Wimbledon Goes Global in Calcutta

“It’s nice to be able to combine a high-end tournament like the RTW Masters and coaching with outreach activities like Magic Bus to do good in different ways.” – Dan Bloxham, Head Coach, The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club

Amidst growing isolationist movements, worldwide, how the Road to Wimbledon is stretching across borders to find future champions and improve livelihoods in far flung places

SB VEDA

<CALCUTTA>

With the litany of obituaries for globalism published after Brexit and the US election result, sixteen Indian girls competing at the Calcutta South Club for the chance to play at Wimbledon proved that through sport, at least, we may well see a resurrection.

Thousands of miles away from the lush greens and creeper covered boundaries of Wimbledon’s Centre Court, India’s top sixteen girls were all smiles on the freshly cut lawns of the Calcutta South Club, knowing that their dreams to play on ground sacred to the sport of tennis could be within reach. For the winner and runner-up of the Road to Wimbledon Masters, played at the South Club, are wild card entries to the UK 14 and Under National Championships to be played at none other than The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club where Wimbledon is held.

In addition to the chance to play at the world’s oldest and most prestigious theatre for tennis, the Road to Wimbledon (RTW) program offers valuable interaction with coaches sent by the All England Club to impart lessons on how to play on grass – this as the junior circuit offers diminishing opportunities to gain experience on the surface.

WIMBLEDON’S GLOBAL OUTREACH

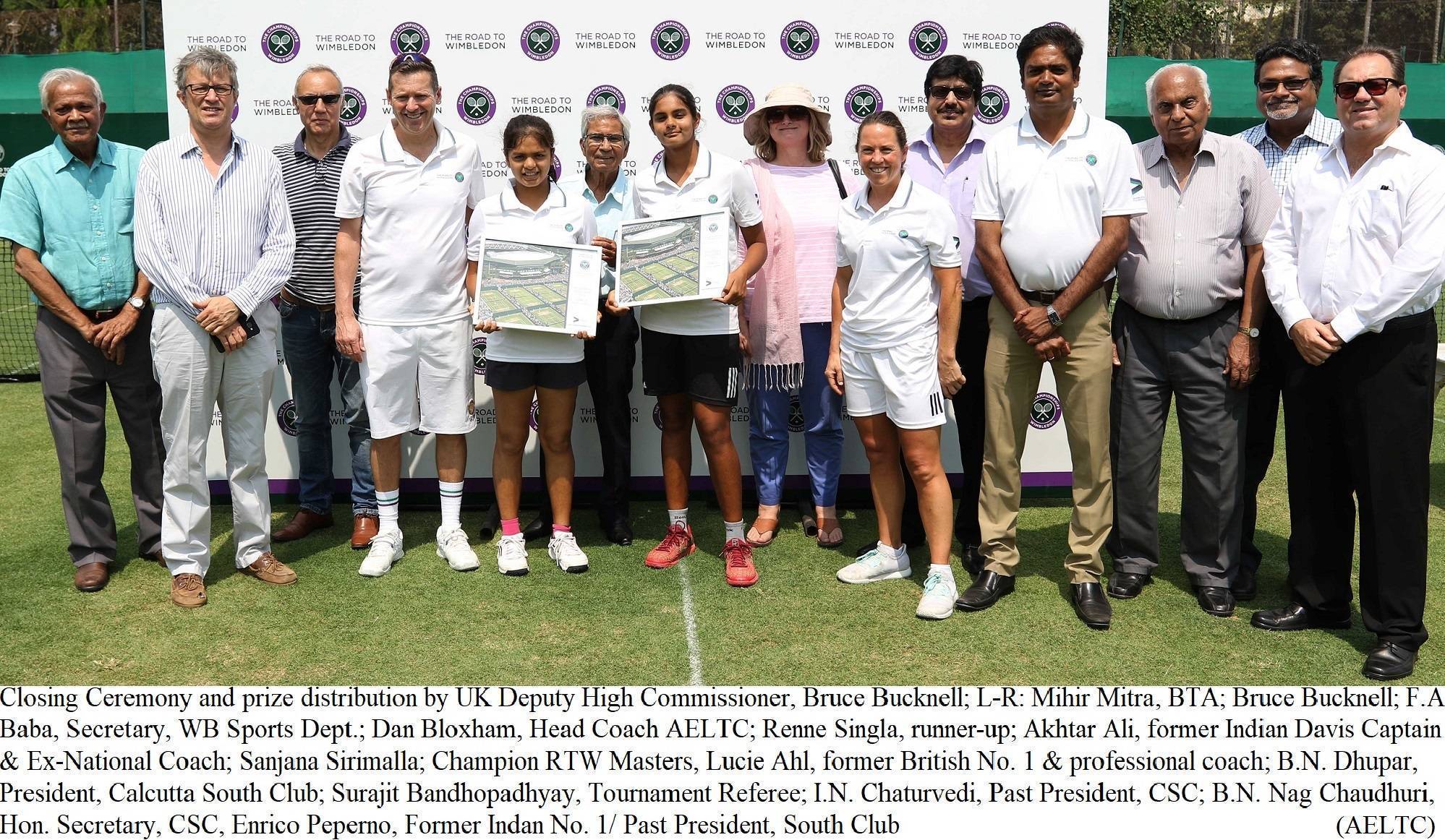

Having evolved from a regional juniors program based in the UK into an extensive global outreach, The All England Cub takes RTW seriously, sending Head Coach Dan Bloxham and former British No. 1 and star coach, Lucy Ahl to Calcutta. Joining Rolex Tennis Ambassador, Vijay Amritraj at the Gymkhana Club in Delhi, to focus on the RTW Under 14 Boys Masters, the coaches also participate in outreach events such as Magic Bus, which is funded by the Wimbledon Foundation to educate disadvantaged kids in hygiene, nutrition, and the importance of education.

Magic Bus aims to ensure that every disadvantaged child can access formal education, finish school and is positioned to achieve a sustainable livelihood, developing the right life skills to become economically independent. Notably, the program uses tennis to eliminate gender bias among the kids and trains community youth leaders to work with parents and other authority figures to reinforce the teachings.

“It’s nice to be able to combine a high-end tournament like the RTW Masters and coaching with outreach activities like Magic Bus to do good in different ways,” says Bloxham. He also lauded the Bengal Tennis Association’s outreach at the Calcutta South Club, the gates of which were swung open to children from all walks of life, including their participation in events and observing the coaching.

The RTW coaching programme emphasizes how to play on grass, distinguishing these lessons from what the children already get from their own training at home. “A lot was about giving the kids an introduction to grass and the contrasts between clay and hard courts,” said Ahl on Friday. “We’re trying to get the girls to keep the ball low, and use the slice more as well as, with the low bounce on grass, getting the player’s physical position lower to the ground,’ Ahl added. These adjustments are key to winning on the soft turf.

Indeed, with so few lawn tennis courts left in India, the next time the winner and runner-up are likely play on grass is at Wimbledon. Understanding this, the coaching clinics saw enthusiastic participation from the girls.

SUCCESS NOT JUST A FUNCTION OF TALENT: COACHES

Impressed by the great hands of the talented juniors competing at the tournament, Bloxham warns that talent can be a double-edged sword in competitive sport. “Sometimes players with great hands don’t have as much of an interest in moving, and the footwork lags because they can hit such great shots from different positions – so talent can have a good and bad impact on player development,’ he adds.

Ahl concurs. “The girls are really talented. Those who maybe aren’t as talented and can’t hit wide balls from any position, really need to get behind the ball, so they’re more focused on footwork and fitness. But this pays off as one moves forward…if you get in the best position because of your footwork, you have more options to win the point,” says Ahl

Roger Federer, Raphael Nadal, and Martina Navratilova exemplify the ideal of unreal talent matched by outstanding fitness and footwork.

Sujoy Ghosh, COO of the Bengal Tennis Association agrees that success is not all about shot-making – especially in singles. Lack of fitness parity has been an issue that has prevented the development of world-class depth in the singles game in India, says Ghosh. “We’ve got a lot of great singles players at the junior level but when faced with bigger and physically stronger players from Europe as they progress, they hit a wall. And, these talented stroke-makers end up finding their niche in doubles after turning pro,” he says.

In doubles coverage and stamina aren’t as important as reflexes and shot-making skill, which Indians have in abundance. In fact, in recent years, so many world-class doubles players have hailed from India, it seems a shame that we don’t see Indian names among the top 100 singles players on either the men’s or women’s side of the game.

It wasn’t always so. During a golden era in tennis history, Ramanathan Krishnan had reached the semi-finals of Wimbledon twice and rose to a career high of no. 6 in the world. His son Ramesh had a career high singles ranking of no. 16 and had made the quarterfinals of Wimbledon and the US Open in singles. And then there’s Vijay Amritraj: the now elder statesman of Indian tennis won eighteen singles titles, scoring victories over legends like Borg and McEnroe, even beating Jimmy Connors five times. Of course, these successes occurred during a different age, before advances in racquet technology and increased focus on physical training made tennis into the power game that it is, today.

CALCUTTA SOUTH CLUB – THE WIMBLEDON OF THE EAST

All the Indian greats sparkled on the lawns of the The Calcutta South Club, long known as the Wimbledon of the East for having the first lawn tennis courts in India and hosting the largest number of Davis Cup ties. It is was a key venue for coaching by the BTA and still hosts tournaments.

Founded in 1920 during the time of British Raj, The Wimbledon of the East hosted many international champions. The French Musketeers led by Henri Cochet and Jean Borotra, legendary American, Bill Tilden, and Aussie giant, Roy Emerson have all graced the greens of the South Club. Indian stars like Jaideep Mukerjea, Zeeshan Ali and Leander Paes were coached on these lawns. And, the club has been home to the Bengal Lawn Tennis Championships, which morphed into National Lawn Tennis Championships – alternating among clubs in different Indian cities, but held in Calcutta for the greatest number years.

The Calcutta South Club still boasts some of the finest grass courts in the world. Indeed, In his book, Aces, Places and Faults, Tilden wrote, “The centre court at the South Club in Calcutta is one of the best grass courts of my experience”, and legendary coach and former Davis Cup Captain, Akhtar Ali, now approaching age eighty, still coaches there. With six clay courts and five hard courts, which are constantly busy, the higher maintenance grass courts lie vacant sans nets much of the time with the general exception of member playing days. So, the sound of Slazenger Balls whizzing through the air, skidding and springing off the verdant lawns makes the Wimbledon coaches nostalgic. “We’re at home here; it feels like Wimbledon,” says Bloxham.

Wimbledon is synonymous with tennis, and for decades, the sport was only played on grass. For British Deputy High Commissioner, Bruce Bucknell, called upon to present the prizes, the pristine greens at the South Club are a source of wonder. “This is how tennis should be played,” he quips.

THE FINAL ROUND AND HOW CHAMPIONS ARE MADE

With the high velocity courts offering an ideal canvass for sensational shot-making, the finalists seemed quite at home skipping from side to side on the well-kept ground (perhaps a testament to the Wimbledon coaching). Though their places at the All England Club were assured by reaching the final, top seed Sanjana Sirimalla and challenger, Indian no. 3 Renne Singla, offered no quarter, fighting tenaciously in a match worthy of the historic battleground

After winning her semi-final match, Sanjana had announced that she wanted to go to Wimbledon feeling like a “team captain.” having won RTW rather merely qualifying by coming in second. “I’m on a mission,” she said.

Despite finding herself in all kinds of trouble against the spirited and big-serving challenger, Sanjana accomplished her mission, defeating Renne by a score of, 7-6(7-4), 6-4, in two tight sets.

Sanjana’s determination is echoed by father, Ajay who accompanied her from their home in Hyderabad to Calcutta for the event. “It is very difficult to make a professional tennis player,” says Ajay. “Tennis is the most costliest game, I feel, and all money is coming from our family. But I sold my house, so now we have no problem.”

Champion Sanjana Sirimalla (centre left) with runner-up Renne Singla (centre right) flanked by coaches Lucie Ahl left and Dan Bloxham right (AELTC)

Most would complain about the situation: parting with the family home only to be forced to rent in an area of slums for economic expediency. Not so for Ajay – and this speaks volumes for his character and that of family members.

While, Sanjana, perhaps feeling the pressure of her family’s finances, expresses frustration that her no. 1 ranking in India (14 and Under) hasn’t drawn more sponsorship interest, her father remains optimistic. “It doesn’t matter,” he says. “Whether she gets sponsors or not, she will continue as a professional tennis player and become an international tennis player. I have that confidence,” he adds.

Compared to Europe and the Americas where public courts are available and basic lessons can be had at little or no cost, public support of tennis in India is thin. And while the US college system offers scholarships to promising players, the financial obligation of supporting Indian players is almost always borne by the families, leaving many enthusiasts puzzled: “Some two decades after Venus and Serena Williams came up through the US public parks system, in India, tennis is still a sport for those with lot’s of money. This is a shame,” says one spectator who asked not to be named.

Indeed, the Singla family admits that their child would have never had the opportunity to pursue a career in pro tennis had their affluence not afforded the girl a place. “Tennis is still a lavish sport,” says Renne’s mother. “But I can afford it,” she adds with a smile as she mentions coming from a ‘business family’ with her husband being a doctor.

In fairness, the problem is already being addressed, albeit slowly in various states. In West Bengal, according to BTA Coach, Gary O’Brien, things may be changing more rapidly. “It used to be very difficult for kids to pursue tennis and schooling but increasingly, schools are becoming more flexible, allowing students time-off to train.”

“And we, at the Bengal Tennis Association, offer financial assistance through programs like our Future Kids scheme in which twelve deserving players have their tournaments, training, and equipment paid by the BTA. But you have to earn your place. We can’t offer it to everyone,” says O’Brien.

While this is a step in the right direction, India still lacks public tennis accessibility, for in a country bursting at the seams, space is a problem – and to many observers, building public courts would appear to be an extravagance in a country where so many still live in slums – or even on the street. If public courts aren’t the answer, perhaps subsidies for basic lessons would offer opportunities for the have-nots to break into a sport with costly barriers.

Three years ago, the UK started offering basic lessons for 20,000 kids for free, irrespective of their background on a first-come-first serve basis. And for those who aren’t quick enough to take advantage, a six-week beginners course offered by the British Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) course is only £25. By contrast, in most Indian clubs, when you add a registration fee to monthly lessons, which could be between ten and twenty-five thousand rupees (approx. 100 to 250 pounds sterling) in one shot, lessons are much more expensive. A program, which pays for registration could bring monthly costs in line with that of the UK. But that too would still be a stretch for many families, here.

For Sanjana’s family, their hopes and financial circumstances are pinned to the young junior player’s ascendancy. When the money from the sale of their family home runs-out, unless she is already earning on the pro tour or has a sponsor backing her, one wonders what the Sirimallas will do to survive.

Every year, the pressure to commit comes earlier – and that at the expense of other career options. By now, most competing girls have left conventional schooling. Indeed, Sanjana studies only sporadically, her day being dominated by training of one form or another, geared towards tennis.

Up at 4:45 am, blanketed by predawn shadows, Sanjana makes her way to the tennis courts where she does two hours of fitness. After having breakfast and when the sun is up, she practises two hours before lunch. Nourished and napped by afternoon, there is yoga, another two hours of tennis and swimming – all before retiring to bed at 8:30 to do it all over again. “That’s my day”, says Sanjana, shrugging.

Renne’s routine is less intense but equally serious. She practises three hours a day and works out with a fitness coach for an hour. Unlike her RTW rival, Renne still hasn’t left school; her mother says she studies most evenings.

Averaging 18 tournaments a year since age eleven, Sanjana’s dedication to her sport is remarkable. Does she have any regrets? “Not at all,” she says. “To do anything great in life, you have to work hard and make sacrifices.”

And, she shows no signs of missing out on being a ‘normal’ teenager. “See, when I went to school and was around those girls who only wanted to go to the mall or spend hours on their mobiles, I would think, they are wasting their time. I want to make best use of my life. I don’t want to waste it,’ says Sanjana.

Being different or doing something outside of the norm can be isolating – but to Sanjana, her social life is full. “I celebrate with my sister whom I love the most, and also my parents after winning a tournament. And I can interact with others who share my passion for the sport all over the world. Tennis can do that for me, at least I hope,” Sanjana reflects.

Indeed, RTW, if nothing else, offers kids like Sanjana and Renne the chance to bond with others, irrespective of nationality or where borders are drawn, over their common love of sport. In an age when politicians talk of erecting walls, putting their people first, and going it alone, RTW offers the antidote: one in which private citizens and institutions engage on an individual or community basis without the need for political patronage.

For girls like Sanjana and Renne, RTW holds out both the hope of fulfilling their dreams and the promise of an extraordinary experience. Sport, after all, is about more than hitting a ball over a net; it’s about building character and a sense of community across language, culture and political boundary. And, whether or not victory comes or eludes, that is how champions in life are made.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine