Calcutta Wetlands: Are We Walking in Chennai’s Footsteps?

“In cities like Chennai and Kolkata, marshes and flood plains play a very important role in draining out overflowing rivers. This doesn’t seem to have been understood by urban planners. One can’t encroach the buffer around rivers without consequences.”

By SB Veda

CALCUTTA – If Wordsworth’s words ring true and a lake can carry you into recesses of feeling otherwise impenetrable, it follows that with the penetration of concrete into earth comes increasing vulnerability. Ask an ecologist and s/he’ll say that the process is a slow death, coming to notice periodically as cataclysms manifest. This, of course, was alarmingly evidenced in Chennai, last November. Given the similarities between that city and Calcutta, it seems reasonable to ask: are we walking in Chennai’s footsteps?

Unfortunately, concerns about the environment tend to be dismissed out of hand by most public officials in Calcutta – too many other other priorities…jobs, development, etc. Even the reaction down south was hardly encouraging: Tamil Nadu’s controversial Chief Minister, Jayalalithaa first showed indifference, saying heavy rains were common and routinely caused damage. Later, she claimed credit for persuading Prime Minister Modi to declare the floods a national disaster and allocate relief funding.

Elsewhere, complaints abounded that such disbursements weren’t being equitably distributed among incident-stricken states. (Flooding, you see, is not terribly uncommon in the East, though nothing like Chennai, 2015 recently comes to mind.) And so, an absurd Chennai-envy gained traction in certain corridors of Bengal where elections are upcoming in 2016. But as politicians at both the state and central level continued to utilize events to maximum advantage through the New Year, none seemed terribly interested in addressing the root causes. It was and continues to be an inconvenient truth that these events aren’t simply a function of heavy rain and high tide. A disaster like this had been in the making for decades due to the depletion of waterbodies and degradation of wetlands.

CHENNAI AND HER IMPERILED WETLANDS

Historically, Chennai has been blessed with a healthy number of waterbodies over an expansive area. Proximity to the coast made it the gateway to the South. In fact, the British East India Company made Madras (now Chennai) its base before moving up the Bay of Bengal. While not currently known for agriculture, the land was fertile and surrounding villages in Tamil Nadu cultivated produce that more than supplied local needs. This, combined with presence of robust fish stocks provided ample food.

Chennai underwent a steady process of industrialization from the time of the British. Its location as a strategic port made it a convenient hub of manufacturing. And, the Tamil people proved capable, reliable, and productive workers as well as managers. Chennai is often mistakenly lauded as a growth success story due mainly to the impressive pace of change. It is one of the fastest growing cities in the world, and now competes with Bengaluru (Bangalore) and Hyderabad as IT centre, outsourcing hub and processing point for financial services. But this has spurred construction at a frenetic pace, unplanned, mindless even – and, in many cases, illegal.

Around Twenty years ago, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras pegged the number of wetlands in and around the city to be at around 650. Less than 5% (27 to be precise) exist, today. And, the total area taken up by major lakes, according to the state Water Resources Department, has more than halved during roughly the same period. Two decades of cement-impregnated development has sucked the earth dry at dramatic pace. The wetlands surrounding Chennai – complex ecosystems saturated with water – acted as natural flood barrier. Their total area has decreased by a factor of ten.

It is a country-wide problem: one-third of India’s wetlands are already wiped out or severely degraded because of habitat destruction, pollution, and encroachment. In low-lying coastal areas where heavy rains are common and high tides can occur, the consequences are potentially disastrous.

So, why is this relevant to Calcutta? Well, the two cities have many similarities: both are low-lying and near sea-level. In fact, Calcutta’s average elevation is five feet lower than that of Chennai, potentially putting the population at greater risk. Both cities are located off the Bay of Bengal, and are home to major rivers. The importance of Wetlands to the ecological life of both is critical – and both have suffered and continue to suffer from illegal encroachment.

While Calcutta isn’t growing nearly at the rate of Chennai and business is far from booming, speculative real estate has been ballooning over the past five years as property has become (as gold once was) a place in which to invest black money. The cash is both locally sourced and flows in from neigbhouring states. Significantly, too: heavy rains occur regularly in both places, so minor flooding is periodic, and water-logging is incessant during monsoons.

THE NATURAL MIRACLE OF THE CALCUTTA WETLANDS

In 2002, the wetlands east of Calcutta (The East Kolkata Wetlands or EKW as they are now known) were deemed an area of international ecological importance, and have since been protected by the United Nations Ramsar convention. Four years later the state government passed a law regulating the management of the area. At 12,500 Hectares, the size of the site is significant. No less than an order of the High Court at Calcutta can sanction conversion of the protected land for other use. But this hasn’t dissuaded land sharks from building illegally and continuing their encroachment.

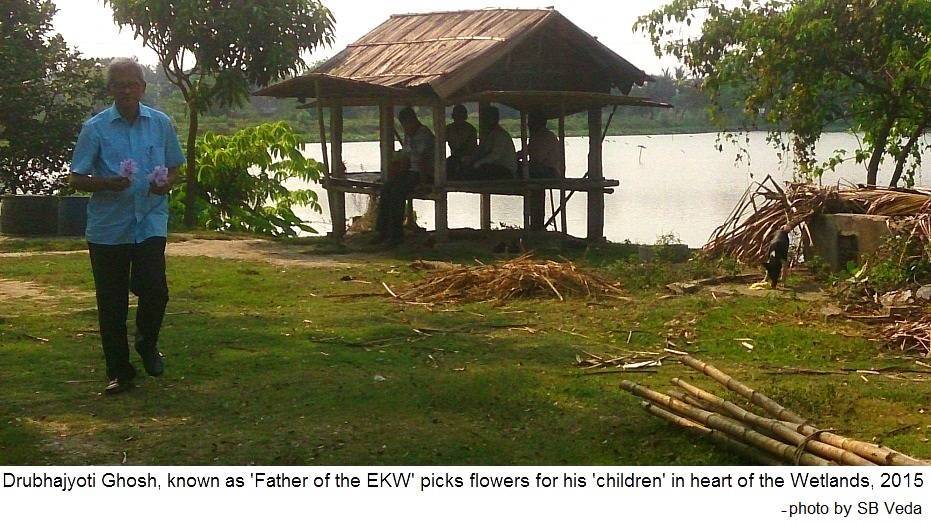

Dhrubhyajoti Ghosh, the engineer turned ecologist who coined the term East Calcutta Wetlands (later East Kolkata Wetlands) and is also credited with achieving Ramsar status for the EKW, remains concerned about its future and that of Calcutta. “It is only a matter of time if present trends endure,” he says of the probability of further environmental decline. “It is getting hotter, year-over-year, and there has been flooding. This is likely to continue though it’s simplistic to say we will have a situation like Chennai; the drainage system is totally different. Calcutta is much better off than Chennai in that respect. Still, we should take it as a sign of things to come and take corrective action.”

As beneficial as wetlands are for cities like Chennai, the EKW is an even more vital organ to the survival of Calcutta. “They are not just floodplains,” says Ghosh. “They serve a more complex and significant purpose. They are really the kidneys of the city. Calcutta has no water purification system in place other than EKW.”

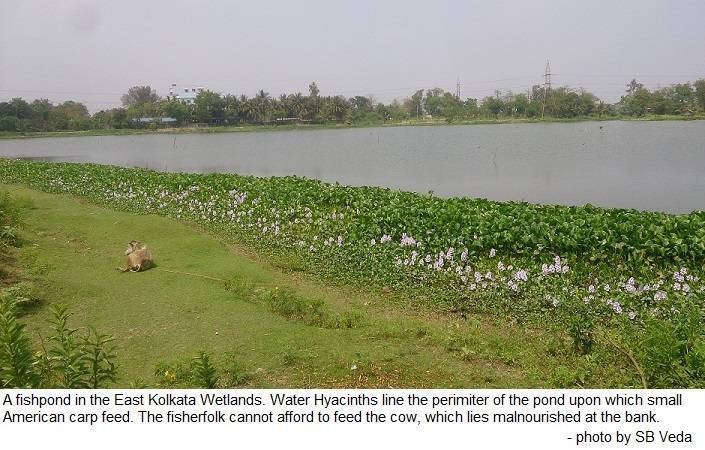

What makes the EKW unique is a combination of factors: its sheer size; the number and complexity of channels and ponds; and the topography of the land, which tilts from West to East. Water flows downhill from Calcutta through a multitude of narrow canals into a series of marshes and ponds. The raw sewage becomes filtered as its flow is controlled and released from one natural repository to another. Sunlight kills the bacteria in the water, sanitizing it for other uses. It is a natural waste-water treatment plant like no other in India, perhaps even the world.

Plankton growing on the surface of nutrient-rich ponds sustains a robust aquaculture, which, in turn, feeds the city. The ecosystem is intricate and fragile. The drained waste water from Calcutta flows into the fish ponds – but not directly. On the way, ultra-violet radiation (UV Rays) from intense sunlight acts to decontaminate the sewage (interestingly many Calcuttans pay for UV treatment of their tap water to make it potable). The Sun’s ray’s provide heat and light that trigger biochemical reactions. These kill the Faecal coliform bacteria in the sewage (the germs that cause foul odour and severe illness). The water is cleaned of this bacteria so completely that even mechanical sewage treatment plants in India are unable to replicate it.

It is this nutritive water that flows into fishponds, serving as ripe feed for plankton and algae on which the fish subsist. Smaller ponds are around two to five hectares in size. The larger ones are ten times that. Fish are farmed in a series of pools, a maximum of around five to six feet deep called Bheris beginning with the nursery pond. After reaching a certain size, they are raised in a rearing pond and finally cultivated as catch in a stocking pond. The rearing ponds are manually aerated by the fisherman who use wooden planks and bats to literally beat the oxygen into the water. Each needs a proper inlet-outlet management system but due to the natural water pressure created by force of gravity, pumps are seldom necessary. The main requirement for a productive fish pond is the proper supply and quality of waste water, which arrives minute-by-minute from the many sinks and toilets of the city.

The effluent from the fishponds is then made to drain further southeast where paddy fields have been strategically placed to benefit from the flow. And, the rest of the water is used to irrigate farms that are fertilized by garbage, which is dumped in a landfill located in a part of the area called Dhapa. Waste has been dumped here from the mid-1800s. Since it was largely biodegradable, the fertility of the soil improved dramatically and people started to farm the land. These ‘garbage farms’ supply around 40-50% of the city’s produce markets. The costs and carbon footprint of stocks at local markets are thereby kept perennially low.

WHY MERE RECOGNITION IS INSUFFICIENT

All over India, Wetlands replenish groundwater, mitigate flooding, recycle nutrients, purify water, and provide economic livelihood for inhabitants and nearby urban populations. They serve as habitat to an array of species of flora and fauna unseen in metropolitan zones, and yet many (like the EKW) are located in close proximity to cities. In May 2011, the Indian government compiled a national inventory atlas and a status report on wetlands. The report classifies as wetlands a total of 10 million hectares, excluding rivers, paddies and man-made waterbodies. Of this, only 145,000 hectares (or 1.45% of the total classified wetlands) is currently protected under the Ramsar Convention.

State governments are not motivated to get Ramsar recognition for wetlands because of so called development needs (i.e., they want to fill in the waterbodies and build on the land). Also, the Ramsar Convention is merely voluntary, so the UN has little role to ensure that recognized sites stay protected. “It has no teeth,” says Ghosh. “And, unmotivated officials have much wiggle-room. Even in Calcutta, we managed to get the application through almost by hoodwinking the concerned Minister.” Since then, the government has been dragging its heals much less been proactive.

Faced with repeated delays and pushback in 2001, Ghosh, the Chief Environmental Officer of the state at the time, had the Ramsar application placed strategically in a pile that the Minister’s secretary hinted would be signed without much attention being paid. The application sailed through – and afterwards, Ghosh suffered retaliation. His pension was held up for years after retirement.

“Desperate times call for desperate measures,’ he says. ‘But time has passed, and we conservationalists are still desperate.”

The World Bank has gone further, having issued a report last fall called ‘Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia’ that identified Calcutta as being among the top cities due for a 100 year flood (the kind of severe flood that occurs once a century). With mother nature firing a warning shot in Chennai, the continuing indifference is truly remarkable.

Sugata Hazra, director of the School of Oceanography Studies, Jadavpur University agrees: “If heavy rainfall is coupled with high tide, Kolkata has a chance of getting flooded easily,” he said speaking to The Hindu, last year.

CHILIKA LAKE – A WETLAND SAVED

The situation is hardly irreparable as the state of Odisha has shown. A once devastated wetland area, Odisha’s Chilika Lake sprung back to life after concerted and determined conservation efforts. It is the second largest salt water lagoon in the world and the largest winter habitat for migratory birds in the Indian sub-continent. Chilika also supports around 200,000 fishermen who are dependent on the lake for their livelihood. And, significantly, it is one of the last bastions of the endangered Irrawady dolphins.

The area was the first in India to be recognized by the UN Ramsar convention in 1981. Later it was put under the Montreax Record due to concern that a change in its ecological character was imminent.

Recognizing that the situation was on the verge of becoming irreversible, and concerned about the significant numbers of people who were dependent upon the lake’s resources, the Government of Orissa as the state was then known, set up the Chilika Development Authority (CDA) in 1992. The CDA was registered under the Indian Societies Registration Act and established as a quasi-governmental body under the administrative jurisdiction of the Forest and Environment Department. Its charter included: protection of the Lake ecosystem and genetic diversity; formulation of a management plan for Integrated Resource Management and wise use of the lake’s resources by the community; and collaboration with international institutions for development of the lake.

The Chief Minister was put in charge of the governing body, which included elected representatives as well as experts and affected stakeholders such as scientists, community leaders and fisherfolk.

The Indian government committed Rs 570 million (US$12.7 million at the time) for implementation of the revitalization plan, and the monitoring was supported under auspices of the World Bank. In all, 7 state government organizations, 33 NGOs, 3 national government ministries, 6 other organizations, 11 international organizations, 13 research institutions and 55 different categories of community groups became involved in the project. And, the state sought the help of the Japanese government for technical advice and support.

The project successfully opened a new sea mouth to allow constant inflow of seawater to preserve the lake’s alkaline character. Sustainable monitoring of the lake increased the fish population and migratory birds started returning in large numbers. Today, Chilika Lake is one of the few thriving wetland ecosystems in India, and it remains and exemplary conservation story.

The project successfully opened a new sea mouth to allow constant inflow of seawater to preserve the lake’s alkaline character. Sustainable monitoring of the lake increased the fish population and migratory birds started returning in large numbers. Today, Chilika Lake is one of the few thriving wetland ecosystems in India, and it remains and exemplary conservation story.

A SHADOWY NEXUS OF POLITICIANS, BUILDERS AND GOONS

Unfortunately, the the imperilment of the EKW appears not to be a result of apathy, ignorance or bureaucratic bungling. Rather, it may well be deliberate, as one retired civil servant who requested anonymity told us, last year:

“In Odisha, so many people were dependent on the (Chilika) lake that the state government became invested in solving the problem. There was political will to do something. In West Bengal, the politicians are complicit with Real Estate companies. They are clearly on the take and any opposition is marginalized, intimidated or even physically harmed. The nexus combines to form nothing less than a mafia. They (developers) are being told, “Arey Don’t worry – go ahead and build. In due course all will be sanctioned” So, tell me, who else can so brazenly break the laws other than those who make the laws?”

Indeed, Ramsar Bureau representative, Lew Young expressed concern over the future of the wetlands, last year, following the pledge by West Bengal Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee to legitimize some 25,000 illegal constructions within the Ramsar area. Although no legal mechanism exists to do so (short of changing the law) the CM promised that ‘owners’ would ultimately be eligible to seek mutation from the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC). Mayor Sovan Chatterjee, went further, deriding conservationalists as elitist, stating that conservation of the Wetlands, “means little to the common man.”

But what of the fisherfolk, the farmers? These common men – men like Ram Mandal – are worried. A second generation fisherman at a cooperative fish farm, he feels threatened on many fronts. “We are a cooperative but cannot go to local banks for loans because the managers are Chamchas (in the pockets) of the real estate companies. We have to go all the way to NSC Bose Road (some 90 minutes by bus) to get loans and insurance because we don’t even trust the local branch managers to deposit our money!”

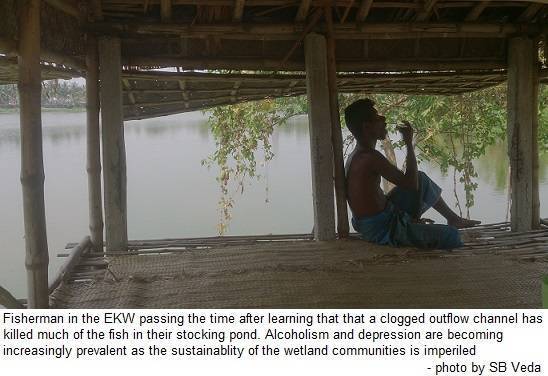

People like Mandal say they have no recourse. “Who will we go to… the police? Councilors? They are all part of it. Men from the KMC come with machines into our canals, and say they are dredging to clear water-logging in the city. And, then we notice that our water level is lower than before. Sometimes we find our inlet canals coming to a trickle or our outflow canals blocked. They want our ponds to dry out, so they can get taken over by promoters. Our children are looking for work in the city because we are no match for these powerful elements. The Netas and dadas (politicians and local leaders) are not for the common man. They are only for their wallets.”

Mandal’s story is not unique. Last February, The Times of India reported that in violation of court order and wetlands protection act, nearly 17 acres of the EKW near Chowbaga Mouza was being developed for real estate. The article alleged that builders had erected a wall around the plot within which they were depleting a vital stretch of Bidyadhari River – one of the most significant outflow channels of the city. “If it gets choked,” wrote Times reporter, Krishnendu Bandyopadhyay, “Calcutta will surely be flooded”.

The same article quoted an unnamed resident who described activities eerily similar to Mandal: “In the middle of the night on February 10, they (developers) brought JCB cranes to level the swamp, destroying its natural gradient.”

A contempt suit filed by another resident, Shankari Mandal in the High Court alleges that real estate developers block the water inlet channels, making the canal look like a regular field and not a water body.

“It’s easy to blame the builders and the politicians – but where are the voices of our citizenry in this? What about all the great Bengali intellectuals living here or abroad? Why aren’t they speaking up?”

Last year, Ram Mandal’s cooperative had lost stocks of fish worth 200,000 of rupees (a small fortune to the coop) due to a blocked outflow canal that caused their stocking pond to become toxic. “I won’t tell you what we found. Maybe I am talking too much on this – but it is clear that this was no accident. Those who did it took no step to hide their misdeed. It was to send us a message: As a cooperative, we are a threat because they can’t simply buy the owner off. They don’t want similar cooperatives to form because shared ownership gives fishermen some control. So, the answer is destruction.”

Indeed, studies (such as the 1994 Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture study of Belize fishing coops) have shown that collective ownership rights established pensions, educational funds, health benefits, and other initiatives that contribute to sustainable livelihoods. The coop system also helped improve industry standards and benefited consumers. It is this sustainability that the builders fear most in the EKW. The entrenchment of sustained aquaculture and farming is much more difficult to bulldoze than flora, fauna and stray human beings.

In 2014, Avijit Bakshi and A.K. Panigrahi studied socio-economic factors of several fisher-communities in West Bengal. Their work was published by Kalyani University. Among other findings, they recorded that roughly two thirds of fishermen consumed alcohol regularly and every single adult male smoked some form of tobacco (sometimes mixed with Cannabis).

They also observed that chewing of the betel nut was widespread even among the womenfolk. The results were surprising as the sociologists had expected some measure of under-reporting due to the conservative nature of Indian society (alcoholism in particular is looked down upon). Under the circumstances, the findings were alarming and indicative of a looming mental health crisis among members of these communities.

A DARK OUTLOOK

Months before the Chennai disaster, TN Ramachandra and his colleagues at the Centre for Ecological Sciences in the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, studied construction in Chennai for a paper to be published in the Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing. Using a combination of satellite imagery, which was then superimposed over topological maps of the Survey of India as well as from the Chennai municipality, his team found that since 1991, the city’s concrete structures have increased nearly 13 times while flood plains and open areas have been reduced by a fourth.

Ramachandra refers to Chennai in the same breath as Calcutta: “In cities like Chennai and Kolkata, marshes and flood plains play a very important role in draining out overflowing rivers. This doesn’t seem to have been understood by urban planners. One can’t encroach the buffer around rivers without consequences.” The consequences soon became apparent in Chennai.

Since then, for ecologists like Ghosh, frustration continues: “I said earlier that conservationalists are desperate. Unfortunately, Calcuttans are not so desperate. They are unconcerned. It’s easy to blame the builders and the politicians – but where are the voices of our citizenry in this? What about all the great Bengali intellectuals living here or abroad? Why aren’t they speaking up? Whatever their reasons, they are unconcerned with the environment. If it is not a priority for them or for the wider public, why should the politicians stick their neck out?”

Some have suggested that only severe climactic consequences such as what took place in Chennai can motivate the public. And, faced with disaster, politicians will be compelled to make changes.

Ram Mandal is more pessimistic. “It won’t matter,” he says. “Life is cheap in India. That’s why outsourcing is so successful. When the city is under water, the Netas will hire workers willing to act as human stilts for a few rupees. In the end, it will seem like they’re walking on water. It will be the rest of us who will drown.”

(The names of residents have been changed to protect their identities.)

In January, 2016, SB Veda led a group of writers and academics from the UK on a tour of the EKW by a Wetlands NGO called SCOPE.The delegation included Patrick Barkham, author and staff writer of The Guardian newspaper and Professor Vesna Goldsworthy, author and Co-director the University of East Anglia’s acclaimed Creative Writing program. The tour was part of the programme of an international literary project on place and writing.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine