Charulata – A Classic Revived

Fifty Years On, Ray’s Masterpiece Remains Affecting, Poetic

By S.B. Veda

In cinema, the word ‘masterpiece’ is perhaps overused; still, it seems somewhat lacking when applied to Satyajit Ray’s film Charulata, which was digitally re-mastered and re-released on the big screen by RD Bansal Productions and the British Film Institute (BFI) to an extended run, this past week. The BFI Southbank is running a retrospective on Ray, which began on August 15th, and will run until October.

I rarely write on film as, though my regard for the medium is fulsome, my understanding of it is hardly scholarly. That said, I cannot resist writing about Charulata, especially as I am editing a book by one of Ray’s contemporaries in which Ray’s own hand sketches for this film with notes to his cinematographer, Subrata Mitra, are included. Looking over Ray’s drawings and thoughts on how Charulata should appear on screen, gave me new insight into Ray’s method of storytelling, which for this film comes through almost exclusively through sight and sound rather than spoken word.

This year marks fifty years since the film’s release, and it is not the least bit dated. The opening scene, comprising some ten minutes of running time and containing hardly any dialogue, is told mainly in the movement of images. In fact, Ray’s work in Charulata can be described as pure poetry in motion, strikingly vivid on screen, now, in HD.

It opens with protagonist Charu, knitting embroidery for her husband in a bedroom – we only see her fingers slipping a needle and thread through a handkerchief as the credits roll. Ray’s musical rendition of Kazi Nazrul Islam plays in the background: a string instrument plucks the tune sparsely, the melody then taken over by a flute as the sliding strings of the sitar unmistakably complement it. The camera pans up to her face and moves back, expanding the shot as the opening credits conclude, and we see Charu for the first time, portrayed beguilingly by Madhabi Mukherjee.

She is knitting a crest with the letter ‘B” on it, what we can only assume is the first letter of her husband’s name. Later, this is confirmed when we find out his name is Bhupati. She is clearly bored, dangerously so – shouting at a servant, shooing away a bird; then, finished the embroidery, she tosses the handkerchief listlessly aside on the bed.

She notices a book, pouncing on it to leaf through its contents. It does not engage her. Returning it back on the shelf, she runs her fingers playfully over the covers of the other books, picking one out, then another, to read it while walking back down the stretching corridor.

Yes…she reads on screen with only her intermittent humming to accompany the act. Ray is probably the only film-maker who is capable of creating tension in this way – who else would dare put someone on screen, shot from the back, walking slowly, book-in-hand without uttering a single word, and endeavor to carry it off?

As Charu reaches the end of a long veranda, she is distracted by the rhythm of a noisemaker or Doogdugy coming from the street outside. The makeshift percussion instrument, a small drum with a ball attached to a string, striking it as it is shaken, is playing vigorously in the hand of a monkey trainer – leash in his other hand.

As Charu reaches the end of a long veranda, she is distracted by the rhythm of a noisemaker or Doogdugy coming from the street outside. The makeshift percussion instrument, a small drum with a ball attached to a string, striking it as it is shaken, is playing vigorously in the hand of a monkey trainer – leash in his other hand.

She peaks through the wooden blinds of a large window to see the man with the monkey in the distance, and rushes back to her bedroom, pulling out opera glasses from a drawer. Dashing back to get a better look at man and beast, the camera follows only her horizontally striped sari moving through the vertical balusters of a long veranda. The flow of her movement is perhaps one of the most aesthetically interesting shots of a woman walking, ever. Reaching the window, she can only catch him exiting her field of vision. Clearly disappointed, she turns her attention to other passers-by, flitting from one window to another.

Each time, rays of light slice into the room, dissecting her as a human being, from her surroundings, which keep her restrained like the monkey on the leash. Ray goes further: his shots are framed through pillars, balusters, shuttered windows, bedposts – all connoting prison bars. She lives in a mansion but is a captive of circumstance. The black and white footage emphasizes the contrast as bright rays of light pierce the darkness of the large empty rooms. And the culture dynamic of British modernism on Indian tradition has begun in the Bengali mind.

The lonely wife walks back to her bedroom, and standing in the doorway hears her husband open a door and enter the scene. For the first time, we realize that she is not alone in this seemingly empty house.

Bhupati, wearing suspended trousers and a white shirt, a pipe dangling from his lips, passes her engrossed in his thoughts, entering his library. She hesitantly inches towards the room, clearly craving some form of meaningful interaction but is perhaps fearful that her presence will interrupt his work. Before she can enter. He returns, giving her a second pass without so much as a glance, evidently finding the book in his hands more interesting than his wife.

Charu, opera glasses still in her hand, raises them to her eyes to peer at her husband – only to see him, in the distance, turn at the end of the long hall and plod down the stairs. It is at that moment in a close-up of her that we realize what she has come to understand, that Bhupati is as much a stranger to her as the passers-by, outside, for she is Chaurlata: the lonely wife.

There are but a few sentences of dialogue in this entire sequence – and the words are incidental to the story-telling. The plot moves forward only in the movements of Charu and the motion of the camera. Still, in those opening minutes, Ray, without a word spoken between them, cements the relationship between Charu and Bhupati in our minds. In this, Ray exhibits true cinematic genius accomplishing what few are able to do: telling the story perhaps more vividly through moving images, sound and music, than through the exchange of speech – words seeming to be too clumsy a medium for a tale, which is best absorbed intuitively through the lens.

There are but a few sentences of dialogue in this entire sequence – and the words are incidental to the story-telling. The plot moves forward only in the movements of Charu and the motion of the camera. Still, in those opening minutes, Ray, without a word spoken between them, cements the relationship between Charu and Bhupati in our minds. In this, Ray exhibits true cinematic genius accomplishing what few are able to do: telling the story perhaps more vividly through moving images, sound and music, than through the exchange of speech – words seeming to be too clumsy a medium for a tale, which is best absorbed intuitively through the lens.

The use of opera glasses, through which Charu studies the world outside (instead of say binoculars) is telling. What she absorbs through them is mere theatre: it cannot be real, lest she give into circumstance. In the end, she must see and face the reality of her life for what it is, this without her optical aid by which she keeps her surroundings at a distance. She is forced, ultimately, to see the situation ironically up-close, and with more acuity through her own eyes. And then, her world becomes irrevocably altered.

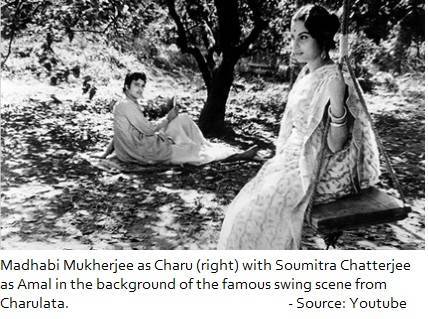

Adapted from a novella called ‘The Broken Nest’ – Nastanir in Bengali, written by Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, the story is one in which scant action occurs, unfolding rather in the triangular relationship between the three main characters: Charu is the neglected wife, intelligent but dispirited by her surroundings; her husband Bhupati (played by Sailen Mukherjee) runs a newspaper, and is consumed by the issues of the time – principally, the struggle for Indian independence even as his persona, dress and habits are unmistakably British; his cousin, would-be writer, Amal, played with characteristic poise by Soumitra Chatterjee, blows into their lives like a gust of wind (literally during a wind storm) upsetting the delicate balance of their household.

Madabhi’s Mukherjee’s acting is almost telepathic – as it has to be, really, for the film to be effective. We crave knowledge her thoughts as so much of the conflict takes place inside her mind – and she delivers, her portrayal being composed of subtle expressions, measured movements. Even in stillness, her disposition, the way she stands, sits, carries herself, conveys more than what most actors could manage with a lengthy soliloquy. So utterly complete is her rendition, expressive yet voiceless at times, that one wonders how well she would have done in the silent era.

Her performance plays off of a lively Soumitra Chatterjee without whom the story does not happen. His Amal embodies possibility with charm and energy, and encourages Charu to pursue her intellectual and cultural interests. Theirs is a love that smoulders but never catches fire. How could it within the social mores of the time? Still, the proto-feministic theme that a woman could rightly want and need more than tending to house and home comes through definitively.

The camera work of Subrata Mitra is outstanding. Through Mitra’s technique, Ray gives us an steady flow of meaningful images with striking clarity, which can be appreciated all the more in the restored version. There is the memorable scene with Charu, telegraphing her thoughts as she sings while sitting on a garden swing, rocking to and fro like a pendulum – at first out of frame, and then we join her swinging in the shot; another when she falls on the bed unable to contain her pain with the camera making a swift half-turn enabling us feel her dizziness without getting gimmicky – both of which are technically difficult, brought off precisely, subtly and most of all, effectively.

The camera work of Subrata Mitra is outstanding. Through Mitra’s technique, Ray gives us an steady flow of meaningful images with striking clarity, which can be appreciated all the more in the restored version. There is the memorable scene with Charu, telegraphing her thoughts as she sings while sitting on a garden swing, rocking to and fro like a pendulum – at first out of frame, and then we join her swinging in the shot; another when she falls on the bed unable to contain her pain with the camera making a swift half-turn enabling us feel her dizziness without getting gimmicky – both of which are technically difficult, brought off precisely, subtly and most of all, effectively.

Ray uses song in the tradition of Indian film to raise the level of emotion to that beyond which words can express (for this pearl of wisdom I must credit film scholar and Ray contemporary, Father Gaston Roberge, SJ); this is especially important in this film in which so much emotion lies beneath the surface. At the same time, he never gives in to Bollywood kitsch.

The film’s underlying theme of suppressed passion quivering on the precipice of expression is counterpointed both on a personal and political level: Bhupati and his ilk see possibilities for self-rule in India in the Liberal victory at Westminster in 1880; this chance at Sadhinatha (independence) is reflected in Charulata herself – a bright, talented woman yearning for deliverance but sliding silently, unwittingly (in today’s cinema – inevitably) towards betrayal.

In Ray’s Charulata as in Tagore’s Nastanir, the betrayal lies in the realm of mind and heart rather than action, though this is damaging enough. Amal perhaps sensing the natural conclusion of wants set in motion, leaves without a word – and like everything else, the betrayal, too is repressed.

But the feelings break free in a storm at the end. After Amal’s departure a letter comes, and the emotional amalgam of angst and anger comes bubbling up to the surface. A tempest violently gusts into the room, breaking a glass as tears stream down Charu’s face. Bhupati having witnessed the display rides off in a horse-drawn carriage, for he too cannot contain his tears – we see that he can feel pain, love, regret; and when he brings the handkerchief away from his eyes, he sees the letter ‘B’, which Charu had embroidered in the first scene of the movie. Ray has deftly brought the story around to the first scene – only so much has changed; the plot has gone full-circle.

The final shot in the film – a freeze-frame close-up of Charu and Bhupati’s two hands reaching for one another – preserves eternally the possibility of their reconciliation. With the drone of the Tanpura playing, the caption “Nastanir” – Broken Nest appears, leaving the lingering question, is it irreparably broken – or do the outstretched hands signify that the attempt to repair is definitive in itself?

Bengali cinema is rife with psychodrama but in none since has done it been portrayed so effectively as in Charulata. Ray himself regarded it as his finest film, containing “fewest defects” as he put it in his characteristically self-deprecating way.

In addition to directing, Ray wrote the screenplay and is credited with the film score. Spoken words are sparse, but the dialogue is layered, and to really understand the subtext one must be familiar with Bengali. A scene comes to mind in which Charu is addressing Amal, and she breaks from the formal and appropriate use of Apni to Tumi – both mean ‘you’ in English but unless one is somewhat conversant in Indian languages, one cannot grasp the significance of the change in vocabulary. Subtitling in French, which would have substituted tu for vous in that scene, might well have captured it – but I have not seen a French subtitled version of the film. The film score is also mostly minimalistic but Ray relies on the musical instruments to convey sentiment, which the characters themselves are bound to keep inside. A lesser film-maker would not have been capable to render so complete a vision of his work as the multi-talented Ray.

While the film remains a beautiful work of art – lovely to look at, especially after the restoration, and as relevant fifty years later, in viewing it one must make adjustments: in this age of quick cuts, short scenes, and snappy dialogue, Charulata does not ‘pop’ – nor should it; it is we who ought to slow down to really absorb its content. Even with these adjustments made, one may (as I did) find some scenes a bit too theatrical, melodramatic even – but infinitesimally so, compared to contemporary Indian cinema. In that way, Charulata, half a century after its debut, is far ahead of its present-day counterparts.

The re-mastered version, digitally touched up by RD Bansal Productions (the original producer and stalwart of Bengali avant guard Film) was screened at Cannes, last year. This follows the restoration done in 1994 by Merchant Ivory productions (Ishmael Merchant having been the driving force behind it) with the involvement of Martin Scorcese and Ravi Shankar. The new version of the film is wonderfully restored – better to look at than the original, appearing in HD – its images so crisp and clear, it seems to have been shot, yesterday; this, while preserving the signature period black and white.

The film won Ray the prestigious Golden Bear for directing at the Berlin Film Festival (his second) but was inexplicably ignored at Cannes. He won many awards, including 32 National Film awards in India, The Dadasaheb Phalke Award (the Indian Film Industry’s highest honour), Best Documentary at Cannes (for Pather Panchali, with Palme D’or nominations for Parash Pathar, Devi Ghare Baire and Uttoran– but not for Charulata), 3 Golden Lions from The Venice Film Festival, and an Honorary Oscar in 1992 just before his death. He is regarded by film historians, without any notable exception, as being among the best film-makers of all time – and Charulata is arguably his best film. It is a work of art that affects us as all as great art must do. After the final scene, we are left feeling like Charu through most of the film: wanting.

If there is one film you see this year, let it be this one.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

For those, like me, who are used to seeing Ray’s films in bad print, this is truly magnificent to see it so perfectly polished. And, Charulata is maybe Manikda’s best film. I really liked your review as well. You write better than many so called film critics. Well done.

The original truly stands the test of time. I like it so much better than the remake, which was garbage in comparison.

I was hooked on Ray’s films since Marty Scrocese was involved with Merchant ivory to restore and re-release some of them in the nineties. This is a great film, and the review makes me want to see it again. Excellent work!

This film shows that sometimes what is unsaid is more powerful than what is said. BTW, the author did a wonderful job of depicting the opening scene. It was really vivid story-telling, and reminds us of Satyajit Ray’s genius.

This is probably the best adaptation of Tagore on film. What an amazing combination, when the work two geniuses are fused together to make art. It is truly phenomenal beyond words as is this terrific review. I’m a great fan of the writing on this blog. You should submit it for awards. I’m sure you haven’t yet because yo’d be bagging a handful, I am sure.

Your “re-visit of Charulata” is wonderfully depicted. I have no words to express the beauty of your review. I agree with other commentators that you should submit your review for awards.

This review left me wanting as you so aptly put it, that I immediately bought a copy of the film! Your piece so much better than the other reviews online, you should be getting a piece of the profits! Send your work to the Newyorker, next time. Seriously!

Your review depicts poetic expression of art rather than any critical comments. I am sure Ray would have loved it if he was alive and Madhavi, who is my maternal aunt would have certainly loved it too. Please send the review to Madhavi in Calcutta.

Thanks. There is a paragraph on it seeming too theatrical, and requiring adjustment on the part of the viewer to appreciate the deliberate way in which the story is depicted. The New York Times in its original review of the film in 1964 said it proceeded at “a snails pace”, though overall the review was positive, so one can imagine how today’s audience, especially those unfamiliar with the film-making style at the time would react to it, today.

Also, if I’m not mistaken, Madhabi is your cousin by marriage, your cousin-brother, himself being a renowned actor, Nirmal Kumar. I did meet Madhabi at the Kolkata Literary Meet where we were both delegates but we are not in touch. Still, I hope she does manage to happen upon the review as it rightly lauds her spell-binding performance. Without a strong Charu, the film has no legs – SB Veda.

No doubt, this film is a masterpiece but what a surprise to find such great writing comimg out of Calcutta Thus is a review worthy of Pauline Kael, Roger Ebert et al, Beautifully written with insightful analysis. Ive never heard of you, SB Veda but Im sure I’ll be reading more of your work.

Wow! Thanks Arthur and to all for your kind words. It comes as great encouragement!

I hardly read any review on films and I’m not even a frequent viewer of films. But I did see this film and not once but multiple times in the past. My love affair with this film made me read your review. At first, I decided to read only a few lines. But oh boy, you made me read all of it, and with much interest. It’s an excellent review article by all means. Keep on going SB Veda, we need you.

Many thanks for your kind words of encouragement; helps make the effort seem worthwhile!

One corregendum. Subrata Mitra is the name of the famous DOP not Mukherjee.

Thanks for that. It has been corrected. We welcome any comments you might have on the content.

Reviews on Charulata by SBVeda was amazing,had seen the film long ago, recently read again the story so I enjoyed reading his review today throughly . Veda’s description can be made for audio book as the description is so vivid. Well done , sure expecting lots lots from you in future. Congratulations, keep up the wonderful work you are doing and hope oneday we will read your novel and will get B. prize.