Short Story Master Wins Booker for Debut Novel

“In the US we’re hearing a lot about the need to protect culture. Well this tonight is culture, it is international culture, it is compassionate culture, it is activist culture. It is a room full of believers in the word, in beauty and ambiguity and in trying to see the other person’s point of view, even when that is hard.” – George Saunders

SB VEDA

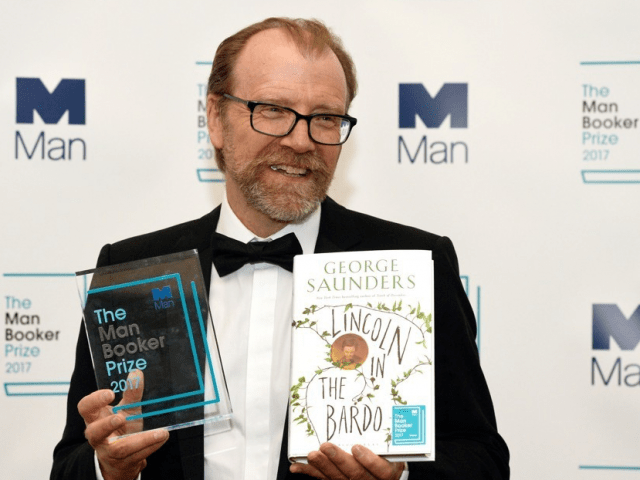

Embracing the unconventional, the Man Booker Prize judges, this year, have awarded one of the World’s most prestigious literary prizes to George Saunders for his dreamy, emotional, and uniquely stylized novel, Lincoln in the Bardo. Saunders is the second American to win the prize, which was only open to authors from Britain, Ireland and the Commonwealth of Nations until 2013, after which it was also opened anyone writing in the English language. The first US Citizen to win was Paul Beatty, who won last year for his book, The Sellout, making the 58 year-old Saunders the second consecutive American to win the coveted literary prize. He was in contention for the prize with two British, one British-Pakistani and two American writers.

Upon announcing the winner, Lola, Baroness Young, 2017 Chair of judges, commented:

‘The form and style of this utterly original novel, reveals a witty, intelligent, and deeply moving narrative. This tale of the haunting and haunted souls in the afterlife of Abraham Lincoln’s young son paradoxically creates a vivid and lively evocation of the characters that populate this other world. Lincoln in the Bardo is both rooted in, and plays with history, and explores the meaning and experience of empathy.’

For Saunders, the judges’ decision was an profound validation of his foray into full-length novels, having previously navigating the realm of the short story and novella.

Lincoln in the Bardo focuses on a single night in the life of Abraham Lincoln: an actual moment in 1862 when the body of his 11-year-old son was laid to rest in a Washington cemetery. Strangely and brilliantly, Saunders activates this graveyard with the spirits of its dead. The Independent described the novel as ‘completely beguiling’, praising Saunders for concocting a ‘narrative like no other: a magical, mystery tour of the bardo – the “intermediate” or transitional state between one’s death and one’s next birth, according to Tibetan Buddhism.’ Meanwhile, the Guardian wrote that, ‘the short story master’s first novel is a tale of great formal daring . . . . [it] stands head and shoulders above most contemporary fiction, showing a writer who is expanding his universe outwards, and who clearly has many more pleasures to offer his readers.’

The story is apparently based on the real-life visit of Lincoln to his son’s crypt in Georgetown where he is said to have cradled the boy’s corpse in his arms. Lincoln is known to have described his son, William Wallace (Willie), who having succumbed to typhoid fever at the tender age of eleven, as “too good for this world,” and “better off in heaven.” His love and remembrance of Willie was so pervasive that he had talked about the boy during his carriage ride to the theater on the evening of his assassination.

Not intending on writing about Lincoln, the history, to which Saunders was exposed 20 years earlier had left a lasting imprint. As though incubating over many literary lives, it experienced rebirth as Saunders gave voice to it, through Lincoln’s narration – and that of 166 ghosts. Framed mostly in dialogue, the form is near screenplay-like (one reason, maybe, why screen rights were purchased, so quickly), Saunders’ novel a distinct character from that of stories of similar length and scope. Indeed, the playful interplay between the protagonist and other-worldly actors give the story of love, loss, and grieving a mythical quality that lifts the narrative off the plane of the page into the reader’s consciousness.

The novel debut to universal acclaim but despite being the favorite among London’s bookmakers, Saunders was surprised to win – but he was far from speechless. In his acceptance speech, he offered a subtle repudiation of the new isolationism that has taken hold in the United States since Donald J. Trump was elected US President: “In the US we’re hearing a lot about the need to protect culture. Well this tonight is culture, it is international culture, it is compassionate culture, it is activist culture. It is a room full of believers in the word, in beauty and ambiguity and in trying to see the other person’s point of view, even when that is hard.”

Set during the US Civil War, and inside the head of a president, comparisons have been made to present day at which time, Americans find themselves pitted against each other to define their collective identity. Isolationism, indeed – racism, once again, has cast a shadow upon American society just as baffled pundits try to get inside the head of the current president.

Having channeled Lincoln with such empathy, wit, and intelligence, Saunders was asked a rather obvious question about the 45th president. Calling Trump, ‘The Anti-Lincoln,’ he told The Financial Times that, ‘Lincoln’s was a presidency of expanding generosity. He kept expanding the definition of equality pretty fearlessly, and I think now the present moment is more about constricting that — to say America is actually a white country, it’s actually a country for rich people, and so on.’

Commenting that despite having grown up in a deeply racist environment and, by the time of his death, Lincoln was a leader who had advanced to the point where it looked like he was going to advocate the vote for black men, Saunders contrasted this personality development with the nature of the current president: “Now you have got somebody who seems to delight in not learning, not growing, pissing people off, pulling in the boundaries of tolerance. So to me, it is almost a diametric opposition.”

THE AUTHOR

Already an acclaimed author in American literature, Saunders’ first novel was much anticipated after having authored several collections of short stories, essays, novellas, and a children’s book. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, McSweeney’s, and GQ. He also contributed a weekly column, American Psyche, to the weekend magazine of The Guardian between 2006 and 2008. Currently, Professor of Creative Writing at Syracuse University (where he, himself, studied the craft)

Saunders won the National Magazine Award for fiction in 1994, 1996, 2000, and 2004, and second prize in the O. Henry Awards in 1997. His first story collection, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, was a finalist for the 1996 PEN/Hemingway Award. In 2006 Saunders received a MacArthur Fellowship. In 2006 he won the World Fantasy Award for his short story “CommComm” and the lucrative Guggenheim Fellowship. In 2013, he was honoured with the PEN/Malamud Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award. Saunders’s most recent collection, Tenth of December: Stories won the 2013 Story Prize for short-story collections and the inaugural (2014) Folio Prize.

Well known for his inventive use of language, he feels his willingness to explore and exploit the forms and function of language derives in part from his scientific education and former career as a goephysics. He credits his early exposure to the works of Ayn Rand (some of the first fiction he recalls reading) with his decision to enter the field of engineering in college. “I read [her books] and I thought that’s what I want to do,” Saunders said in an interview with Guernica.

After earning his degree from the Colorado School of Mines, Saunders found himself reading a great deal of literature during a lonely extended stay in Sumatra where his employer was drilling for oil. The experience changed the trajectory of his career. In the same interview for Guernica, he described his desire to be an ‘Earth-Mover’ as the impetus behind his pursuit of a career in the engineering profession, simultaneously describing his distaste for “lisping liberal artsy leeches.”

Well, his love of literature turned his thinking around, and re-directed his career along a new line of trajectory, which would land him in the MFA program at the University of Syracuse. Studying Raynd, Hemmingway and Wolfe, his early works were largely imitative as he developed his own distinct voice and phraseology.

THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE

First awarded in 1969, the Man Booker Prize is recognized as the leading award for high quality literary fiction written in English. Its list of winners includes many of the giants of the last four decades, from Salman Rushdie to Margaret Atwood, Iris Murdoch to JM Coetzee. The prize has also recognised many authors early in their careers, including Eleanor Catton, Aravind Adiga and Ben Okri.

Man Group, an active investment management firm, has sponsored the prize since 2002. The rules of the prize were changed at the end of 2013 to embrace the English language ‘in all its vigour, its vitality, its versatility and its glory’, opening it up to writers beyond the UK and Commonwealth when their novels are published in UK.

Seen as a reaction to the establishment of the Folio Prize, the UK based prize, which was defined only by language, The decision has been met with controversy. Notable British authors like A.S. Byatt expressing their concern that the result would be dominance by big names at publishing houses at the costs of independents and lesser known writers. Indeed, observers have remarked Byatt’s star likely wouldn’t have been so brilliant, had the Booker not helped her parochial Anglocentric writing to a more international audience. On the other side, the New York Times opined that American critics looked to the Booker to help inform what was regarded as the best of literature outside the sphere of American literature – and this role had diminished since the rule change.

Announced in the same month that 1989 Booker Prize winner, Kazuo Ishishuro was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, Saunders’ Booker win brings to mind that others such as V.S. Naipal, Nadine Gorimer, JM Coetzee, and William Golding had achieved the same, in years past. Saunders’ widely acknowledged originality and influence upon American fiction as well as the array of literary honours awarded to him, might well leave him poised to follow in the footsteps of his most esteemed fellow recipients. Should this Buddhist’s karma bear such fruit, he might well acknowledge that in the arts, one can become an ‘Earth-Mover’ of a different kind, especially at a time when America finds itself in struggle to define its cultural existence.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine