Long Island: Where past and present intersect but fail to connect

“In the hallway, she looked at the telephone on its stand. If there was one number she could call, one friend to whom she could recount the scene that had just been enacted at her front door! It wasn’t that the man, whatever his name was, would become more real if she described him to someone. She had no doubt that he was real. What she wanted was someone to offer an interpretation of what had happened that would give her some consolation. At the moment, she herself could see none.”

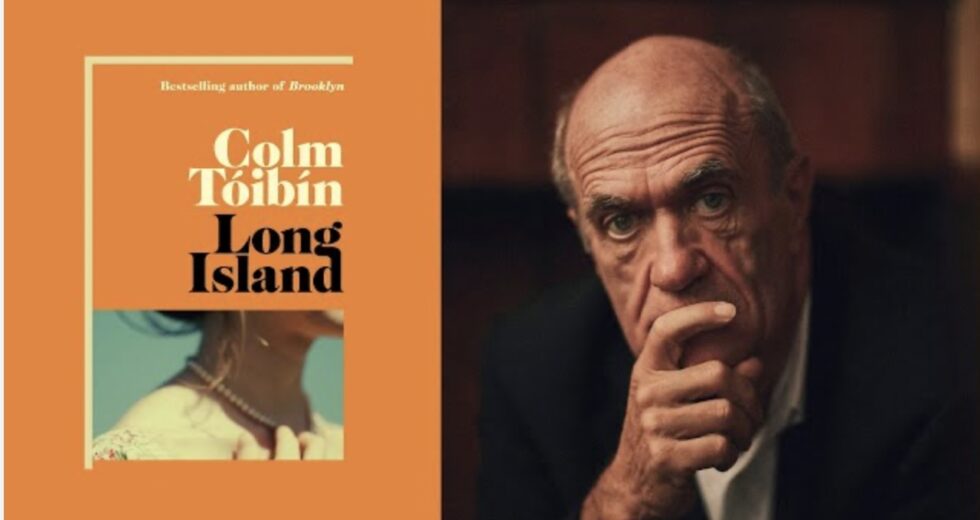

Review of Long Island by Colm Tóibín

by SB Veda

When a sequel can read as a stand-alone piece of work, the narration is uncommonly strong as is the case with Colm Tóibín’s Long Island, a sequel to his acclaimed novel Brooklyn, taking place some two decades after the original story.

I am among the few who read this book without having read the progenitor but could have been none the wiser had I not known it was a sequel.

In a way, it is refreshing not to know the backstory as the way in which Tóibín reveals it is light and enticing. At the outset, we need not know what happened to the protagonist, Eilis, an Irish émigré to America, living in Long Island, who is the wife of an Italian American plumber named Tony with three brothers and a dominating mother – a family that shares a cul-de-sac built for them, so they could be close to one another. Eilis and Tony, by now, have two children, one teenager and another on the cusp of becoming one. For all will be revealed, in threads and knots.

Publisher : Picador (Pan MacMillan, 23 May 2024)

Language : English

Length : 303 pages

Eilis is smart and strong-willed. While she keeps the books for the family plumbing business in which all but one brother works (the odd one manages a good education at Dartmouth and becomes a lawyer, far removed from the family neighbourhood) Eilis decides to take a similar job with a the owner of an automobile garage who is close with her in-laws.

Before we are able to comfortably settle into Eilis’ domestic life, one that is made obtrusive by the proximity of the extended family to her home. Eilis is the only non-Italian in the mix, and so feels an outsider. The fact that her in-laws can practically “see through her windows” into her house and life is particularly suffocating. Still, while her life would ordinarily be filled with the daily escape of her job, the growing pains of her children, and the family politics of Sunday lunch, the homely edifice suffers a car-bomb of an explosion with the news that Tony, while on one of his plumbing jobs, had a brief affair with another Irish woman, and managed to leave behind his seed.

Indeed, in the opening pages of Long Island, the husband of the adulterous woman shows up at the family home to deliver the news to Eilis with the addendum that once the baby is born, he will be delivering it to their doorstep to raise as he will not bring up another man’s child. That he is also of Irish extraction makes the situation especially awkward in that, Eilis “had known men like this in Ireland.” She understood the man’s adamance in refusing to raise a “plumber’s brat” and believes to her core that “he means to do exactly as he says”.

The revelation leaves us in medias res, creating immediate tension.

At first, Eilis quietly digests this shattering news, going about her day with the secret simmering inside of her. Then, when it boils over and she confronts Tony, she wants to know what he intends to do only to find out that the news has already been shared with the other family members and Tony’s mother wants to raise the baby in her house.

While she cannot bring herself to say the words, this is not something Eilis can accept. She doesn’t want the living evidence of her husband’s infidelity (his only one, she and we are meant to believe by Tony’s assertions) living in an adjacent home and enjoying the bosom of a family that is meant for her and her children. She discounts that her children may wish to interact with a half-sibling and can focus only on the notion of sharing her husband with this outcome of betrayal.

She decides she needs a break from Long Island, and as her mother is turning eighty in Ireland, plans a trip there. Her children, both out of curiosity (they have never met their Irish relatives including their grandmother) and a desire to escape their awkward circumstances plan to join Eilis, once she has settled in.

It is clear that Tony would consider going as well if asked but he doesn’t broach the subject. After all, he has a child on the way and must decide what to do about it. Tony asks her if she is coming back, and without quite saying it brutally, makes it clear that it all depends on what Tony decides to do about the baby. She would be able to forgive him, she thinks, if he gives up the child for adoption.

We soon find out why she is so willing to forgive him. His is not the only infidelity. Indeed, shortly after Tony and Eilis were married while she was visiting America from Ireland, she returned briefly to Ireland and had a relationship with a barman named Jim – much of the plot of Brooklyn.

This was no fling: Jim was about to propose to Eilis when she abruptly returned to the United States without so much as saying goodbye. The relationship with Jim was like a parallel life more than an affair – and the marriage was kept secret. When her Irish friends came to learn she’d married an American, it was assumed that this had happened only after Eilis had gone to America the second time. Nobody knew then that she’d been married in secret before returning to Ireland but the truth has its way of penetrating lives.

By the time Eilis arrives back in Ireland, she finds that not much has changed in the small town of Enniscorthy from which she had fled only to come back and take refuge: Jim, never married still runs the bar; her best friend Nancy, though widowed by now, runs the chip shop that her husband owned. The one main difference is that Jim and Nancy are a couple and planning two weddings: Nancy’s daughter’s and their own.

Eilis’ return isn’t the shattering blow to Jim and Nancy’s comfortable domesticity that Tony’s infidelity is to Eilis’ but it is inconvenient as it stirs up old feelings, brings up unfinished business, asks unanswered questions. These come up everyday life: trips to the market; a walk on the beach; culminating in Nancy’s daughter’s wedding.

The parochial town from where Eilis hails is not one conducive to personal privacy, and stories are told, re-told, and spread. She is the shadow that makes an already dreary town darker.

Despite the rekindling of the fire inside of her for Jim, she is no longer the twenty-year old gal who can grab what’s right in front of her. She has learned from her own life that impulses have consequences. And, those consequences can cause pain.

Jim’s longing for Eilis, which comes up from the moment he sees her on the street risks his betrayal of Nancy. Even Nancy herself, unaware of triangle that dominates Jim’s feelings, is caught up in one herself, for even as she wants to move on and marry Jim, she cannot help feeling that she is betraying the memory of George her departed husband.

Long Island is the story of small deceptions, quiet secrets that begin small, even microscopic but their denseness make them ignite like atom bombs in each character, affecting them profoundly and irreversibly. The tension in the novel tightens in what is not said, what is not done, and the knowledge that, ultimately, this cannot go on. An ending is in sight, but it cannot be happy when the desires of one are bound to result in the pain of another.

Toibin’s domestic dance of repression of feeling is elegantly depicted, and the story told in close-up narrative third person, which tightly reflects each principal’s point of view. In depicting the inner lives of characters who he left behind fifteen years ago, Toibin has completed a story that is brilliant in its narration of ordinary lives that portrays the extraordinary feelings embedded in its ordinary characters. It is living, at its most mountainous and flat. It reflects the fact that one cannot feel at home in a place that is not their own nor can they fully return to the home that they left. Only a master can find the phenomenal in the common of the lives of those represented in Long Island – a place that begins front and centre but, in the end, hangs in the background.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine