Brexit: The Why and What’s Next

In the Aftermath Brexit – How It Happened, What’s Next

“It’s the right of MPs alone to make or break laws, and the peers to block them. So there’s no force whatsoever in the referendum result. It’s entirely for MPs to decide. The 1972 communities act is still good law and remains so until repealed. In November, Prime Minister [Boris] Johnson will have to introduce into parliament the European communities repeal bill,” – Geoffrey Robertson, Queens Counsel

By Narada Roy and SB Veda

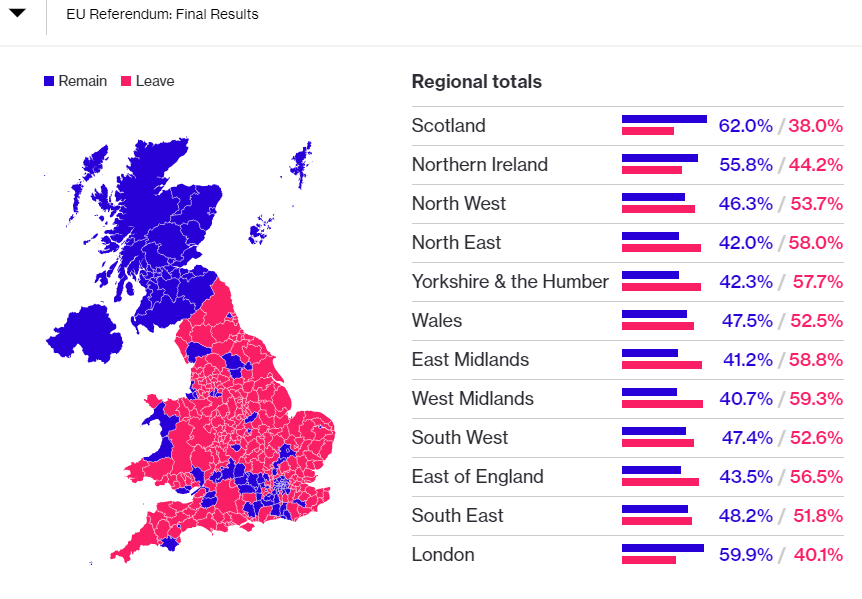

Young educated Londoners were in tears mourning the loss of Europe last Friday after Britain voted 51.9% to 48.1% to leave the European Union (EU). This contrasted with older jubilant working class people from such places as Manchester and the Midlands who hailed the result as an ‘independence’ vote. Scots, who voted by a margin of 62% to remain felt outraged and thoughts of a new referendum on independence were not far from their minds. All the while, major newspapers in the UK like The Guardian and The Times were calling it an ‘earthquake.’

As some imagined a stronger, more independent Britain, others foresaw a poorer crueler country in the aftermath of the referendum. The optics around the recent vote by UK Citizens by a margin of 2 percent to leave the European Union, are chaotic to say the least – and turmoil ensued.

From Japan to Europe to the New York exchanges, losses of approximately three trillion dollars hit international assets as a result of the surprise result, last Friday before rallying somewhat by Tuesday. Another measure of investor anxiety is the abrupt tumble in the value of the pound. The British currency experienced its steepest one-day drop in history on Friday, losing around ten percent of its value against the US Dollar. It too has rallied but remains below pre-Brexit levels.

It was not just the implications across the wider Eurozone to which investors were reacting. A convincing majority in Scotland (62%) and Northern Ireland (55%)(not to mention over 95% Britons in the UK territory of Gibraltar) voted to remain in the EU. This contrasted with England and Wales, where majorities of just 3 and 2 percent (accounting for a margin of around a million votes) tipped the scale in favour of the Leave campaign. And so, United Kingdom found itself divided by country. But the divisions didn’t end there: London voted by a margin of ten percent to remain whereas migrant-rich areas such as Manchester and the West Midlands voted to leave.

In fact, the electoral map represented a clear North-South division, leading to cries for Scottish independence and anxieties in Northern Ireland at the prospect of a hard border between it and the Republic of Ireland.

Already, Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish First Minister, has planned to travel to Brussels to talk about protecting Scotland’s interests and its will to remain, though she backtracked from earlier comments that the circumstances in which Scotland would be forced to leave despite voting to remain, would lead to another referendum on independence.

Recent polling indicates that a slight majority of Scots would support independence if the UK split from the EU. The prospect of another political fight so soon after the referendum looms menacingly for Westminster politicians who will be in-charge after Brexit (so far, it’s not clear who will be replace Prime Minister David Cameron and whether Labour Party Leader, Jeremy Corbyn survives a massive Labour MP revolt); the scenario of an independence vote would only add to the disquiet.

The last battle over Scottish independence was waged two years ago when Scots voted by a margin of 5% to stay in the Union. Back then, Scottish economic prospects were much better as proponents of independence thought they could sell Scottish crude for over $110 a barrel. Today, with the price of crude being only $40/barrel, a compelling argument can be made that Scotland would be worse off without the rest of the UK – even if it remained in the EU.

Still, economic arguments don’t always persuade. Scots have long preferred the power of London to be checked by Europe. The new Prime Minister (whomever s/he may be) may well have to wheel and deal with Scotland while negotiating with Europe. As Britain negotiates to stay in the common market, the new PM may well have to give up cede more ground to the Scottish Parliament before all the talking is done.

Boris Johnson, the leader many credit with breathing new life into the Leave campaign and whom many had thought would vie to succeed David Cameron as Prime Minister, did little to ease the uncertainty. He has said the UK should be in no rush to invoke Article 50 of the EU Constitution, which would begin the process of splitting. With calls for a new referendum gaining momentum, the waiting is only adding to the uncertainty. Finance minister George Osborne concurred.

In his latest column, for the Telegraph Johnson painted a rosy scenario in which Britain remained in the common market but was not shackled by EU bureaucracy or liable to pay an annual fee to Brussels.

“British people will still be able to go and work in the EU; to live; to travel; to study; to buy homes and to settle down. As the German equivalent of the CBI – the BDI – has very sensibly reminded us, there will continue to be free trade, and access to the single market,” Johnson wrote.

The rest of the EU may well be unwilling to deal, preferring a hard line in order to dissuade other nations from leaving. Already, right wingers in Germany, Holland and France, have called for their own referenda on the EU.

Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor has said that while the UK should be given some time to adjust to the vote, this should not take too long. She also ruled out negotiations prior to the UK formally applying to split by invoking Article 50 refers to the Treaty of Lisbon, which amended the Treaty of Rome and the Maastricht Treaty and sets out the process by which nations may split off from the EU. She added the UK could not ‘cherry pick’ during negotiations on spitting off from the EU.

“We will make sure that negotiations will not be carried out as a cherry-picking exercise. There must be and there will be a palpable difference between those countries who want to be members of the European family and those who don’t,” Merkel stated on Tuesday.

As though responding directly to Johnson’s weekend Telegraph article in which he said Britain would still be permitted access to the common market, Merkel added: “Whoever wants to leave this family cannot expect to shed all its responsibilities but keep the privileges. Those, for example, who want free access to the single market will in return have to respect European basic rights and freedoms … that’s true for Great Britain just as much as for the others.”

CONFUSION ABOUT WHAT COULD HAPPEN

Further muddying the outlook is the fact that the Brexit Referendum is not legally binding on Parliament; it is simply advisory as to the opinion of the electorate.

Queen’s Counsel, Geoffrey Robertson, told British newspaper, The Independent, that there is no immediate impact of Brexit. In order to leave the EU, Parliament must first repeal the act, which permitted the UK to join the EU in 1972. He added that Parliament may not be in a position to repeal that act until November when the impact of Brexit becomes clearer.

“Under our constitution, speaking as a constitutional lawyer, sovereignty rests in what we call the Queen in parliament,” he told The Independent.

“It’s the right of MPs alone to make or break laws, and the peers to block them. So there’s no force whatsoever in the referendum result. It’s entirely for MPs to decide. The 1972 communities act is still good law and remains so until repealed. In November, Prime Minister [Boris] Johnson will have to introduce into parliament the European communities repeal bill,” Mr Robertson said.

“MPs are entitled to vote against it and are bound to vote against it, if they think it’s in Britain’s best interest [to vote that way]. It’s not over yet.”

George Osborne, UK Chancellor stated, in his first public statement since the referendum result, “Only the UK can trigger Article 50. We should only do that when there is a clear view about what new arrangements we are seeking with our European neighbours.”

It is the Prime Minister’s prerogative to invoke the article, and David Cameron has left that up to his successor. If it turns out that Johnson comes to occupy 10 Downing Street after Cameron, it could be a long time before this is done, given his recent statements.

Europe has had a mixed reaction to the vote. While some European leaders have urged haste such as EU Parliamentary President, Martin Schultz, who said, Britain should, “Deliver now…and the Tuesday summit is the most appropriate time to do so,” others like German Chancellor, Angela Merkel have urged caution and deliberation: “It shouldn’t take forever, that’s right, but I would not fight for a short timeframe,” she said.

Indeed, there is no legal limit on how long the UK can wait before Parliament invokes the article. The article states that the exit negotiations would take up to two years but can be extended if all the EU countries agree unanimously that they need more time.

The continuing uncertainty have caused markets to fluctuate. Investors like stability, and react by selling off when during times of uncertainty or increased risk.

“No political stability was seen over the weekend,” Anthony Darvall, chief market strategist at spread-betting firm easyMarkets, said in a note Monday morning.

Markets continued to plummet throughout the day. In the United States, the Dow Jones industrial average and Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index fell more than 2 percent before recovering some ground, and he tech-heavy Nasdaq floundered by 2.4 percent. London’s main FTSE 100 index was down 2.6 percent while Germany’s DAX reduced more than 3 percent.

After Friday’s dramatic sell-off following the result of the vote, investors were probably reacting, Monday to the downgrading of the UK’s “AAA” rating to “AA” by S&P Global Ratings. In their report, S&P remarked that, “the outlook on the long-term rating is negative.”

“In our opinion, [Brexit] is a seminal event, and will lead to a less predictable, stable and effective policy framework in the U.K.,” stated the S&P Reprot. Fitch Ratings followed with its own downgrade and revised down its forecast for the growth of Britain’s gross domestic product through 2018.

THE HOW AND WHY OF BREXIT

Roots of Eurosceptisicm

The unexpected result of the Brexit Referendum have left many asking why Britain would undo forty years of growing European association. The answer combines old feelings with new circumstances.

Political debate on Europe has historically contained a good measure of Euro-scepticism. Matthew Goodwin of the University of Kent, who has studied the phenomenon and written a history of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), concluded that Euroscepticism is not only political but also cultural in the UK. Britain, he has written, “forged its identity against perceived threats from across the Channel,” adding, “although the young and better educated tend to be less Eurosceptic, the popular notion that it is only older working-class voters who favour Brexit is not correct.”

That said, it is older Britons who remember the then British Empire going it alone against Nazi Germany, liberating France while other European nations either opposed them or stuck their head in the sands of neutrality. The alliance with the US during the war cemented the notion that when Britain needed a reliable friend, the nation had to look across the Atlantic rather than the English Channel to its European neighbours.

It may come as ironic then that it was a war-mongering British Prime Minister who envisioned Europe, post WW II as a potential of United States. In 1945, Winston Churchill encouraged reconciliation between France and Germany, proposing the two take the lead in creating the union but he did not envision a role for Britain.

In 1951, The European Coal and Steel Community was created, brought into force by the Treaty of Rome, to reflect the beginning of this vision. Wary of the association, and wanting to preserve ties with the commonwealth and the United States, Britain declined invitation. Instad, the UK sent a mid-level trade official as an observer at signing of the treaty with the leadership of the Kingdom staying away.

A decade passed, and France and Germany were making steady post-war recoveries while war-torn Britain struggled. Conservative Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan felt that continued exclusion would see Britain left behind, so he applied for membership in 1961. Eurosceptics, like Labour’s Hugh Gaitskell, who said a year later that joining a federal Europe would be “the end of Britain as an independent European state, the end of a thousand years of history”.

Macmillan’s application was vetoed for a decade by French president Charles de Gaulle, who feared that the UK would cause the tapestry of the union to unravel. This was not taken well by Britain though the membership application was not withdrawn. It was not until 1973 that Edward Heath’s Tory government took Britain in, with Labour hugely split.

With his party containing the most high profile sceptics Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson tested the issue of membership with a referendum. Then, the Tories stood solidly behind membership (unlike the split in the party that was observed in the Brexit campaign) and the UK voted by two thirds majority in favour of membership.

It wasn’t long before Euroscepticism crossed party lines. The undercurrent of exceptionalism swelled to a tide in 1988 when the European Commission’s president, Jacques Delors, promised the Trades Union Congress that Europe’s single market would be burnished by tougher labour and social regulations. This reinforced Prime Minister Thatcher’s growing Euroscepticism, and led directly to her Bruges speech attacking excessive EU interference in the same year.

“We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels,” Thatcher said during her 1988 speech in Bruges.

The right in Thatcher’s party were persuaded that the original vision of a trading area had been supplanted by Franco-German ambitions for social, political and economic union. As the centre of gravity shifted in both main parties, Labour under Neil Kinnock embraced a social Europe, albeit with resistance from unions and the left. Thatcher’s increasingly strident scepticism put her at odds with key members of her cabinet, including Michael Heseltine, and hastened her downfall.

With Thatcherite skepticism defeated, for the time being, her successor, John Major signed the Maaschricht Treaty under which significant transfers of power to the EU took place. The UK managed to secure opt-outs from the single currency and the social chapter. But to the treaty’s critics – including many Tory rebels – it undermined the British tradition of the inviolable sovereignty of parliament. And, Major was undermined, thereafter, at every turn by people in his own cabinet. He famously called three key Cabinet Ministers “bastards.” And, as the EU became more socially oriented and integrationist, the Eurosceptic camp in the Conservative party grew.

As Tony Blair’s New Labour embraced Europe though old-style left wing sceptics remained in the party. During his tenure as Prime Minister, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown pushed back on the UK adopting the Euro, despite being pro-Europe, himself. He had deep reservations about the currency, and doubts about the European economy.

Despite joining in 1972, Britain never fully accepted the legitimacy of European control over British institutions in a way that other EU members did. It refused, for example, to join either the Schengen Area, which eliminates internal border controls, or the common currency. To the rest of Europe, it seemed a sweet deal but to many UK citizens, the notion of a supranational entity dictating policy, making rulings that apply domestically, and creating a new layer of bureaucracy that through which the UK would be compelled to navigate, was and remains highly unpalatable.

Recent Events Undermining the EU

These are historical pangs that have grown over time. Added to this are two key events, which took place over the past eight years:

The first is the global economic crisis of 2008. Both the USA and Europe were hit hard by the crisis. While the US Federal Reserve took decisive action to rescue the economy in America, The European Central Bank (ECB) was slow to react by contrast. When it finally did, the bank increased interest rates, which did more harm than good.

Europe slipped into a double digit recession as Greece faced bankruptcy. The situation deteriorated to such an extent that Greece seemed poised to drag Europe down in the process.

Alhough the UK was largely unaffected, having stuck to the pound, the crisis heightened fears that the Eurozone was a risky economic playing field. With EU’s tendency to expand its power and bureaucratic inertia, many wondered whether it was inevitable that Britain became bound to bail out lesser economies that had been wrecked by poorly crafted EU policies.

Then there was the crisis in the Middle East. The rise of ISIS and war in Syria caused waves of refugees to seek asylum in Europe. Merkel, quite compassionately, decided to open Germany’s doors to the refugees. However, critics complained her actions were not properly thought out, because it ignored inevitable forces pulling migrants to where their prospects were better: the sudden influx of asylum-seekers disrupted people in their everyday lives across the EU but most sharply in richer countries.

While Britain opted out of being a party to the Schengen agreement and fully dismantle border controls with other EU countries, EU law still requires members to admit an unlimited number of migrants from other EU countries. Already with the Eurozone suffering from dismal economic performance, a lot of workers from less affluent EU states like Poland, Bulgaria and Portugal moved to the UK in search of work.

But the apparent lack of adequate controls on refugees coming to Europe led to a panic, affecting everyone: the local population, the authorities in charge of public safety, and the refugees themselves. It has also facilitated the rapid rise of xenophobic anti-European parties – such as the UKIP, which spearheaded the Leave campaign – as national governments and European institutions seemed incapable of handling the crisis and the UK Parliament lacked the authority to exert control, having given up that power.

For several years, a perception has lingered in the minds of many Britons that migration has adversely affected the economy. It hasn’t just been influx of poor people. Eastern Europe’s rich were drawn to the prestige of London. The result is that Russian oligarchs and the like have bought up much real estate in London, driving housing prices up, preventing many first-time home buyers from affording their own domicile. For this reason, while mainly older Britons voted to leave, a block of young people did the same, hoping the housing market would adjust as non-British Europeans leave.

David Cameron Gambled and Lost

When David Cameron campaigned for the Tory leadership in 20015, it was on a promise to lead the party out of the centre-right federalist grouping in Europe called the European People’s party (EPP). The ostensible anti-Europe bent was a sign of intent: to be on the side of Eurosceptics. But Cameron was never really one of them. Whether it was calculation or cowardice, he chose a path of appeasement rather than to confront the isolationists in his own party over Europe.

He promised to impose austerity on the EU, to negotiate and veto further plans for integration. For the Eurosceptics in his party, it wasn’t enough.

After winning the 2010 UK elections, Cameron initially tried to move his party away from divisive fights over Europe. He wanted the Tories to stop “banging on about Europe,” as Cameron once famously put it. Increasingly he saw ruminating on the EU as a distraction from pressing domestic issues – and knowing the subject had led Thatcher’s downfall and Major’s marginalization, he wanted to move on.

In this he failed to succeed, hammered from both outside and within his own party as his political situation became increasingly tenuous. His austerity policies halted Britain’s economic recovery, leading to a slowdown in growth between 2011 and 2012 sending his poll numbers tumbling. The ongoing eurozone crisis amplified Tory critiques of Europe, and continued EU immigration fueled the rise of the anti-EU, anti-immigrant UK Independence Party (UKIP).

According to Vox, in May 2012, “Cameron convened a meeting of his advisers — at, of all places, a pizza joint in Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. They decided to run a play straight out of Cameron’s 2005 playbook: throw a rhetorical bone to the Euroskeptics without actually trying to alter Britain’s relationship to the EU. That meant a referendum on Europe.”

In June 2012, Cameron proposed something along the lines of the discussion that fell short of Brexit: a vote on whether the EU should try to negotiate a different deal for its membership. The proposal was met with derision from Eurosceptics within his party as being watered down, and it sent alarm bells off in the British Parliamentary establishment.

Friends and political allies like Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg asked Cameron why he would make such a comment. He responded by saying he was compelled to halt the rise of the right within his own party and UKIP on the outside.

“I have to do this. It is a party management issue. I am under a lot of pressure on this. I need to recalibrate,” Mark Kettle of The Guardian quoted Cameron as saying. “My backbenchers are unbelievably Euroskeptic and UKIP are breathing down my neck.”

What seems strange to many is that, at this point, Cameron faced no formal rebellion here. He put the whole association with the EU at risk simply as a political tactic. In doing so, he fell into the classic appeasement trap. The Eurosceptics wanted more, and feeling that Cameron perceived the fight as one for his political survival, they pressed their advantage. “From that moment the issue became when, not whether, Cameron would pledge a referendum as Tory policy,” Kettle wrote.

What seems strange to many is that, at this point, Cameron faced no formal rebellion here. He put the whole association with the EU at risk simply as a political tactic. In doing so, he fell into the classic appeasement trap. The Eurosceptics wanted more, and feeling that Cameron perceived the fight as one for his political survival, they pressed their advantage. “From that moment the issue became when, not whether, Cameron would pledge a referendum as Tory policy,” Kettle wrote.

In January 2013, Cameron formally committed to holding a Brexit referendum if the Tories won a full majority in the 2015 elections. Cameron did not expect to have to follow through on this — most UK political observers believed the Tories would either lose or, at most, win a plurality of seats in Parliament. His position, though, managed to keep UKIP at bay and put Labour on back footing. He was to be a modern day Icarus, burned by his own success, winning back-to-back majority governments for the Tories for the first time in 23 years.

He’d given himself a timeframe of up to the end of 2017, and went to work on Europe. But he found a chilly reception across the Channel to his demands. EU leaders such as Germany’s Merkel wanted to help him make the case to stay in the EU but they, too, were also distracted. The unprecedented amplitude of the waves of migrants flooding into the Continent and the aftershocks of the Greek debt crisis was sprouting opposition to the EU in their own countries. Faced with a newly formed and mounting opposition to Europe at home, other 27 EU countries were reluctant to create different rules for the U.K. In particular Merkel torpedoed Cameron’s efforts to put forward a British exception to the EU’s freedom of citizens to work and live anywhere in the bloc.

Cameron felt he had no choice but to compromise. His advisers were eager to get a deal with Brussels and hold a referendum sooner than later. Delay would in their view carry higher risks, they’d calculated. Another year of negative stories about the Continent “would absolutely destroy” his chances of winning a vote, he was told by senior figures in the Remain effort.

Relenting to the pressure, Cameron dropped his election commitment to deny benefits to migrants for four years in return for something else to help curb immigration. In the end, Britain would get an “emergency brake,” allowing the U.K. to withhold access to benefits for new migrants for a one-off period of seven years.

While Cameron thought it to be a good deal, he was crucified in the press. “It flopped, but it was sort of impossible to meet expectations,” the adviser close to Number 10 said. “[Cameron] thought he got a good deal, but for people who cared about the deal there was no deal that was ever going to be good enough.”

The Stronger In campaign to remain would craft a clear message and focus on the economy. That message would underline the risks of leaving, and try to win the argument early. They wanted to pin the Leave side to fighting on immigration, where they thought it would come off as negative, xenophobic, and divisive.

“What we wanted to do early on was own the economy, own business, and own the fact that you’ll be better off [by voting to stay],” a senior campaign source said. “We wanted to own that very early. And I think that was successful, because that sort of pegged them back to another kind of campaign, which is essentially the [UKIP leader Nigel] Farage campaign. Which is very, very focused on immigration, very, very focused on isolating Britain from the world. Now, that is a powerful argument and has its impact, but it’s not what I think the people who were originally running Vote Leave wanted.”

Stronger In developed their message for months before officially launching the campaign, giving them a head start over the Leave campaign. The result was a slew of clearly understood messages: “stronger, safer and better off” in the EU, and leaving would be a “leap in the dark.” Both tested well with focus groups.

With an early ten point lead in the polls, it didn’t much trouble the Remain campaign that their ally, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn refused to campaign with Cameron. Despite former Labour PMs Blair and Brown requesting the current leader to extend a hand across the aisl, Corbyn was adamant. He felt deeply and personally betrayed by Cameron that after cooperating with Cameron’s Tories in the Scottish referendum, Cameron hit him hard in the election campaign over Scotland, contending that a vote for Labour is really a vote for a coalition government with the Scottish National Party. The scare tactics proved successful and Corbyn was bitter.

The Remain campaign even contemplating drafting US President Barak Obama to convince Corbyn to be more cooperative during a trip to London in April. Labour aides advised them not to bother – Corbyn’s position was intractable, and the idea died before reaching the White House.

But Cameron did seek Obama’s help in April. The U.S. president’s somewhat nuanced statements on the benefits of ‘sticking together’ were welcomed by Cameron, though critics considered them profoundly hypocritical. His intervention in April did encouraged more young people to register to vote. Other statements were counterproductive: “We have a phrase in America: ‘Friends don’t let friends drive drunk,'” he said, adding that it would be “a big mistake for Britain to leave the EU and set asunder what has been a very successful relationship,” Obama said to the dismay of many. He went on remarking that Britain would be “at the back of a queue” for a trade deal with America if it left the union. The two statements, in particular, irritated many U.K. voters.

It didn’t help him that high profile Conservatives like Boris Johnson, former mayor of London (and a popular one at that, despite frequent impolitic speech) regularly hammered Europe in his columns for the British daily, The Telegraph. Johnson had cut his teeth in journalism, reporting on Europe from Brussels, and had been an early Eurosceptic.

That Johnson’s articles were funny and contained what many perceived as ‘common sense’ reasoning, made him all the more dangerous for Cameron. A case in point is an article he wrote back in February, in which he ridiculed European bureaucracy:

“The more the EU does, the less room there is for national decision-making. Sometimes these EU rules sound simply ludicrous, like the rule that you can’t recycle a teabag, or that children under eight cannot blow up balloons, or the limits on the power of vacuum cleaners. Sometimes they can be truly infuriating – like the time I discovered, in 2013, that there was nothing we could do to bring in better-designed cab windows for trucks, to stop cyclists being crushed. It had to be done at a European level, and the French were opposed.”

For Johnson and his ilk, the EU interferes far too much in what should be the sovereign domain of the UK but remains unaccountable to the people – fundamentally, undemocratic.

But Johnson was an old friend and ally of Cameron’s; they’d known each other from Eton and Oxford, and texted each other regularly. So, in February, when MP And former two-time mayor of London lent his considerable political weight the Leave campaign, it came as a shock – a betrayal that cut deeply. “There is huge frustration and a feeling of betrayal with Boris that feels very personal for Cameron,” a source close to the prime minister said. Until the day of the result, the pair had not spoken in months.

Cameron lost another political ally and close personal friend to the other side: Michael Gove, the justice secretary and Godfather to Cameron’s late son Ivan. Their wives were friends and their children played together.

“[Cameron] had been led to believe Michael was onside,” one former Downing Street aide said.

Instead, Gove had joined the charge for Brexit two days before Johnson, after months of agonizing between his loyalty to the prime minister and his fiercely Euroskeptic convictions. He and Johnson made a strong combination.

Johnson’s many TV appearances and his presence as mayor of London during the 2012 Olympics had turned him into a genuine celebrity. He was regarded by the media as the most popular politician in the UK. Tracing a path tirelessly around the country in a red bus, his enthusiasm and personality “single-handedly transformed what was an oddball group of pretty unattractive people” into a mainstream political force, a former senior Conservative adviser said.

Johnson’s closing speech in a BBC TV debate, two nights before Thursday’s vote, in which he declared June 23 Britain’s “Independence Day,” was one of Leave’s strongest moments in the campaign, the source said. “I truly believe that that may have been one of the most significant reasons why we went over the top last night,” the Leave source said on Friday.

“He was believable, he was passionate, he gave everyone who was watching it a very clear message: Here’s why you should vote for us,” the Leave insider said. “Then there was inspiration at the end. Those are all the critical components to motivating a voter to go to the polls to vote for you.”

In contrast, he said, the politicians on the Remain side were all about fearmongering. They were “dark, they made it personal, they didn’t make it about the people of Britain and I think that hurt them tremendously.”

Cameron’s pitch of “stronger, safer, and better off” proved to be less memorable than Vote Leave’s “Take back control.”

Stronger In had underestimated public anger about Cameron’s broken promises on controlling the flow of people from the Continent, and amongst the message-crafting, all the slogans, they didn’t have a convincing argument to counter the backlash.

Remain were “surprised and impressed” by how well Vote Leave exploited the public’s dissatisfaction with the large number of EU citizens who had come to live and work in Britain, one senior source said.

It wasn’t just the focus on migration that led to the surge in support, a Leave campaign source said. They sought to turn voters’ concerns about it into a positive pitch: If you take back control from Brussels, you can end free movement across borders and relieve the pressure on hospitals and schools. The aim was to reassure voters it was no big deal to back Brexit. Their politicians were well-drilled, and stuck to the script. In one hour-long TV appearance Gove used the phrase “take back control” 23 times.

Remain failed to “make the case that life for people in Britain was going to be better remaining in the EU,” said a Leave campaign insider. “They just made the case that leaving would be bad. There’s a big difference between those two things.”

Stronger In watched in frustration as the Leave count rose in the polls. “They said they wouldn’t, but their whole fucking campaign has been based on immigration,” one staffer said.

They didn’t think the bounce for Vote Leave would last. “I can’t believe people are really going to vote themselves poorer because they don’t like the Poles living next door,” one former Cameron adviser said at the height of the Brexit surge.

Yet in the second week of June, Leave was ahead in most published polls.

In a last ditch effort to gain support from Corbyn and Labour among whose constituents, older white voters, who didn’t like Cameron, seemed confused about Labour’s position on Brexit. Swaying these voters, particularly in the marginal and rural areas might well have held the vote to Remain. But Corby defiantly campaigned on his own – and that, in lackluster form leading some familiar with the leader to conclude that his heart wasn’t in it.

His recalcitrant attitude to Stronger In coupled with his lacadasical performance on the stump, have led to a huge rebellion in his own party. 172 members have called for his recognition, and he has recently lost a confidence motion on his leadership. Again, defiantly, Corby chooses to remain – as leader. And, so he has another fight on his hands when all UK political parties should be coming together to chart a course for the future.

Could anyone have predicted a bigger mess?

WHAT HAPPENS NOW AND OVER THE NEXT TWO YEARS?

In short – nobody knows what will happen. What can only be painted are scenarios in which some are more likely while others are more remote.

Parliament Could View the Referendum as ‘Advisory’ and Simply Disagree with the ‘Advice’

Setting aside the referendum results because it has no legal weight is a risk proposition for any elected official. That said, MPs are entitled to vote their conscience. If they feel it is in the UK’s best interests to remain in Europe despite the slim majority of Britons who indicated, last Thursday, that they wanted out, it is their duty to do so. They may risk their political fortunes but, in the end, may sleep better at night.

Still, in the UK, the people don’t get to decide everything, even important things by direct democracy. The Parliamentary system is premised on the notion that elected officials will do what is in the best interests of the citizenry – and that Parliament, constitutionally, can only bring into force the will of the people. In Britain Parliament – not the average person is sovereign. And, that’s a reality that may well save Britons – from themselves.

Holding a Second Referendum

There was talk from the beginning to hold a referendum on a new deal with Europe. Should the EU agree to advance negotiations, a deal could be worked out, and this could be voted on. The other EU leaders could still be afforded the right to play hardball with the UK. People in the Remain camp might welcome it, virtually assuring the opposite result in a second referendum.

Should Europe not wish to negotiate even unofficially, the UK could still hold a second referendum. The notion was proposed by petition of which over 2 million have signed. The US through Secretary of State John Kerry has already expressed support for such an idea – that in this way, Brexit could be “Walked Back.”

Indeed, many who voted for the split are already having ‘buyer’s remorse.’ Prominent Brexiter, Sean O’Grady expressed his doubts in a recent article for The Independent.

“Even for an optimistic Brexiteer like me, the last few days have been difficult. Many people who voted out are already feeling a bit betrayed as certain fundamental truths sink in. The “uncertainty” is already affecting the real economy as we see,” O’Grady wrote.

He added: “Before long this uncertainty will feed through even more concretely from the slightly abstract world of financial markets and exchange rates through to jobs, savings, and, above all, the value of people’s homes, which is where most people’s wealth is stored (especially some of the less well-off voters who opted for “Leave”). This is really why I suspect Brexit won’t, in the end, come to pass – because most voters can’t afford it in the short run, whatever the longer term advantages.”

He remarked, too the mandate was too slim to decide such a fundamentally important issue: “The margin for Leave was pretty small, in reality,” He wrote. “…and so the mandate is weak. Most countries have a constitutional convention that big changes have to command a two-thirds vote in a legislature or referendum, and this was nowhere near it.”

Hold an Election

This would be tantamount to the Tories committing hari-kari as, post Jeremy Corbyn (assuming he is pushed aside) Labour would surely win a mandate to rule as the champion of remain and also advocate of the working class. The fact that Cameron and other Tory politicians have called for Corbyn to step down, indicates that an election may well be in the offing.

If Gove or May loses to the next Labour leader, might it make room for a Cameron comeback – or perhaps Johnson would jump into the race instead of keeping his feet wet after a Conservative defeat.

Under a new government with Brexit at the centre of an election campaign, Labour could handily walk Britain back from the brink. The Tories are hemorrhaging anyway, they might as well do themselves in for the good of the country, say some analysts.

Invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty

This would be doubling down on Cameron’s original wager. The new PM could commit to a referendum on the result with a commitment from EU Leaders that the process could be halted if Britons choose they don’t like the alternative to remaining.

Invoking the article would get the EU to the table – but there are huge uncertainties in doing so.

People like Boris Johnson (who has just announced he would not be seeking the Prime Minister’s job) would say that Britain is too important to Europe for the other leaders to cut the UK out of the common market. At present, though, there seems no political will to extend that accommodation. At some point, Brussels is bound to draw a line at Britain’s exceptionalism. And, emotions have run high after Brexit.

The most likely outcome in the end is for the process to drag somewhat while the other EU leaders take a hard line, and Britain’s economy worsens in the continuing uncertainty. This would make it popular to set aside the result or hold a new referendum.

In the end, it might be much a do about nothing with an equally Shakespearian end to the illustrious career of David Cameron.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine