BOOK REVIEW – ‘YOU THINK IT STRANGE’

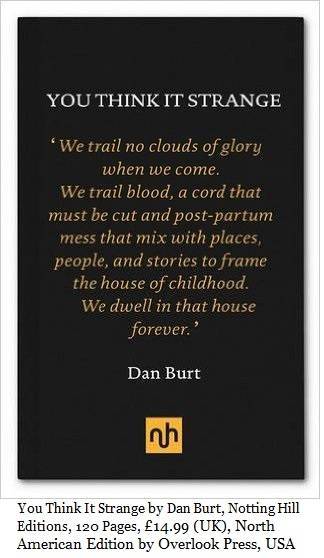

“We trail no paths of glory when we come. We tail blood, a cord that must be cut and post-partum mess that mix with places people, and stories to frame the house of childhood. We dwell in that house forever.” – Dan Burt, You Think It Strange

Book Review – You Think it Strange, by Dan Burt (Notting Hill Editions, UK 2013 with International Editions, forthcoming)

By S.B. Veda

Everyone and their mothers, these days, it seems, are writing memoirs. I pick up many and think, ‘why should I be interested in this person’s life? What’s so compelling that I should spend time and money to learn about it? But poet, Dan Burt’s memoir, You Think It Strange, is distinctive from these from cover to final word. Throughout, it never fails to engage and, by the end, one is left feeling an amalgam satiation and wanting (for more that is).

A single quotation appears on the front of the UK edition. And, that alone made me flip it open immediately: “We trail no paths of glory when we come. We tail blood, a cord that must be cut and post-partum mess that mix with places people, and stories to frame the house of childhood. We dwell in that house forever.”

Talk about a hook.

It should come as no surprise then, that Burt is an experienced fisherman in addition to being a butcher, lawyer, businessman, and writer; he knows well how to lure the reader in – and that too, brilliantly.

It should come as no surprise then, that Burt is an experienced fisherman in addition to being a butcher, lawyer, businessman, and writer; he knows well how to lure the reader in – and that too, brilliantly.

I first met Burt at a literary festival in Norwich, England. These are not typically places where one is apt to make friends or even strong connections. People collect cards, email addresses, and then tend to move on. But there was something in the powerful undertow of rage amidst the eloquence of his poetry that drew me into his world. I felt compelled upon arriving back in India to find out about the life that inspired the words, and ordered his memoir, straight away (it is still not available as a local book in the subcontinent; hopefully that will change, soon). That’s really what the book is meant to do – give some background and context for the poetry.

Still, the story stands tall on its own. Burt quickly launches into the violence of WW I anti-Semitic pogroms that forced his paternal grandfather to leave Russia for America. Then comes the casual brutality of his mother’s side, the Kevitches who were the ‘tough Jews’ of the Tenderloin area of Philadelphia. His father Joe was a butcher – and mother, Louise, the scion of a Jewish-Italian crime boss whose criminal enterprise ruled South Philly for some fifty years since The Great Depression.

He’d been reared in a neighburhood for which violence and criminality (from petty theft and extortion to murder) went hand-in-glove; despite some petty juvenile trouble with the law, Burt was repelled by the environment. The police offered little relief: His uncle Abe, an officer of the vice squad was the quintessential ‘bad cop’, embodying all the characteristics and proclivities of the criminals from whom he was to protect society. In the Tenderloin, the only line distinction between cop and criminal was the uniform.

Burt recalls Abe having regular arguments with Joe as he questioned what kind of life a butcher’s living was providing for his sister, especially when joining the Kevitch family ‘business’ could provide so much more. For all Joe’s anger, he refused to be drawn into a life of crime. (There would be compromises – a finger on the weigh scale and such – as was not uncommon in the neighbourhood – but on the whole, Joe made a legitimate living.) And, he made his son, Dan, learn the value of manual labor early on (perhaps to keep him out of trouble) putting him to work in the butcher shop at age 12.

Burt’s recollections of being made to work in Joe’s Meat Market are telling: Joe Burt kept a loaded .38 caliber revolver hung on a leather strap behind the cash register – it accompanied a black jack and baseball bat, all of which his father had to use on occasion.

Burt’s recollections of being made to work in Joe’s Meat Market are telling: Joe Burt kept a loaded .38 caliber revolver hung on a leather strap behind the cash register – it accompanied a black jack and baseball bat, all of which his father had to use on occasion.

The butcher shop depicted in the book is just the kind of pre-culinary hell that makes one think seriously about never putting a morsel of meat on one’s mouth: “You could hear rats – we called them freezer rats – scuttle away when you opened the door to the large walk-in freezer opposite the back room. They gnawed through a foot of concrete foundation and thee-inch plywood floor to nibble frozen turkeys stored for the holidays. We shaved off the chewed areas with the band-saw to remove the teeth marks before the turkeys went on sale. When we made sausage, you could smell the rancid grease from the green pork trimmings that comprised it, as well as the sage mixed with sodium nitrite to turn the trimmings pink again.”

Though an atheist, for Burt, his Jewish identity is written in blood. The why comes through with the weight of a sledge hammer in the narration of how his grandfather learned that his entire family had been murdered in Russia just for being Jewish.

Settled in America, the roots laid down by the Burts were gnarled and twisted. A legacy of rage flowed down the generations. His father took his anger out in the boxing ring and on his family. Burt’s recollections of Joe are, at once, intriguing and chilling: “His fists rose at the slightest provocation against all comers and sometimes against me…He beat me with a strap when I was small, for talking back, disobedience, breaking a lamp, staining the carpet, and with his fists when I was older, for intractability, hitting my brother.”

The neighbourhood provided little escape. Burt was called, ‘Shit-Ass,’ by Meyer, his mother’s cousin, who inherited the mantle of leadership of the Kevitch crime organization from Louise’s uncle Abe. Here he sets the scene of The Tenderloin: “Prostitution, gambling, fencing, contract murder, loan-sharking, political corruption and crime of every sort were the daily trade in Philadelphia’s Tenderloin, the oldest part of town. The Kevitch family ruled this stew for half a century, from prohibition to the rise of Atlantic City. My mother was a Kevitch.”

Children born into such circumstance, generally die not far from where they came into the world. And, as a struggling primary student, young Dan’s options seemed to consist of either following in his father’s footsteps as a butcher/some other ostensibly honest blue collar job or to be less hypocritical if not more ‘honest’, and work for the Kevitch crime family.

Burt elaborates: “Not all Jewish boys become doctors lawyers, violinists and Nobelists: some sons of immigrants from the Pale became criminals, often as part or in cahoots with Italian crime families. A recent history calls them “tough Jews”: men like Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Seigel, who organized and ran Murder Incorporated for (Charles) Lucky Luciano in the ‘Twenties and ‘Thirties and Arnold Rothstein, better known as Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby, who fixed the 1919 baseball World Series. The Kevitch family were tough Jews.”

After near failure early on at school, an IQ test, revealed that Dan had more to offer the world – if only he could tap into that latent potential. Absent any semblance of culture, art, and beauty, he grew up in an environment that did not inspire his intellect. So, he battled with his fists instead of his words. But, in time, this would change…

Lust impelled him to rise. Determined to impress a girl, Burt broke away from his peers and applied to Central High, a prestigious high school in Philadelphia. He got in but was suspended on the first day after his closed fist came crashing on the jaw of an insulting classmate during the opening assembly, sending him hurtling to the floor. Later, called to the Principal’s office, the pride Joe took in his son’s act of violence startled the school’s top administrator. It was not an auspicious start for the the knew student from a different background than most.

Burt proved to be a diamond in the rough: his exceptional qualities needed to be nurtured. Recognizing his, a faculty member took him under his wing. The troubled high school student was circumspect but his suspicions could not dim the light that broke into the dark room that was his upbringing. Elucidating it in typical elegance, Burt writes, “I was suspicious – no teacher had shown interest in me before. But if the temple veil was not rent…there was at least a small tear.”

Curiously, his refuge from the tumult of circumstance was the same as his father’s: the unending expanse of the sea. The two would embark on regular pilgrimages to the coast where The Tenderloin could not reach them. There, in the lap of Poseidon, the butcher and his son would sit and fish as the waves rocked their worries away. He has written about this the bond that developed over water in his poetry. In these sections, the book very much complements Burt’s poems.

Perhaps it was during one of those trips that Dan Burt became determined to, one day, live by the sea. He has been doing so for more than two decades in his home in Maine. His office at Cambridge also overlooks the water.

Events gain momentum as the boy grows into a man, (pages are apt to be turned quickly) speeding to a climax in which Burt’s personal life comes to a head with his professional ambitions, and a different path presents itself from author’s struggle to get out of Philadelphia. For a brief period as Dan describes being married and studying at the presigious, LaSalle College as a kind of safe harbor. We start to root for his simple life in Philadelphia with a new bride. But bone-crushing tragedy shakes both ends of his life, the personal and the professional. Death upon death, destruction preceding rebirth.

The tales told in You Think It Strange are nothing less than riveting, pages flipping by all too quickly as one doesn’t want this memoir to end.

Memoir writers can be tempted to reflect all too nostalgically – or else exaggerate both the highs and lows. Burt navigates through these polls with ease, never relenting to sentiment, and it all seems brutally real.

His prose is succinct and elegant, and facts are rendered true with a novelistic narrative flow.

The only drawback of the memoir (if it can be so termed) is that it may well end too early. We are left wondering about Cambridge, Yale, and beyond – Burt’s making his way to becoming a successful lawyer, businessman, Cambridge fellow and accomplished poet. We wonder about Joe’s death, and Dan’s estrangement from his brother. We wonder about love and loss. Lastly, we wonder what made him sail so far away from The Tenderloin that it required crossing an ocean and changing his citizenship.

Burt’s life is a gripping tale of the American dream, at times shocking and sad but not without humour and hope; I felt like I was reading a prequel to Fitzerald’s opus, The Great Gatsby (Gatsby in the making, only a legit version of the rise)- and this, fast-forwarded in time and narrated from within. Burt has treated us to a delight in Part 1 of his remarkable journey, and we are left ever in want of future installments.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine