new and different for her.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

Brilliant article. Echos my sentiments, exactly. I loved the part about the wise shoemaker. He truly is a ghost, today! Keep it up!

Wonderful glimpses of the city that was and that is. Excellent!

Reading this article brought tears to my eyes. I too feel the legacy of a great city is fading. The metaphor of ghosts is quite apt. Beautifully written, and evocatively described. Great piece of feature writing!

Fantastic article – makes me want to see the place myself before it dissolves into history. Keep it up!

What a city! I never thought of Calcutta in that way. Makes me wonder why it isn’t a more popular destination to visit for those who really want to know India. Loved the article!

Calcutta vs. Kolkata – who knew? Now, after reading the article, I feel like I know, and have traveled there in my mind. Well done!

Calcutta was a great city! Thank-you for keeping the culture of this place alive. Let us all be haunted by the Ghosts of Calcutta!

C’est magnifique. I was riveted from the first paragraph! A gem on the web. I long to read more.

Makes me nostalgic for the city. great content and pic. I’m fast becoming a fan

I was impressed by the elegance of the writing, and the clarity of observation. This should be the stuff of literary magazines. Write on, SB Veda!

Brilliant! It’s so rare to find content of this quality on the net. Keep it up!

Wonderful piece. I loved the memories of Saraswati Puja, the Muchi of Golpark, Mehndie hawker, and Father G. Terrific story telling. Makes me momentarily thankful to be a Calcuttan in the thick of the daily struggle. Fantastic!

This quite nice reading but Kolkata remains backward place far behind Mumbai, Bangalore, delhi. it is wy all the successful bangalis are coming out of da city to other place

Fascinating.I always longed to be in Kolkata,but it was not possible.You style is brilliant.

I read a lot of interesting articles here.

Thanks for your details you supply by way of this fabulous website, My partner and i has been served to find the facts We was looking for and also need.