Beyond The Raj: India Honours Fallen from WWI

Honoring Its WWI Dead, India Moves On From Its Colonial Past

Displayed with permission from Newsweek

It has taken a century for Britain and India to commemorate more than 70,000 Indian troops who died fighting in World War One, and it has taken India over 60 years to decide fully to mark the fallen in that and later wars.

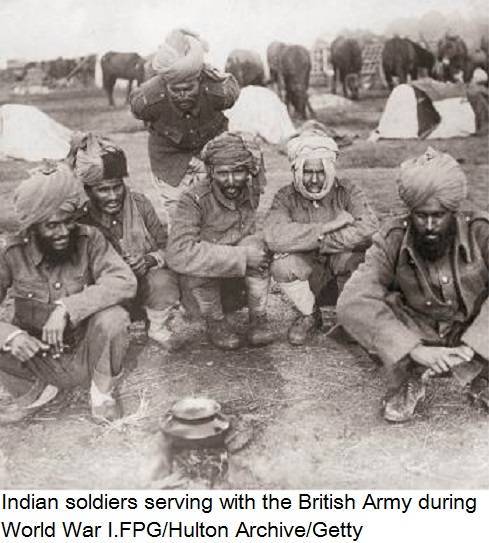

Over 1.4 million Indian volunteers served in Europe, Africa and elsewhere between 1914 and 1918 in what has become known as “India’s Forgotten War”. They were scarcely mentioned by either side during the 50t hanniversary in 1964.

India has now moved on from the post-colonial period that made it difficult for it to honor the troops who had been fighting with a variety of motives for an imperial power that after the war did not respond with rapid moves towards independence. The new Bharatiya Janata Party government is also nationalistically conscious enough to want to honor Indians who fought in wars before, as well as after, independence – and probably finds it easier to do that than past Congress governments. Till now, to commemorate the dead there has only been the India Gate memorial in Delhi, erected by the British in 1931.

The common view that now unites the former colony and its old colonial ruler emerged unpredictably at an evening event held at the Delhi residence of Sir James Bevan, the British High Commissioner, on October 30. Arun Jaitley, India’s finance minister (who till this weekend’s government reshuffle has also been the temporary but very active defense minister since the general election), paid a tribute to those who had fought in the war. He announced that a war museum covering all India’s battles would be built, in addition to a war history in printed, digital and film form that he had talked about before.

The visiting UK Defence Secretary Minister, Michael Fallon, honored those who lost their lives, and unveiled memorials to six Indians who won Britain’s highest military honor, the Victoria Cross. India’s chief of army staff attended the reception along other senior officers and representatives of families whose successive generations had served in the Indian forces.

When the event was first planned, it was not clear whether any senior Indian representative would bother to attend what might have been seen as an essentially British occasion. The top-level turnout was therefore significant in terms of recognizing the history, because the UK is not one of the current government’s top priority countries.

When the event was first planned, it was not clear whether any senior Indian representative would bother to attend what might have been seen as an essentially British occasion. The top-level turnout was therefore significant in terms of recognizing the history, because the UK is not one of the current government’s top priority countries.

The commemorations continued with a BBC World Service radio discussion, (recorded in Delhi a week ago) on the motives and impact of the volunteer force, and with traditional Remembrance Sunday ceremonies in Delhi and Mumbai.

Various books have been published to bring alive a part of India’s history that has largely been ignored. One of them is by Vedica Kant, an academic who has studied the Ottoman empire and has written If I die here, who will remember me – India and the First World War, which is illustrated with original photographs and documents. Another book, by Captain Amarinder Singh, a prominent Congress politician from the Punjab, comes with the eye of a former army officer – Honour and Fidelity, India’s Military Contribution to the Great War 1914-18.

It seems strange, looking back, that 1.4 million men should volunteer to fight in a war far from home that had absolutely no immediate impact on their country and that politicians who were then beginning to campaign for independence should not have objected to the contribution of the people and of the costs that were fully covered by India.

Few of the soldiers would have ever travelled abroad before. When they arrived for battle, they had insufficient clothing for the cold climate and were given weapons they had never used before. They were certainly not “a patriotic army”, said one of the experts on the BBC program.

Their contributions were controversially summed up in the broadcast by Shashi Tharoor, an author and former senior UN official who is now a Congress Party politician.

Putting the cost to India at £30 billion in current prices, he said, “It was Indian jawans [soldiers] who stopped the German advance at Ypres in the autumn of 1914, soon after the war broke out, while the British were still recruiting and training their own forces. Hundreds were killed in a gallant but futile engagement at Neuve Chappelle. More than a thousand of them died at Gallipoli, thanks to [Winston] Churchill’s folly. Nearly 700,000 Indian sepoys [soldiers] fought in Mesopotamia against the Ottoman Empire, Germany’s ally, many of them Indian Muslims taking up arms against their co-religionists in defense of the British Empire.”

The motives varied and included, as Vedica Kant points out, the chance to earn good money – a reason that has often led them to be dismissed unfairly in India as mere mercenaries. Kant reckons their earnings were the equivalent today of a respectable Rs25,800 a month (about $470). Some had loyalty to the King Emperor (though not as many as, it seemed, as the BBC program presenter would have liked) and a very few maybe to King and country. For most, however, it would have been the natural loyalty and bonding of a soldier with his regiment, plus the pride of going off to war and the respect that would be earned at home – though there were desertions and mutinies.

The politicians and independence leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi, who supported the war effort, did so in the belief that Britain would in return honor a commitment to hasten moves towards some form of autonomy or at least the sort of dominion status enjoyed by Australia and Canada. That however did not happen, which sharpened the subsequent demands and agitation for independence.

With such a history, one might wonder whether the fresh awareness of India’s sacrifice might now lead to the World War One being listed among the horrors of British rule, such as the Amritsar Massacre of 1919 where 1,500 peaceful demonstrators for the independence that Britain had denied India were killed on the orders of a British general. But it seems not, because India has indeed moved on.

John Elliott’s Implosion: India’s Tryst With Reality is published by HarperCollins, India. He can be read at ridingtheelephant.wordpress.com.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine