Bolly Tragedy Spotlights Desi Male Depression

SB Veda

“Indian boys are taught not only that ‘boys don’t cry’ but also if you pick at a scab – in this case a mental wound – it will never heal. So the message they get is, ‘just get on with it.'”

He was emblematic of young Bollywood, blazing a splendiferous trail through the Mumbai sky: young, talented, and bankable, Sushant Singh Rajput seemed to be bouncing to the beat of a signature item number. From TV to Bollywood films – coupling commercial triumph with critical acclaim – the thirty-four-year-old heartthrob was apparently living a dream. That the reality was a nightmare was tragically exposed when his lifeless body was found on June 14th, swinging from a rope tied to a ceiling fan in his apartment.

The cause of death: asphyxiation due to hanging.

The shocking news made headlines both in South Asia and elsewhere. In his native India, the press, Bollywood film community, and his large fan base struggled to make sense of the tragedy, for the young star had left no note. And, while his father had told police that he was aware his son had felt “low” at times, he had not observed any signs of depression in his boy.

Police uncovered a very different story: prescriptions for various medications and packets of anti-depressants were strewn across his bedroom; he had silently been suffering from a deep mental decline for at least half-year. It is alleged that he’d lost seven film deals over this time frame due antagonism from the Bollywood establishment, some of whom had mocked his modest upbringing and history of acting in TV.

His personal life, too, was balancing on a razor’a edge. Though he had mentioned to family and friends, his intention to marry his girlfriend, actress Rhea Chakravarti, there are reports that the relationship was rocky – and the two may have even split prior to his death. The actress admitted to police that she was staying with Rajput at his flat during the Covid-19 lockdown but had left following a heated argument. Her number was the last call Rajput made from his cellphone. It went unanswered.

While Rajput’s story has garnered much press and social media attention, the recent public dialogue belies a dirty secret that mental health issues and the inability to address them, have plagued South Asian men in recent years.

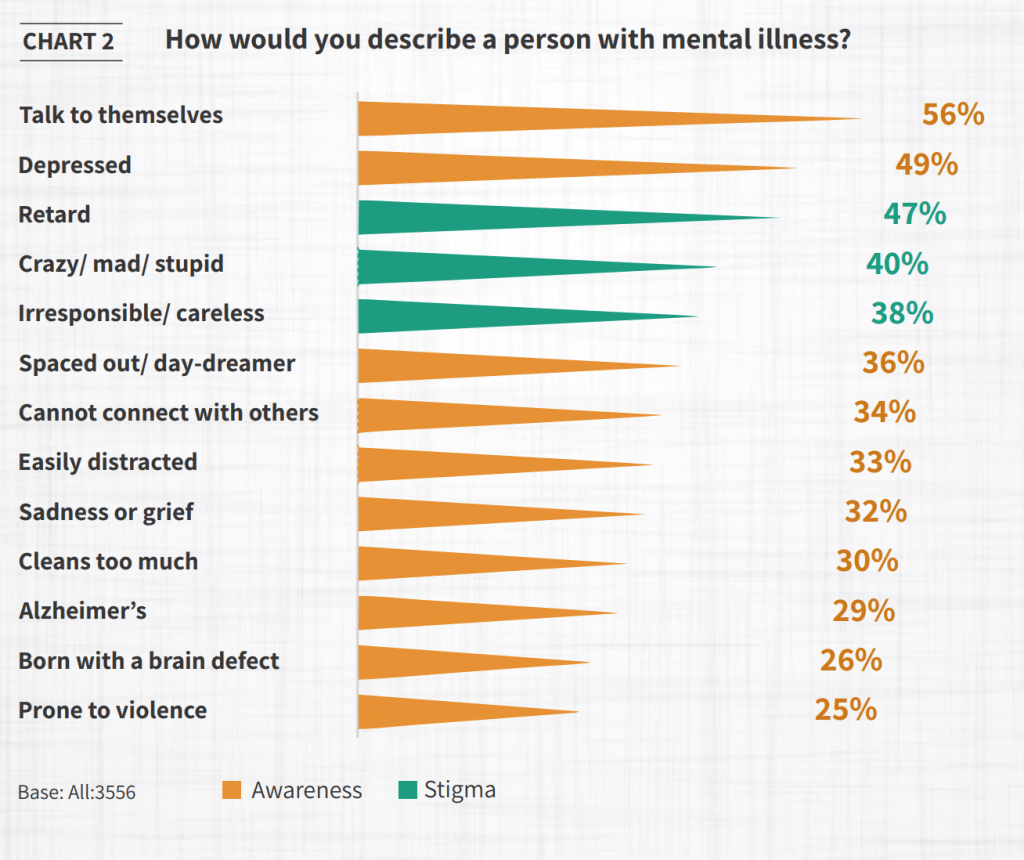

Notably, outside of India, the issue was studied in 2010 by Time to Change, a British national campaign aimed at ending stigma and discrimination surrounding mental health.

It found that South Asians with mental health issues had very different experiences compared to members of other communities.

The report said mental health was rarely discussed because of the risk it posed to a family’s reputation and status. Men in particular were expected to just ‘move on with things,’ rather than dwell on their pain.

Dr. Sanjay Sen, former head of the psychiatry department at a prominent Indian hospital (now practicing in the UK) concurs: “Boys and men are told not only not to cry – but also that if they focus too much on their mental anguish, just like at a scab, the wounds will never heal.”

He also says that South Asians have a greater sense of shame than other communities, and a culture of self-blame exists that borders on religious masochism.

“Many are taught that their pain is as a result of sins committed in past lives, and that the afflicted are thereby destined to suffer,” says Sen. This spiritual self-flagellation serves as a barrier to get help.

Machismo, too, figures prominently in the upbringing of the majority of South Asian males. With depression being equated to weakness by their rearing and social environment, South Asian men are often compelled to suffer in silence.

While wives can offer comfort to ailing spouses, it is not uncommon for a South Asian wife, having been brought up in a household in which the father figure never vocalized mental anguish, to similarly view low mood in a husband as weakness.

“A wife is often conditioned to rely on her husband for strength,” says Neelam Munshi, a clinical psychologist in private practice in Kolkata. “And, not the other way around.”

“Indeed, Indian women often have to contend with overbearing in-laws, the pressures of child-rearing and tending to the home – as well as, these days, doing a job. It’s a lot to handle. The idea that they should have to play nursemaid to their crying husband, under such conditions, can actually be quite repulsive to them,” Munshi adds.

“At the same time, these women will dote over their male children, encourage them to cry on their shoulders – even offer their breast as comfort well after the normal breastfeeding period is over.”

For families, says Munshi, this is a double-edged sword: “Ironically, the conditioning that promotes the notion of the strong husband as desirable, sometimes prevents battered women, too, from seeking help.”

By consequence, married South Asian men, especially immigrants and those in arranged marriages, have nobody with whom they can give voice to their suffering. Without an outlet to vocalize their angst, many turn to maladaptive coping mechanisms that, while providing temporary relief, end up doing more harm.

As a result, alcoholism rates and drug use are rising among South Asian men both in South Asia and in the adoptive countries of South Asian immigrants.

Traditional means of treating substance abuse such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) are not culturally attuned or flexible enough to integrate South Asians into the fold. Cultural impediments make it difficult for many South Asians to accept such dogmatic approaches to treatment, which have also been described as Christian-based quasi-religion meant to compete with the belief systems ingrained in non-Christian South Asians.

Changing family patterns coinciding with modernity have added to the isolation of South Asian males. Historically, when South Asians lived in joint-families (those in which adult siblings and their families live under one roof) South Asian men could commiserate with brothers, cousins – even go back to the childhood defence mechanism of taking comfort from their mothers. With nuclear families being the norm even in South Asia as well as abroad, family ties no longer offer support system that aided troubled men.

While mental health resources are available particularly in the Western countries where many South Asians have settled, getting men to avail of public and private therapeutic resources has proven to be an added challenge. Poonam Tukvar and Srividya Iyer of McGill University and David J. Hansen of the University of Illinois, jointly studied the approach of the South Asian diaspora community to psychological treatment and concluded that, “Seeking help from external or mainstream resources is considered shameful and loathsome….seeking professional help outside of the extended family, most individuals do not present to physicians and clinicians until their symptoms are severe.” Some do not present at all before it’s too late.

Indeed, for many in the American South Asian community, the horrific 2019 murder-suicide of IT professional Chandrashekar Sunkara and family is a case in point and remains an open wound. Sunkara, a US Citizen, and resident of West Des Moines, Iowa, was able to legally purchase a gun fifteen days before fatally shooting his wife, Lavanya and two children, and then turning the gun on himself.

A family friend from the Telugu Association of North America who wished to remain anonymous told the Times of India that Chandra had been severely depressed and there may have been a family dispute troubling him. Had Sunkara sought help, the tragedy might have been avoided.

The friend also lamented the fact that Sunkara did not seek treatment: “Chandu (Sunkara) could have consulted a psychiatrist in case of acute depression; the family should have intervened in case if they knew about his psychological condition,” the friend said.

Public awareness is slowly lifting the cone of silence. And, Rajput is hardly the first South Asian origin celebrity to face mental health challenges. UK cricket star, Monty Panesar has publicly battled mental health issues, openly calling out the culture of shame and self-blame that is endemic in the South Asian community.

Panesar, who has suffered from paranoia and anxiety, is one of the few celebrities of South Asian origin outside of the region to openly speak out about his problems.

Speaking to the BBC, Panesar, who is now a mental health ambassador for the Professional Cricketers’ Association, said the sport was understanding of his circumstances.

That said, he had a very different appraisal of the South Asian Community.

“In our Asian community there was no understanding of what mental heath is…A lot of young Asians came forward [after I went public] and said, ‘we’re glad you opened up because it’s a huge taboo in our community’,” Panesar told the BBC.

Acceptance of the use of anti-depressants and medications used to control alcoholism and drug abuse has become more widespread, and so South Asian men are opening up to their doctors much more than in the past. But talking about problems to a therapist is still frowned upon.

As tragic as Rajput’s demise was, the one positive, perhaps spurred by the extent to which he is missed by the public, is that for the first time, in a very significant way, a conversation by South Asians about depression is occurring – be it on social media, or around the dinner table. Aside from his film success, perhaps the legacy of the Bollywood prince is that just as he shone brightly in life, in death he has illuminated a very dark place in the South Asian community – one that needed desperately to be exposed.

SB Veda is the pen name for Sujoy Bhattacharyya who is a British/Canadian independent writer and contributing editor for this publication. His work has appeared in various Canadian and British publications including The Independent, The Guardian and The Ottawa Citizen. For long, he was a correspondent for Pragati, the oldest Indian newspaper based in North America.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine