Book Review: Anatomy of Life

By Pritam Bhowmick

Imagine a poet by the windowsill. The chic composure of his thought processes hurled out of the window. His inner sanctities staked on the peril of relentless and uncertain rediscovery. Confronted with the necessities of life’s turmoils, he ponders:

“The human self has come before all religions, nations and boundaries. What is the self? This is the question.”

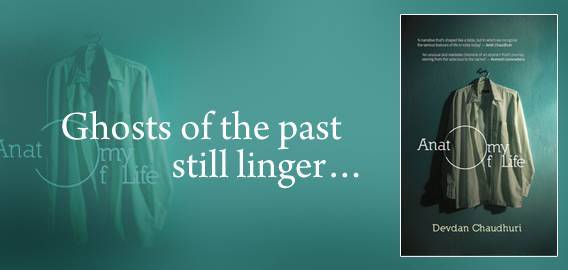

Rather than the dialectics of religion and nationalism, it is the interpersonal mode of subjection which propels the enigmatic protagonist of Devdan Chaudhuri’s debut novel, Anatomy of Life, to ruminate on his own individual system of actions, impulses, sufferance, governances and dispositions, straddling the frontiers of alienation and relationality.

In a novel peopled with spectral (rather than fully formed) presences etched out in a few traits, Chaudhuri introduces the reader to people named only by those characteristics: the poet, the sweetheart, the virgin, etc. These unnamed characters sketched sparsely rahter than fleshed out as actual human beings are circumscribed by but the poet’s existence, and rendered in the story only in terms of how they relate to him. The poet is the only protagonist, absorbing all shards of experience unto his self.

The triumvirate of time, self and experience interplaying against the seasons of the self are etched out chapter-by-chapter. The contours are somewhat lacking innovation, though, let alone provocation. His journey back home from college fraught with the redolent shadows of his deceased mother can only be his, seldom allowing the reader to penetrate the impenetrable veil of his mental ejaculations. The initial promise held out by the prospect of a young, eloquent man, unflinching in his examining of the precipices of reality evokes the Ulyssean quest,“to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”, It fizzes, though, out under melancholia of monstrous proportions, a repetitive mode of reflexive injunctions and solemn ordinances whose appeal wafts away with the smoke from the cigarette the poet lights in the toilet.

The elaborate excavation into the annals of (his) self-awareness, the gravitas indebted to the solipsist morality of an intellectual becomes a tad bit too much, though one must give credit to the author for achieving a certain lucidity even in the cumbersome expostulations of philosophical insights culled from eclectic sources.

Flitting in between girlfriends during his college years, vehicles for his consummation of lust and intellectual stimulation alike, he seeks out a stable configuration to his reflexes, a centre to the orchestrated chaos pervading empty space. The void is a recurring motif, though the eight page expostulation of its historical origin alongside modern scientific preoccupations with the peculiarity of the numeric zero seems a bit too grandiose for my taste.

Though existential absurdity and its obfuscations are a trope here, for all the supposed nothingness enshrouding the poet, he appears as suavely grappling with the naïve but affectionate sentimentality of a motherly aunt, of invariably resuming his ritual of morning cigarettes and coffee whilst de-cluttering the apartment haunted by the furnishings his mother had bought. The object that is being negated is never disowned. Remembrance…

The man of the world, sensitive as he is, is always keen on saving his skin, even while jostling against the crowds and waters of Kashi, one of the few places named in the book. “..He liked the sphere of the old city, because the theme of his self responded to its sphere”, vis-à-vis the reformulation of childhood memory and in fact, the recirculation of experience. His intellectual response to crises as he ambles across these experiential spheres (for example, that sphere dictated by his career choice of journalism) belies a pattern of defensiveness, sprung in part from the psychorubble of a divorced family in shambles. This behavioral trait is evinced in his initial engagement with his lovers, named as the Pianist, the Virgin and the Sweetheart. The poet’s father and especially his brother should have been etched out in a greater flush of detail to enforce the childhood of the poet in specificity.

Let’s return to Kashi, the politics of naming and representation notwithstanding. The poet’s intellectual response to the dawning of the urgency of imminent responsibility framed by the two parables mouthed by the boatman is to binarise the self and the cityscape, the latter being drawn up as the transitional space for “crossing over”. In the “privilege” of a new city, huddled alongside hippies, he conjures the mythical city as corrupt, destructive as well as preserving and transformative. Insofar as the domain sought out is closer to the “sense of timelessness and eternity” and beyond the value-laden dualisms of good and bad, the city acts as the counterpart to his realizations, which is attributed to his exoticization of the city. His intellectual progress is not without its share of epistemic violence.

The cycles of birth, living and death follow a trail of cosmological significance, disclosed as snippets of wisdom, jotted observations and explanations weaned from encounters. A profound awakening to ones mortality and transitiveness brings him closer to absurdity again, the absurdity of the lawyer confessing to his innocence of the case he was presenting. The wry acknowledging kind of laughter gives way to vast space laughing back at the dramatic solitude of man, of the inexorability of death stripping man of all entitlements. The free, “accommodated” self is reprieved of life.. In the midst of all this, the pet learns to cook, to meditate staunchly, avoiding unwanted phone calls from prying relatives. This routine, progressively developing in the novel, which emanates from his obsessive habit of journal writing, is a manifestation of what I call a “poetics of possibility” at work in the novel. In what could only be construed as an act of poetic injustice, none of his former lovers could comprehend that his fidelity was to his self-preservation, which till now had denounced empathetic understanding and renegotiation.

The sweetheart returns to the dream-world of the poet and then to his reality out of the blue. Her email conveying her singular devotion to the poet comes after a seven month silence in which she had been embroiled with a couple of men. The acute pragmatic distance accrued by her initially towards the poet’s reservations now seems to have placated for needing his love, nascent architecture of “a future” together. The poet retorts by asking her to refrain from contacting him again. She obliges.

The beautiful, a former friend the poet had defended from harassment in college, returns to the center again only to end up as another instrument in his perennial tussle between profitable wanting and independent wanting, to borrow Dostoevsky’s terms , or what remains of it.

He is a Cartesian being in motion. The transitory impulse embodied in life and in his own treatise on the anatomy of the body is pivoted on equilibrium, of curbing the intrinsic violence of the ego-self with the soul-self’s temperance, a journey from the human to the humane. It is only apt then that the clogs of the “wheel” return to family, or what remains of it. The search for absolution underpins the need to renegotiate torn dynamics, of exorcising ones self of the catastrophic impact of mutually abhorring parents on the children. Further inspection reveals the underpinnings beneath the embittered accusations of the past, that of disillusionment sprung from seeing their spouse changing into unrecognizable beings, lost in between the clarity of desire and turpitude of circumstance, husbands turned infidels, fathers into apparitions, beyond blame but never memory!

Coming full cycle, one realizes that the poets attempt to never fully invest into his relationships il likely a result of fear of reliving his mother’s, which remain open till the end..

The poet’s stepfather provides one area of delight in a novel drowning in a sea of solemnities. The poet’s mother falls in love with an old friend after twenty six years. If one could say that the novel culminates in the realization of choice, will constricted by reality, the stepfather, a poetry-enthusiast himself, chooses to die alone (of cancer) in the hillside residence of his friend. He is followed in by the poet’s mother the very next year. The poet finds love in the strangeness of another artist, stumbled across only incidentally in the hotel he was staying in, and the book ends with the sight of them mingling into the faceless anonymity of the metropolitan crowd.

Chaudhuri’s unmistakable gaze for the evanescent moments the self is in flux brings to the fore a delectable array of impressions, intensities that characterize the urban metropolitan life in its angularity and intricacy.

There are distinct points where a novice touch is evident, for there is hardly a page in this book without an awkward turn of phrase, redundant or strange combination of adjectives, even occasional issues with point of view. Take the following:” the sweetheart’s mother had acquired the ability to be unresponsive like a lifeless mass of stone” Right. Stones are lifeless – the simile works well without the added adjective. Instances such as this hit the reader over the head like a hammer. (Note I haven’t added the adjective ‘heavy’ but he might well have done so.) Here’s another: “at that precise moment, air condensed by the smell of dampness, heat and desire, was choked with the loud noise of religious prayer, amplified by an electronic sound device”. This is a contemporary novel – we’d know and the narrator would now that a speaker could amplify sound. Where he writes air is ‘condensed,’ I assume he means saturated or concentrated. The word condense doesn’t quite fit; it makes the reader think of condensation, especially with the mention of “dampness”. My point is that the prose lacks clarity and is overburdened with unnecessary language. This book purports to be a parable. The point puts me in mind of that famous book called Siddhartha by Herman Hesse, in which the style has an ascetic nature to it, paralleling the overriding theme of the novel. Chauduri has kept the characters as simple sketches and then overburdened the descriptions with unnecessary verbage. It doesn’t work, to my taste.

This book could have been a contemporary fable: enchanting read imbued with acosmopolitan feel, its confounding of the profane and the profound in one man’s existential journey. But Chaudhuri doesn’t quite pull it off. He is a promising and intelligent new voice in Indian fiction (and no doubt, we’ll be reading more of him) but debut effort while charming and philosophical, falls short as a narrative and exhibits ample room to grow.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine