Tremulous Reflections on Gandhi Jayanti

“Years back, I had read Lous Fischer’s acclaimed biography of Gandhi, and did a review of it for an English class assignment. I had also read Freedom at Midnight, which was the basis of the Masterpiece Theatre drama on the life of Mountbatten. I felt both books, written by non-Indians failed to appreciate the Indian perspective. To the Westerner, Gandhi was an exotic holy man who had almost comically outwitted his British masters like the character of the Japanese servant, Sakini who had run circles around the American occupiers of post-WW II Okinawa in Vern Sneider’s novel, Teahouse of the August Moon (and subsequent theatrical and film adaptations).”

<CALCUTTA>

<SB Veda>

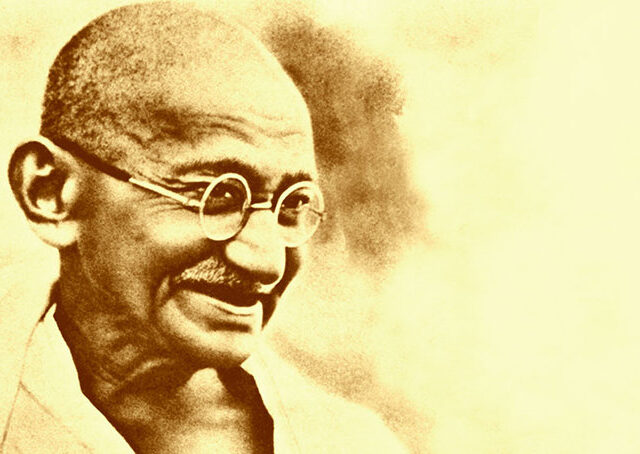

Reflecting on the legacy of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi on Gandhi Jayanti, the day of his birth, is no longer a simple celebration; one must separate the man from the legend.

India is not unique in the affliction of deifying its leaders – the British do so with Winston Churchill, the Americans with Abraham Lincoln – and, although alternative accounts of history have proliferated throughout the sub-continent, many Indians (perhaps even the majority) deify M.K. Gandhi. The first to do so was an eminent figure himself, no less than Asia’s first Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore. It was he who began referring to M.K. Gandhi as “Mahatma” – or Great Soul. The moniker has taken hold so compellingly since, that many believe Mahatma was M.K. Gandhi’s first name.

M.K. Gandhi’s populist Quit India movement has been credited with achieving Indian independence through non-violent non-cooperation. He is therefore considered to be ‘Father of the Nation’ in India. His image appears on every Indian note of currency. And his birthday, October 2nd, is a national holiday. Statues of Gandhi adorn most Indian cities, including the one from which I write, Calcutta (now Kolkata)

M.K. Gandhi first came to prominence as a young man, after being brought to South Africa to in 1893 in the employ of one Dada Abdulla, a trader for whom he provided advice as a lawyer, having just been called to the Bar in England. Once he came to understand the plight of Indians in South Africa due to institutional racial discrimination, he became an activist committed to fight racial injustices against fellow Indians.

Famously, while on a train from the port city of Durban, Natal Province to Transvaal, Pretoria, South Africa, despite holding a first-class ticket, a white person objected to a ‘coolie’ being seated there, claiming that non-whites were not allowed in first class. When staff were called, Gandhi produced his ticket, which only angered the white staff members who threw him off the train along with his luggage. This was seminal event in his life’s journey, which was to change it forever, committing him to use the law as a tool to achieve social change.

While in Transvaal, he observed that conditions for Indians were worse than in Natal (now Kwa-Zulu Natal). They were barred from owning property, and bound by curfews as well. Like Jews in Nazi Germany who had to wear the Star of David, Indians were required to carry identity passes, else face imprisonment. They were banned from even strolling on the footpath, which was the exclusive domain of whites; when Gandhi challenged this law, he was beaten by a policeman. The incident took place opposite the residence of the provincial President.

His first successful feat of activism was to get the railways to accept non-white passengers holding first-class tickets as having the right to sit in that section; the railway authority succumbed to the demand so long as the non-whites were “appropriately dressed”. He then mobilized the Indian community to protest a proposed bill that, if enacted, would take away the right to vote for Indians.

By then he had adopted non-violence; indeed, once on a train in South Africa, a policeman beat him in the presence of the other passengers because Gandhi refused to sit on the floor on a dirty rag. Witnessing this brutal violence, the white passengers implored the policeman to stop. Perhaps, that revealed to Gandhi the power that non-violence: to reveal the unjust nature of violence upon the human body, thereby compelling some force of authority to stop the injustice. So, he became committed to the principle as an article of faith.

A young Mohandas with wife Kastrba in South Africa – file.

The movement that came out of this non-violent non-cooperation he called Satyagraha or “holder of truths”. Combined with Gandhi’s natural political savvy, he mobilized a significant number to his causes, and improved the status of Indians in South Africa. He became an able organizer and learned how to ignite the passions of his flock to use their bodies to shield the broader population from oppression.

News of his exploits reached India. So, when he returned in 1915 to his home country, he was quickly recruited into the upper echelons of the Indian National Congress. Founded by the British, the INC was mainly committed to using legal means to gradually obtain greater autonomy and rights for Indians under British rule.

M.K. Gandhi along with younger leaders like Subhas Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Valabhai Patel, and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad transformed the Congress from a legalistic vehicle to one of populism. While many credit Gandhi for the move towards populism, Bose had already argued that the masses should be mobilized in a manner that transcended the legalistic modus operandi operating in the party at the time.

That said, Bose wanted to go further, and advocated independence by any means necessary, including armed revolution. He was extremely popular and won two consecutive terms as President of the INC. However, Gandhi was opposed to Bose on principle, having embraced non-violence and seen its power as an effective tool for social change in South Africa. Though Bose was President of the party, a slim majority (of one) of the executive committee of the Congress aligned with Gandhi’s views, handcuffing Bose from moving his agenda forward as President. He resigned his position (the last democratically elected leader of any variant of a national Congress party) and left India to pursue his vision outside the country.

M.K. Gandhi, clever as he was to recognize the power of populism, used the Congress party to mobilize the people into a populist movement against the British called the Quit India campaign. It was a simple strategy: the British governed by laws. Indians would break the laws they considered to be unjust – but refrain from violence when they were opposed by the security apparatus of the state. This involved taking beatings; many followers were critically injured, some killed. Congress leaders and activists were jailed, including Gandhi but, ultimately, they had to be released. Gandhi, essentially, used the laws of the British Empire against the British Raj. As the tactics proved successful, his popularity grew. And the Quit India campaign became an enormous mass movement.

Alternative accounts posit that the trials of the rebel Indian National Army (INA) heroes, former British Indian soldiers who were considered traitors to the Crown by engaging the British Indian Army on the battlefield in the years before independence under the leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose, had a profound effect of mobilizing Indians against the British, aiding significantly in Gandhi’s grassroots effort. In 1946, the British were dealing with a naval rebellion in the off the the coast of Bombay and even before that, Indian Army officers were secretly greeting each other with revolutionary and rival to Gandhi, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s greeting “Jai Hind” (Victory to India).

The British were seriously concerned that they would lose control over their colony. Indeed, when then Prime Minister of Britain, Clement Atlee, visited India in his retirement, he was asked to what degree Gandhi’s Quit India campaign had forced the British out of India. He responded by saying “MINIMAL”. The more prescient pressure against the Crown was the growing defiance of the Indian armed forces. It was no coincidence that the last Viceroy of India, Lord Louis Mountbatten who was charged with transitioning the colony towards independence chose an arbitrary deadline of August 15, 1947 – within a year of the naval uprisings, as the date on which power would be transferred from the British to the Indians.

Still, with Bose having disappeared several years before Independence, most believing he died in a plane crash in Taipei and nobody left to challenge Gandhi’s prime role in the Indian Independence movement, his position as ‘Father of the Nation” became cemented. Nehru and Patel had by then become committed Gandhians. Indeed, Nehru played an especially duplicitous role in causing Bose, someone who considered Nehru to be a friend, to resign from the Congress Party.

Interestingly, Bose and his brothers great respect for Gandhi, despite their political differences. Indeed, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s second eldest brother, Sunil Bose was the Mahatma’s cardiologist. I know this because when I interviewed Dwarakanath Bose, Sunil’s son and Netaji’s nephew, some years back, he shared his father’s medical notes on Gandhi with me. He helped keep Gandhi in good health, despite the stresses he was under, so he could continue his work as leader of the Quit India movement.

M.K. Gandhi (left) with the Indian National Congress annual meeting in Haripura in 1938 with Congress President Subhas Chandra Bose who resigned due to opposition from Gandhi-orchestrated opposition at the senior level (right) – Wikimedia

But that was not the end of the story. Opposition did come towards the end of the struggle. It came from Muhammed Ali Jinnah, who, once an apostle of Hindu-Muslim unity and fixture within the Congress party had joined the Muslim League to argue for the creation of a state for Muslims called Pakistan. Jinnah claimed that the Muslims of the subcontinent did not want to go from “British Raj to Hindu Raj.”

Initially, Gandhi strongly opposed the partition of British India. He even proposed that Jinnah be named India’s first Prime Minister as a compromise. By then, Nehru could see the Prime Ministership in his sights and Patel could not stomach being under Jinnah’s thumb. They could not accept Gandhi’s proposal. Indeed, as Maulana Kalam Azad wrote in his memoir, India Wins Freedom, that when partition was proposed, he had urged Gandhi advocate against it. Gandhi replied, “If Congress wishes to accept partition, it will be over my dead body. So, as long as I am alive, I will never agree to the partition of India. Nor will I, if I can help it, allow Congress to accept it.”

Gandhi’s powerful assertion reassured Azad. However, Azad writes of a two-hour meeting that Gandhi had with Mountbatten after their conversation, and that following this Patel had met with him. “What happened during this meeting, I do not know,” Azad, adding: “But when I met Gandhiji again, I received the greatest shock of my life to find that he had changed. He was still not openly in favour of partition but he no longer spoke so vehemently against it. What surprised and shocked me even more was that he began to repeat the arguments which Sardar Patel had already used.” Patel had accepted partition, and felt that if there should be a country created for Muslims in the sub-continent, then India should be declared Hindu. This position has endeared Patel, though a Congress leader, to the Hindu right even today.

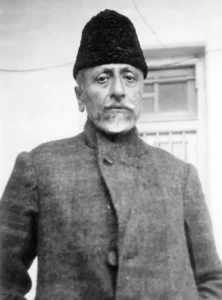

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, though a Mullah, born in Mecca, he was a staunch supporter of secularism and opposed to the partition of India. Sadly, he lost the political argument. – file

Azad felt that Gandhi’s proposal that Jinnah be asked to form the first government of an undivided India might save the subcontinent from partition but noted, “Unfortunately, this move could make no progress as Jawaharlal (Nehru) and Sardar Patel were opposed to it vehemently. In fact, they forced Gandhiji to withdraw the suggestion.”

This narration by Azad runs counter to the statesmanlike presentation of Nehru and Patel portrayed in Richard Attenborough’s film, Gandhi, which was very loosely based on Louis Fischer’s biography of Gandhi minus any critical analysis of any of the Indian figures in the independence movement.

With Gandhi abandoned, in the end, by his lieutenants, it was only left to Congress and the Muslim League to decide on the nature of partition. Only Azad predicted that the consequences would be devastating for India. He was proven right with ten million souls displaced and communal strife taking the lives of as many as two million people.

While Nehru gave a stirring speech from the Red Fort in Delhi on the August 15th, 1947, the date when India was granted Dominion Status by the British, Gandhi was in Calcutta on his way to Noakhali, which became part of Pakistan to prevent attacks on Hindus by Muslims. He had protected Muslims in what became India against the Hindu mobs. On Independence Day, he fasted.

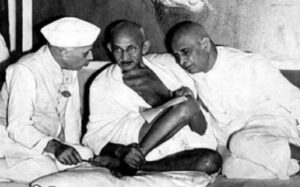

Iconic photo of Gandhii (centre) with his closest lieutenants, Jawaharlal Nehru (left) and Sardar Valabhai Patel (right). Though loyal to a fault during much of the Independence struggle, in the end, they abandoned him on the issue of partition. The lure of political power had overwhelmed their obedience to their mentor. – file

The rest, as they say, is history.

However, in recent times, Gandhi’s status as ‘Great Soul’ has been challenged. In 2018, a statue of Gandhi at the University of Ghana was taken down on grounds of racism. As South African émigré from India, Gandhi had espoused such racially charged views as saying that those of Indian ancestry should not marry or have relations with “black” Africans. Indeed, while he was there, he supported the whites against the Zulu rebellion, encouraging Indians to volunteer in the armed forces against the Zulus. He, himself, participated in an Indian ambulance corps, which he organized, to help in the conflict to put down the black tribes. He had supported the British in the Boer War because he felt loyalty to the Empire would improve the position of Indians in the hierarchy South African society, but his support failed to garner additional rights for the community. Consequently, he sharpened his focus.

He recounted his reasoning for supporting white against black in his famed autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth:

“A genuine sense of loyalty prevented me from even wishing ill to the Empire. The rightness or otherwise of the (Zulu) ‘rebellion’ was therefore not likely to affect my decision. Natal (province) had a Volunteer Defence Force, and it was open to it to recruit more men. I read that this force had already been mobilized to quell the ‘rebellion’.

I considered myself a citizen of Natal, being intimately connected with it. So I wrote to the Governor, expressing my readiness, if necessary, to form an Indian Ambulance Corps. He replied immediately accepting the offer.”

It is telling that he put the word “rebellion” in sneer quotes, repeatedly, indicating a certain derision of the Zulus in their uprising against their white ‘masters’. That he actively mobilized Indians to help in the effort to defeat the Zulus demonstrates that he was no friend of the native African. It is no wonder that Africans have reassessed their regard for M.K. Gandhi as a result, though his activities in India have proven him to be an inspirational anti-colonial figure to various peoples. American civil rights leader, Martin Luther King, for instance, considered him an inspiration.

Whether it is fair to judge Gandhi for his views on black Africans is a question for the people who’ve read the history to decide. I will decline to give an opinion for the purpose of this piece. It is, after all, Gandhi Jayanti.

GANDHI’S PERSONAL LIFE

M.K. Gandhi’s personal life, especially in terms of his views on sex and sexuality have come under fire over the past few decades. His tests of celibacy which included sleeping naked with his similarly unclothed teenaged grandnieces as well as sleeping and bathing with his attractive personal physician and sister of his secretary, Sushila Nayyar, are difficult to reconcile with his exalted status. He wrote of the experience with Dr. Nayyar, excusing himself by stating: “While she is bathing I keep my eyes tightly shut,” he said, “I do not know … whether she bathes naked or with her underwear on. I can tell from the sound that she uses soap.”

Seen in today’s light, these practices can be considered criminal as pertaining to his grandnieces and abusive in regard to Dr. Nayyar (due to the imbalance of power between them, her being an ardent devotee of his). Hence, Gandhi’s legacy, which was burnished by Richard Attenborough’s hagiographic film called Gandhi, has become seriously undermined with literature that has highlighted facts about Gandhi’s personal life and views on various issues.

GANDHI AS A POWERFUL SYMBOL

When I reflect on Gandhi’s legacy, I recall a period during which I, as undergraduate student at Carleton University, attended The Learned Societies Conference, a meeting of academics across Canada and internationally, which was held one summer at our campus during which India was the focus of the various symposia and cultural events organized around the event. Among the lectures I attended was a talk given by an American professor of Indian origin on “Gandhian Economics.”

The local Mahatma Gandhi society had been a sponsor of the lecture and then High Commissioner of India, His Excellency Prem K. Budhwar had been invited as guest of honour. The professor’s central thesis was (if I may generalize) that since socialist India had been implementing economic principles based on Gandhian edicts, “Gandhian Economics” had led to India’s economic woes. Gandhi was a lawyer by training and anti-urban in his thinking; he was not an economist but had rather eccentric and isolationist views standing against international trade. He also believed people should live in poverty as he did: spending to fuel the economy was considered wasteful by him. (It is worth noting that Gandhi’s version of poverty involved living in mansions provided by the affluent Birla family, pre-independence, and post-independence, former freedom fighter and India’s first Home Minister, Sardar Valabhai Patel once said that it cost the Indian state a fortune to keep Gandhi in poverty.)

The speaker had used historical data to support his position. By that time, India had begun its liberalization program under Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister Manmohan Singh (who went on to abandon his own economic agenda when chosen by Congress President Sonia Gandhi and her circle to serve as India’s Prime Minister a decade, later). Hence, the speaker’s talk, more historical in nature, didn’t represent India’s upward trajectory as a growing economy.

The High Commissioner was angered that the professor had not used the latest economic data, which apparently, was in possession of the High Commission – and thereby the speaker was mischaracterizing India as being reflective of the pre-liberalization period. He also took umbrage with the thesis in general as being insulting to the ‘Father of the Nation’ nor did he accept that the Indian intelligentsia and political class were so blindly bound to Gandhian beliefs that Gandhi was behind their policy decisions. So, not being able to stand to listen to the lecture until the end, he left midway through, in a huff. A throng of Indian origin sycophants followed suit, some hurling insults at the soft-spoken scholarly speaker who had been invited to speak at our university.

I and the friend who had attended with me moved to the front of the auditorium to show our support for the professor’s right to present his views as we both felt that a university, in particular, is a place for freedom of expression and exchange of ideas. The group who left were basically trying to censor him, while exercising their right to hurl offensive epithets at the genteel professor.

The speaker then, said that if the audience found his talk offensive, he would highlight some of the positives of “Gandhian Economics” and proceeded to talk about the aspects of Gandhi’s economic principles which strengthened India’s economically and politically.

At the conclusion of the talk, when it is customary that a vote of thanks be given, the organizer – an official of the Mahatma Gandhi Society – took the opportunity to attack the speaker whom he had invited. He emphasized that when he invited professor, he had no idea that his guest would insult Gandhi-ji and assail his legacy. He ‘apologized’ to the audience for his mistake in arranging the lecture. By then those who had apparently taken offence were long gone. Indeed, one of the spectators, a professor of political science said, “This conference is for the presentation of scholarship and exchange of scholarly ideas – it is not a forum for the Indian bureaucracy to berate academics into submission.”

The memory for me is instructive: the topic did not touch upon Gandhi’s views on race or sex (about which, for a “natural Brahmachari” he seemed to talk and write a great deal). It was a seminar on a rather non-controversial and somewhat dry subject: economics. Frankly, it was the last type of forum where I would have expected an eruption of squabbling. The Learned Societies events were such polite and stately affairs that what had transpired was the equivalent of a riot!

I learned then what a symbol Gandhi had become that thousands of kilometers away from India in a country where Indian origin peoples formed a small minority, Gandhi was a powerful figure evoking passionate loyalty.

Years back, I had read Lous Fischer’s acclaimed biography of Gandhi, and did a review of it for an English class assignment. I had also read Freedom at Midnight, which was the basis of the Masterpiece Theatre drama on the life of Mountbatten. I felt both books, written by non-Indians failed to appreciate the Indian perspective. To the Westerner, Gandhi was an exotic holy man who had almost comically outwitted his British masters like the character of the Japanese servant, Sakini who had run circles around the American occupiers of post-WW II Okinawa in Vern Sneider’s novel, Teahouse of the August Moon (and subsequent theatrical and film adaptations).

Fischer to his credit analyzed how an incident in Gandhi’s youth, when he was a newlywed had influenced his views on sexuality – and boiled it down to guilt. He recounted how Gandhi was massaging his father who was gravely ill. Indeed, the family considered him to be on his deathbed. A young Mohandas could not keep thoughts of sex out of his mind, so he got someone to relieve him while he left the room and sought out his wife Kasturba. They had sex. When Gandhi returned to his father’s bedroom, he found his other family members weeping, for his father had died. He blamed his uncontrollable sexual desires to have robbed him of the privilege of comforting his father as he passed from this world. This made the act of sex and the desire for it a fierce form of wickedness. That he would have been infused by the dogmas of Victorian-influenced Christian morals held by the colonizers ironically added to his guilt.

Though he went on to have four children, Gandhi took a vow of celibacy at the age of thirty-eight. In the Ashram, which he established in India as well as the communal farms he founded in South Africa, he required men and women to sleep in separate dorms, including those who were married. He was the only married man to be permitted to stay at these premises and sleep beside his wife. He even encouraged married couples to practice celibacy – and discouraged marriage in others. He forbade his young female physician Sushila Nayyar from marrying. As stated, he observed her bathing and slept in the same bed as her. Marriage, quite likely would have ended these practices with the potential objections of a husband entering the debate on testing Gandhi’s celibacy.

There are many who regard Gandhi’s tests of carnal instincts as being a “true form of tantrism” – that Gandhi was so holy, he was beyond human desires – refusing give into temptation while living ensconced in it to prove. Others counter by asking why he didn’t bring prostitutes into his bed to test his celibacy rather than his grandnieces and other followers in this fashion. Surely his benefactors would have financed the project! Perhaps this would have shed a scrutinizing spotlight on the practice – but nobody could question Gandhi sleeping in the same bed as his female relatives (probably none of his other followers knew the circumstances: that he and they were naked). Those critical of Gandhi posit that his movement was cult-like. So, to closest devotees, he could do no wrong. Afterall, is a saint not closest to God?

He, himself, asserted resolutely that he was not a saint but a politician trying his hardest to be a saint. Still, many recognize that were it not for this unflinching devotion of his followers, Satyagraha would have never worked. Non-violent protesters would have cowered instead of facing the blows and bullets of British-commanded soldiers and policemen. They needed to believe in something greater than the vulnerability of the human form, rise above their mortality, and be willing to die for their beliefs.

Gandhi statue toppled in 2018 in Ghana, two years after donation by the Indian Government, over claims of racism by the iconic activist and Indian independence leader – Emanuel Driven, YouTube

Sometimes it takes a madman to change the world for the better. Those who excuse Churchill’s pathological hatred of Indians, which was so intense that he would allow three million Bengali Indians to die in a famine while he exported Indian wheat to allied troops in North Africa, argue that his genocidal racism should be set aside. They say that it was his stubborn character, his unwavering exceptionalism that made him such an inspirational leader during World War II. While there was a darker side to such intransience, he had shown strength where his predecessor had shown weakness at a time when he was called a dangerous warmonger. Still, applying that argument, Atlee’s reasonable nature as his successor as well as US President John F. Kennedy’s restraint during the Cuban missile crisis, would be regarded as frailty.

I realized then as now that while Gandhi, himself, was very calculating and almost cold in his plotting against the British and other political adversaries, the reaction he evokes from the general public is tremendously emotional. Followers, deify him and in doing so will leave no space for discussing Gandhi as a human being with both incredible talents and deep flaws. Criticism is off the table. Similarly, his detractors have become visceral in their denunciations of him, perhaps because sexual abuse and abuse of power against women, especially after the advent of the #ME TOO movement, have come to be viewed as unacceptable under any circumstances and regardless of the identity of the perpetrator – even someone called a ‘Great Soul’.

To his credit, Gandhi did not hide his inner conflict. He wrote about his struggles. Indeed, the full accounting of his thoughts may have been so injurious to his legacy that his followers burnt some volumes of his writings.

M.K. Gandhi wrote about everything that came to mind – from Tolstoy to the frequency of his bowel movements. This led one famous contemporary Gandhian, Ramchandra Guha to state, at a literary festival in Calcutta, where he knew his words would make the headlines, that “Gandhi was a more prolific writer than Tagore.” Had I been on stage with him, I would have simply countered that the ‘historian’ was right: it was simply a matter of quantity over quality. But Bengalis took the bait, and Guha was in the news, getting publicity he could otherwise never buy.

Guha and I, by the way, once had a conversation over lunch at the same literary event (only during another year) at which we were both delegates. I was late getting a seat the table in the restaurant designated to feed delegates at the Taj Bengal hotel in Calcutta at lunchtime. So, there was basically nobody left in dinging hall. And, then Guha sauntered in, scanning the buffet, he ended up requesting the General Manager, who was trailing him, to get someone to whip him up a vegetarian pasta. (This led me to believe he was a vegetarian – before he turned beef-eating into an apparently delectable form of human rights activism.)

He took a seat at my table, though I hadn’t invited him to do so. (As an acclaimed author, perhaps he assumed anyone would welcome his company.) He could see that I was writing an article as I ate, and asked me about it. I told him it was about the then Congress government’s refusal to declassify files on Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

This prompted Guha to say that he was glad that Nehru had become India’s first Prime Minister rather than Bose, tempting me into a debate in which history would take on the hypothetical. Unlike other Bengalis who were stirred by his comments on Gandhi as writer vs. Tagore, I did not take the bait. I responded that he was certainly entitled to his opinion, though I believed that Nehru made many mistakes in especially on Kashmir and foreign policy. “Still, would Nehru have been able to accomplish all that he did had Gandhi not been killed when he was?” I said.

This abruptly ended the debate desired by the eminent Gandhian and allowed me to eat in peace and finish my article. When we did speak, it was very civilized and limited to the festival and books in general. By observing Gandhians, I had learned by then how to handle controversies in Indian history. So with memory of what invoking Gandhi’s name did for me at that lunch table at the Taj Bengal hotel in mind, I commemorate him, today.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine