From Spy to Whistleblower: Snowden’s Permanent Record Illuminates as it Alarms

by SB Veda

” The myriad of ways in which we are willing accomplices in our own surveillance and electronic incarceration boggles the mind. And, if nothing else, we are left with a strong sense of how privacy, currently not an explicit right in any nation, including the United States. should be at the heart of public advocacy.”

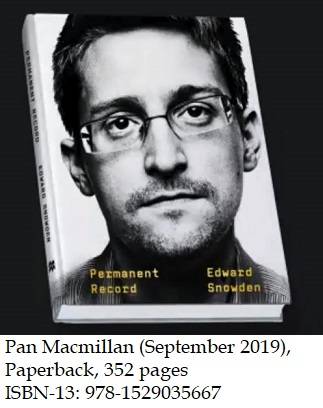

Edward Swowden’s memoir, Permanent Record, begins with the defining dialectic of his life: “I used to work for the government,” he writes. “Now I work for the Public.”

Exiled in Russia since 2013, the then twenty-nine year-old contractor for the National Security Agency (NSA) and former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) employee never imagined that six years later, he would still be unable to return to his home in the United States of America. To be sure, should he enter, he would be charged with crimes under the Federal Espionage Act under which, if convicted, he could go to prison for decades. It’s hardly the path envisioned by the scion of a civil service family.

In an age when every second person thinks their life story is the compelling stuff of memoir, Snowden’s universally intrigues. It is understandable too that after rumored attempts to negotiate a deal with the US Government facilitating his return failed to obtain any tangible result, Snowden may be hoping to appeal to the public at large to tell his side of the story.

For those who expect a thriller, the book will not engage those dopamine receptors. The former hacker’s nerdy nostalgia over Nintendo and the Commodore 64 home computer tend to be a bit much early on. However, Snowden’s family history and his upbringing gradually provide a pretty transparent window into his mind, including the psychology behind the decisions he made. He was hardwired from childhood to believe in the idea of service to one’s country, a kind of patriotism that supersedes loyalty to the state administrative apparatus.

The book traces Snowden’s ancestry directly to the Mayflower. Indeed, in some places, the family name is synonymous with the land, itself. Even today, Snowden Fields in Maryland is cut by Snowden River Parkway. The author tells us not without some pride that his family members fought on both sides of the Civil War (though not before emphasizing that the southern side had abolished slavery on their lands almost a century before President Lincoln mandated it). Indeed, one member of his family or another has served in every war in which the United States has been involved (even before the place was known as the United States).

“Mine is a family,” he writes, “that has always answered the call of duty.” We are, therefore, meant to extrapolate this to Snowden’s life – or at least to his decision to expose the NSA mass surveillance program on an unsuspecting public.

In deciding to join the army post-911, it is natural to of young Snowden answering a call of duty. However, following his parents’ painfully abrupt divorce, which came towards the end of high school, he characterizes it as a small act of rebellion. Both his father and maternal grandfather had worked for the Coast Guard and held the army in low regard. Feeling the need to explain, Snowden slipped a note under the front door of his father’ apartment (after the split, Edward was living with his mother).

Reminiscences of basic training at Fort Meade aren’t exactly scintillating narrative but his injury and subsequent transition into the Intelligence community in the area of Systems Administration and Engineering sets the stage for what is to come.

As we follow Snowden through circular path of becoming NSA tech contractor to CIA tech analyst to, once again, contractor, this time at technology bunker at the NSA in Hawaii, he recounts his increasing unease how electronic data collection and management in the US government occurs, especially the extent to which public networks are essentially in the hands of private contractors. At one point, he writes, “The NSA may have paid for the (computer) system but sysadmins (sic) like myself were the ones who really owned it.” Interestingly, according to Snowden, the civil service managers who manage the contracts are not aware of how the US government’s networks overlap, interact and where their gaps lie. He also reflects on the system of contracting as being inherently corrupt, citing how his salary was arrived at when he was initially hired as an example. The contractor was paid on a percentage plus salary basis, and so, despite communicating a salary expectation of $40,000, the contractor agreed to pay him $63,000 in order to increase the company’s own profit margin, taxpayer be damned.

The corrupt nature of contracting led him to join the CIA as employee, exchanging his “green badge for blue,” as he puts it. Hoping to be deployed to the ‘War on Terror,’ he is punished for standing up for his colleagues by being handed a posting in Geneva. Advising operations directors on how to snoop on the international diplomats and banking officials was not at all why he joined the CIA. So, he allows himself to be volunteered to an intelligence operation to co-opt a Saudi banker, which went horribly wrong. Later, sticking only to signals intelligence and systems administration, the more he learned the more did his faith in government erode.

A stint in Japan an American air force base where apparently, the NSA pacific headquarters is located (talk about American imperialism) follows. It is here that he first comes across the NSA’s mass surveillance program quite by accident. The knowledge soon becomes his own personal albatross and he finds himself on short term disability leave, stateside, suffering from seizures and depression. A new and rather cushy job at a huge signals intelligence repository on the island paradise of Hawaii where the pace of life is lax, seems just what the doctor ordered. But, as Snowden recounts, acquiring information came as second nature, coming from a hacking background. And, he finds confirming evidence of his Japan discovery. That’s not all: the secret domestic spying program more pervasive than he initially understood. So, during perhaps his happiest time of life, he is faced with a confounding moral choice – does he sit on this – or do something about it? Of course, what he does is a matter of history, now.

Unlike many such stories, there is no one tipping point. Snowden’s was a gradual evolution from blind nationalist to skeptical patriot. Given his background and upbringing, the choices he made aren’t all that surprising. Certainly, testimony given by US Director of National Intelligence James Clapper just two months before his momentous decision – that the NSA doesn’t “wittingly” spy on US citizens (a baldfaced lie) – must have been impactful on an increasingly distressed Snowden.

Here he reveals his thoughts and spends not an insignificant amount of space drawing distinction between leaking and whistleblowing, even going into the history of the term and activities exemplifying it.

It takes almost two-hundred and fifty pages before Snowden reveals one of the book’s most significant truths: that he need not have sacrificed his life as he knew had the media actually done its job. Two months before Snowden copied classified documents and fled the United States for Hong Kong, the CIA’s Director of Technology gave a lecture at a public technology conference, which was set up for live pubic streaming, and was subsequently uploaded to YouTube. In it, he told anyone who’d listen that the US Intelligence Community (IC) was in possession of technology to collect copious amounts of data through means about which the public was woefully unaware. And, worse still, that they were actively availing of it.

Snowden quotes this individual (nicknamed Gus) with an appropriate sense of irony: “At the CIA we fundamentally try to collect everything and hang on to it forever…It is nearly within our grasp to compute on all human generated information.” This was two months before Snowden felt compelled to reveal the details to the press.

Even more damningly for the media, on the heals of his lecture, Gus gave a second talk to journalists in which it was revealed that the government could track smartphones even when they were turned off, and that the CIA could surveil every single communication made through these devices. Surprisingly, he challenged journalists to do their jobs in this respect: “Technology is moving faster than government or law can keep up. It’s moving faster than you can keep up: you should be asking the question of what are your rights and who owns your data.”

Snowden recalls being “floored,” for anyone more junior than the speaker, revealing such information would have resulted in firing at minimum, possibly prosecution. But journalists’ eyes were too glazed over by that point to grasp the importance of the revelation Gus had just given them. And, not a single quantum of informed reportage appeared on blog coverage or in newspapers, the next day.

The experience explains why Snowden not only resolved to blow the whistle on the IC but also the manner in which he did. He chose two journalists in Laura Poitras and Glen Greenwald, who were unlikely to ignore overlook the significance of the evidence he was planning to share – and they had a record of standing up to pressure coming from powerful places. This was an essential requirement after the government quashed a New York Times article that touched on the same surveillance program about which Snowden informed. Still, there was a missing element that he decided to apply – he needed to train and educate the journalists, almost become a partner in reporting, before it could successfully stir an anesthetized public.

By now, one is well into Part III of the book, and a sense of tension is building. Snowden’s description of how he copied highly classified documents and liberated them from the confines of the secret military bunker turned NSA IT hub in Hawaii gets the heart pumping. He recounts driving around to hack public networks using a GPS antenna and self-erasing laptop to get in touch with journalists. At the same time the story moves despite Snowden’s less than thrilling prose style. While the narrative here is focused on how Snowden managed, under the nose of America’s most intrusive and capable spy agency, to steal their secrets – and escape, it is rife with sentences like –“I struggled with how to handle the metadata situation;” and, “That’s the incomparable beauty of crytpological art” – hardly the stuff of John LeCarre.

Storytelling stumbles aside, Snowden’s book is, hands-down, the most important biography written this decade – and anyone who doesn’t want to live in a digital police state should read it. The myriad of ways in which we are willing accomplices in our own surveillance and electronic incarceration boggles the mind. And, if nothing else, we are left with a strong sense of how privacy, currently not an explicit right in any nation, including the United States. should be at the heart of public advocacy.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine