Bharat on a Budget: A Bold Experiment From Two Self-Confessed Yuppies

By SB Veda

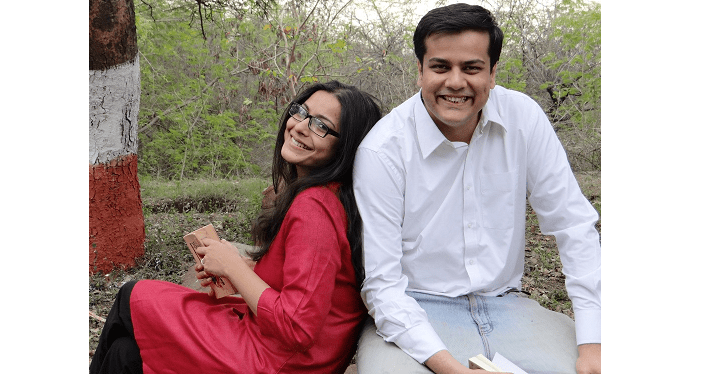

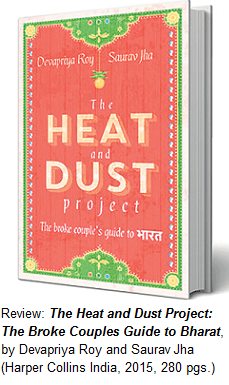

There are travels and then there are journeys and there are adventures – and then there are screwball adventures. Subscribers and viewers of The Global Calcuttan were treated to a comically narrated glimpse into the stuff of The Heat and Dust Project when we interviewed one of its authors in 2014, the delightful novelist, Devapriya Roy. The best-selling author of The Vague Woman’s Handbook> and The Weight Loss Club: The Curious Experiments of Nancy Housing Cooperative teamed up with husband Saurav Jha, an economic journalist and author in his own right, to embark upon a journey on the cheap throughout India – spending a barely believable average of Rs. 500 a night. With thin wallets, they narrate tales of curiosity, comical suffering and companionship that combine into an incomparable travelogue.

There are travels and then there are journeys and there are adventures – and then there are screwball adventures. Subscribers and viewers of The Global Calcuttan were treated to a comically narrated glimpse into the stuff of The Heat and Dust Project when we interviewed one of its authors in 2014, the delightful novelist, Devapriya Roy. The best-selling author of The Vague Woman’s Handbook> and The Weight Loss Club: The Curious Experiments of Nancy Housing Cooperative teamed up with husband Saurav Jha, an economic journalist and author in his own right, to embark upon a journey on the cheap throughout India – spending a barely believable average of Rs. 500 a night. With thin wallets, they narrate tales of curiosity, comical suffering and companionship that combine into an incomparable travelogue.

The two self-confessed yuppies hailing from Calcutta and based in Delhi, abandoned their nine-to-six lives in favour of pursuing a late gap year about which they ruminate in the first chapter, contextualizing their bold (my word) if not insane (their word) experiment. Well it is certainly harebrained, that two young, well-qualified consumptive members of the liberalization generation should chuck away all that they’ve seemingly been working for to tour India on a daily budget of what they might have previously spent on coffee and a meal at Barista or a mall.

And, that’s one reason to read this book – the sheer audacity of the idea in a country whose story is increasingly being written about by India Inc.. Money seems the goal of the young in India today. If nothing else, this book looks beyond the bank account, and informs us that there is a whole world out there open to discover. Why should young India then be chained to their desks?

So we are off with them – through Gurgaon to Jaipur, to Mayapur.. to Dharamsala.., and caught like they are between an irresistible force and an immovable object: freedom and a tight budget. This could easily be apt characterizations of the authors, respectively, Devapriya and Saurav. From the preview of their trip of finding a two star hotel with a bathroom stained by betel chew and tobacco in Jaipur to embarking on the trip by bus from Delhi, Devapriya is the free spirit while Saurav plays the practical spouse (something of a downer but a necessary component of this dynamic duo).

They argue (well, comically) over a list of things to bring, what kind of gear to use, where to start the journey. Devapriya’s aspirations and thinking are in the clouds, Saurav’s on the cold hard Earth. The book soon becomes as much about the dynamic of their relationship as the movement across highways and dirt roads.

After a ticket-seller at the counter for a Silverline bus informs them in characteristically paradoxical fashion that, “many small VIPs take this bus,’ they are soon disembarking Delhi through Gurgaon. Here, with Saurav apparently dozing, the novelistic quality of Devapriya’s prose flows full force: ‘Beyond Gurgaon, fields of mustard begin in bright yellow waves, often interrupted by ‘development’ as though it were a pompous character from an ancient play that has wandered into the current Indian vocabulary and remained,’

We see much of the trip through Devapriya’s eyes, and this is a real strength, allowing the tumble of her words to set a pace and tone. Saurav is her foil, and she goes to the well often for comic relief (but it doesn’t get old). He is ever the economist, bookish and almost bullying. But we like him for it.

Her lens is sharp and focused, giving us a vivid picture of what she sees. Her observations of people are as much in evidence as her putting us in a particular time and place. There is a particularly interesting account of a party in a Jaipur hotel, ironically called Veer (or brave) Rajput Palace, which comes to mind:

‘The occupants of these rooms have spilled onto the landing. They look up as we pass. It is a large party of yojng men in colourful shirts and white trousers, hair slicked back, chunky watches on wrists. They are milling about the corridor, sitting on the bed, chewing chicken legs, humming loudly in the next room and talking on cell-phones; they seem to multiply before my eyes. there is a girl in a crimson salwar-kameez, tinkling jewelry, golden butterfly clips in her hair, standing outside the first room and talking to one of th wither trousers earnestly. Another girl emerges from one of the other rooms, her hair tied in a topknot, her baby-pink salwar-kameez dotted with hundreds of glittery silver sequins. The interrupts the couple urgently, her high heels clip-clopping. I am transfixed.’

Throughout, quirky and interesting people, the kind to whom one wouldn’t be exposed in four, five or seven starred establishments. And with these accounts comes character, the stuff of life.

Just as Devapriya’s reflections are like storied, narrative, Saurav’s are more textbook-like and a little clunky to her ebb and flow. Of Delhi university days, he writes of intense bursts of anxiety ending brief spells of bliss followed by intense bursts of sightseeing; of embarking in Jaipur, he writes of ‘sallying forth’. He uses words like impecunious. Let me not belabor this review with more criticism of otherwise intelligently formulated prose; I shall be impecunious with it.

Pages to flip by at a nice pace, Devapriya’s prose populating more than Saurav’s, though Saurav’s account of his mother’s battle with cancer, is moving and serves to humanize him to the reader, which by the time the snippet is shared, is somewhat needed.

In addition to having a novelistic quality, the book can be drawn upon for some practical travel lessons. Cast against the history and folklore, which Saurav so effectively recounts, contextualizing the journey, the book does stand up to any other travel title. The Rs. 500 a day price tag is no mere gimmick. The book is about making the best of it in an environment of scarcity, crossing borders and breaking boundaries despite having a set ceiling.

If there is one irritant in the book, it is the editing. Perhaps in the rush to get it out, there were some slips: certain clear grammatical errors are present in some places. One doesn’t expect such poor editing in a publisher like Harper Collins. The publisher has put out a lot of non-fiction books, this year. One wonders if they spread themselves too thin.

An aspect of the book that seems its own character (much as it appears in Devapriya’s last novel) is food. From street tea and samosa stalls to Italian fare, ‘swimming in cheeses sauce,’ as Saurav describes it, to dhabas, Bengali restaurants and home-cooked food, the culinary alone makes one want to catch a train, take bus, or simply head outside. And, this is a central part of travel, experiencing not only sights and sounds but smells and tastes, literally taking in the experience.

My maternal uncle proudly said he never travelled, for it was a luxury he could not afford. Devapriya and Sarauv demonstrate that journeys are not only for those with means, they are also for those without – but not for the faint of heart. That said, with book in hand one doesn’t require the courage of the authors: one simply needs to turn a page to turn on the experience The Heat and Dust Project. They are tales not likely to be forgotten, either at home or on the road.

The couple is currently working on a sequel called, Man Woman Road, which continues the journey that is to ultimately form a trilogy. In the process, they will surely etch themselves memorably into the psyche of many a traveler.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine