Review of Poker Face

Poker Face Has a Sting in Its Tail

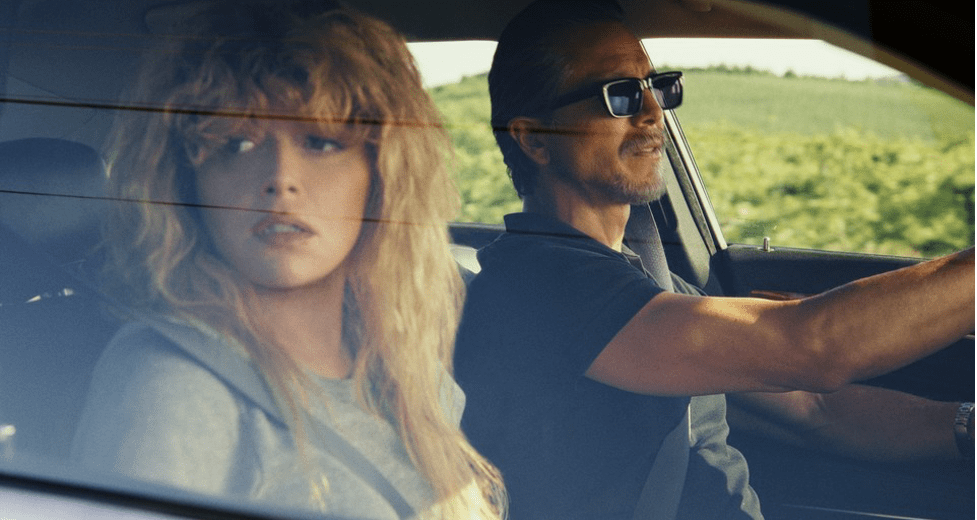

Natasha Lyonne is extremely fun to watch as a crime-solving waitress on the run.

From The Atlantic.com

By Sophie Gilbert

JANUARY 26, 2023

What I tend to want in a crime drama is to be enveloped in atmosphere from the very first frame, and on that count, Poker Face delivers.

The new, impeccably credentialed Peacock series, from the director Rian Johnson (Glass Onion, Knives Out) and the actor and writer Natasha Lyonne (Russian Doll), begins in the hallway of a Las Vegas hotel. The creak of a service trolley and the hallucinatory swirls of a carpet evoke a sense of low-grade panic.

Inside the presidential suite, a maid (played by Dascha Polanco) sees something on a guest’s laptop screen and freezes in horror. The score throbs with percussive menace. As an introduction, it has everything: sharp intrigue, familiar stylistic tics, a promised peek into the murk of human iniquity.

And this is all before Lyonne arrives playing Charlie Cale, as buoyant as a Labrador—if Labradors smoked and drank and holed up in rusty trailers in the Nevada desert with elderly Elvis impersonators for company. Poker Facehas been touted as its creators’ take on procedurals from the 1970s and ’80s such as Columbo and Murder, She Wrote—shows anchored by lovable stars whose disheveled outerwear and argyle knits were as much a selling point for viewers as the weekly mystery. It’s a killer setup. There’s scarcely a person on this Earth as charismatic as Lyonne, as rumpled and chaotic and fun to watch.

In Poker Face, Charlie isn’t a cop. This suits the current skepticism toward stories that unquestioningly valorize policing, but it also makes her more vulnerable—just an average, unarmed person without backup, confronting murderers about their crimes. The only authority she has comes from her unofficial superpower: Without knowing why or how, she can tell when someone is lying and when they’re telling the truth, a skill that she utilized briefly as a card shark until things got too dicey. Her gift is actually less useful than it might seem, because, as she explains, everyone is lying all the time.

Lyonne’s last major project, the deeply personal Netflix series Russian Doll, was a giddily strange and inventive investigation of trauma as a family legacy. Johnson’s previous projects, the genial detective movies Knives Out and Glass Onion, revived a format that had long felt stale. Pairing the two feels like alchemy, and the show’s entwinement of light and dark, of artistry and ham, makes the best installments of Poker Face feel superlative. At the end of the first episode, Charlie is forced to flee her job as a cocktail waitress and go on the run, bounding stop by stop into the micro-communities of the highway. The show draws on the breadth of Johnson’s and Lyonne’s connections—guest stars include Adrien Brody and Chloë Sevigny—but each story is buttressed by Charlie’s presence. In some episodes, I got impatient for Lyonne to arrive. In others, the introductions were as thrilling as one-act plays. Johnson’s stamp as the director of the first two episodes is hard to overstate: He makes ugly landscapes seem beautiful, blocks interior scenes with an artist’s eye, and emphasizes the fluorescent, antiseptic feel of shared liminal spaces. (Never has a Subway seemed so aesthetically interesting.)

But: The danger in making what’s essentially an anthology show with a recurring character is that patchiness will abound. Early on, Poker Face avoids pastiche by attending to the emotional cadences of overlooked people and places—the kids crushed by boredom working menial jobs in the middle of nowhere, the women in hotels who clean up the intimate detritus left behind by guests. At one point, Charlie, arriving at an isolated rest stop in her broken-down car, meets a trucker named Marge (the recent Academy Award nominee Hong Chau), who schools her on how to live off the grid: “No phones; no bank accounts; fake IDs if you can get ’em, but better to stick where people aren’t askin’.” She’s a character so immediately rich that she risks making everyone else insipid by comparison. She also betrays the ingenuity of the people who plotted Poker Face out, and their unironic appreciation for this particular genre.

In later episodes, a handful of characters felt to me more like tropes than fully baked ideas: a failed rock star, an aging TV actor reduced to doing dinner theater, two spiky rebels waging war in their retirement community. I don’t want to be unappreciative, because in renovating the crime procedural so persuasively, Johnson and Lyonne are making clear a truth that’s largely been forgotten in the undisciplined era of streaming: Structural constraints can be liberating for storytellers. The formal boundaries of certain genres can force writers and directors to focus on the essentials, and innovate between the lines.

When watching popular procedurals, you accept certain things without question, because the setup is just so fun. Better not to wonder why Jessica Fletcher, a humble novelist, finds death everywhere she goes, or how Columbo persuades every single criminal to stick around for his one last thing instead of hightailing it out of town. On Poker Face, it’s easy to forgive the fact that Charlie often accidentally nudges people toward their imminent fate, or that the show’s vision seems rather cynical, with the do-gooders invariably getting bludgeoned by the devious schemers. Nor did I really mind what felt like abundant product placement, if only because brands are so intrinsic to the American road that it’s impossible to imagine that particular landscape without them. Seeing Charlie, like a shaggy chameleon or a chiller Forrest Gump, blend seamlessly into any conceivable situation is a thrill. Rural barbecue stand? She fits right in. Merch table at a skeezy dive? No one’s better. Retirement home? She’s mastering shuffleboard and raiding the lost-and-found box for flip sunglasses—at least until someone tells a lie that catches her attention

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine