Monsoon Reads & Autumn Words

“Through books our intellect is engaged with our emotions and imagination – and so, perhaps more so than any other art form, by reading we evolve our thinking about a humanity as a whole.”

Reviews to help turn the page on 2015:

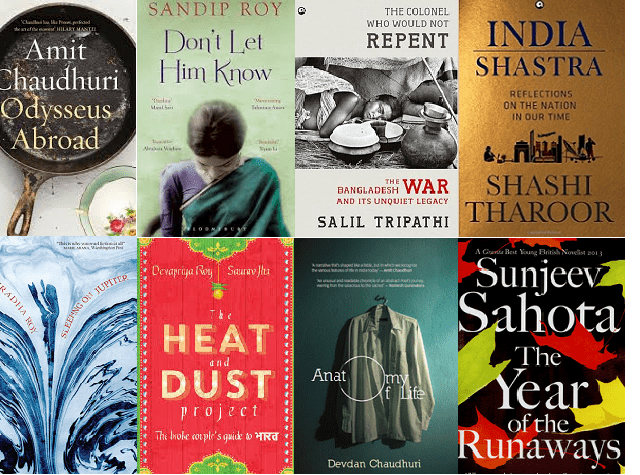

Odysseus Abroad by Amit Chaudhuri, (Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of Penguin India 2014)

Don’t Let Him Know by Sandip Roy (Bloomsbury 2015)

The Silk Roads – A New History of the Ancient World by Peter Frankopan (Bloomsbury, 2015)

Anatomy of Life, by Devdan Chaudhuri (Picador India, 2014)

Leaving Home With Half a Fridge by Arathi Menon (Pan Macmillan, India 2015)

Sleeping on Jupiter, by Anuradha Roy (Hachette 2015)

The Heat and Dust Project by Devapriya Roy and Saurav Jha (Harper Collins India 2015)

Modi Demystified by Ramesh Menon (Harper Collins, 2015)

The Colonel Who Would Not Repent:The Bangladesh War and its Unquiet Legacy by Salil Tripathi (Aleph, 2014)

India Shastra: Reflections on the Nation in Our Time by Shashi Tharoor (Aleph, 2015)

Indo-Anglian Writing: The Story Continues

Whether, like us, you are stifled by dragging monsoons or suffering the hangover of spent summer elsewhere, there are many books published in the last twelve months that can provide comfort. We’ve reviewed a selection that contains a decidedly Calcuttan focus.

Perhaps more so than at any point in history, English language literature rooted in Calcutta has never been so varied. The 2015 season (beginning in late fall, 2014 – yes books appear to be like cars in that respect) saw the debut of two new voices from the city, one of whom is especially strong, namely Sandip Roy. His novelistic collection of short stories, Don’t Let Him Know, looks at the fragile construction that is the middle class Bengali family from different angles, offering a fresh and vivid account of the twisted middle in middle class. But no recap of the year would be complete without mentioning the engaging and revealing train ride that Anuradha Roy takes us on in Sleeping on Jupiter. In delightful prose, with both humour and pathos, she takes on gender parodoxy in Indian society (longlisted this year for the Booker) and gives us a memorable journey. Never more epic was the mundane as in Amit Chaudhuri’s Odysseus Abroad, which relates the Bengali diaspora experience in a way that blurs the boundary between fact and fiction. We join a Bengali Indian foreign student of English Literature who seems the mirror image of a younger Chadhuri on a minutely observed stroll through London – all in a single day. With it we move through that character’s migrations and the wanderings of his mind. In the process, the multi-talented Chaudhuri completes a kind of career arc in the novel genre.

There is of course much more to look back on from the perspective of Global Calcuttans, notably: Amitav Ghosh finished his Ibis trilogy in a Flood of Fire; Devdan Chaudhuri arrived on the literary scene to dissect archetypal characters in Anatomy of Life; and Saikat Majumdar took off with Firebird, his second novel – a subtle and elegantly narrated story about life and death in Bengali theatre.

In the last two years, successively, two Bengali Diaspora writers were shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize (Neel Mukherjee and Jhumpa Lahiri). Interestingly, both their books detailed a Calcutta during the same period: the turbulent years of the Naxalite movement. This year has seen the number of novels set in Calcutta (at least in part) multiply.

In the wider diaspora, writing is by no means less than. A relatively new voice demonstrated his growing confidence in The Year of the Runaways, a tale of Indian immigrants living in Shefield. Sunjiv Sahota’s second novel has made the Booker shortlist over some heavily favoured titles. The acclaim garnered by this British Asian’s book is surely an indication that journeys, those of migration, are still of interested to critical readers. Indian-American, Akhil Sharma gave us a haunting tale of family dysfunction amid tragedy in the novel, Family Life, last year, and it was awarded the Folio Prize this summer. Sharma followed up his dark and forceful debut novel An Obedient Father (winner of the Pen/Hemingway Prize) with a poignant semi-autobiographical novel twelve years in the writing. The story is a gut-wrenching commentary on the American dream (from the Indian perspective), narrated in prose that is refreshingly free from exoticism or sentimentality.

These days, non-fiction is considered the star of Indian Literature. Though renowned editor, Ian Jack calls this nonsense in his introduction to the last India issue of Granta (130), one can understand why this view sprung up. The literary world was taken by storm in the ’80s and ’90s by the likes of Ruth Prawer Jhabwala, Anita Desai, Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth and others. Today, fewer novels out of the region’s cultural sphere are talked about as ‘masterpieces’ but dramatically more voices have populate its space.

The growth of Indian publishing in the English language and the tastes of Indian readers have paved a more populist path for writers in India. More Indians are reading in English than ever before – but what are they reading? How might their tastes and appetites evolve? Whatever the answers, expansion cannot be bad for writers as a whole, though literary types will certainly feel increasingly marginalized. That said, this is not unique to India – it is a worldwide phenomenon.

Non-fiction traditionally consisted of two sets of books: academic types, and the biography. Memoir and commentary were scarce. Tagore wrote My Reminiscences, which many would know from Calcutta. Another Nobel Laureate, V.S. Naipaul wrote nonfiction commentary based on his experiences that made many Indians, ever conscious of self-perception, cringe. Nirad Chaudhuri while lesser known would fall into this category, too.

Today, Indian non-fiction is varied and layered. Some books of particular interest to us were Salil Tripathi’s The Colonel Who Would not Repent, Shashi Tharoor’s India Shastra: Reflections on the Nation in Our Time, and The Heat and Dust Project by husband-wife duo Devapriya Roy and Saurav Jha. Triphathi narrates a complex history and socio-political dynamic that is of great relevance to contemporary global conflict. Tharoor offers up a prolific array of expositions that demonstrates his range and depth of knowledge of various issues – all with trademark humour. And, the young wife-husband team of Roy and Jha have ostensibly written a travelogue but it is so much more.

A magazine like ours is limited in our coverage but we have tried to include an eclectic mix from all the major publishers, including one self-published fictional travelogue by the retired Canadian scientist, Subhas C. Biswas called India – Land of Gods. All told, the state of Indian literature is strong, and with the advent of e-books and online magazines, becoming increasingly diverse.

A brief word about Jhabwala , we consider much of her writing as Indian. Though she is of European extraction and migrated to India, it is worth noting that her most acclaimed novel for which she was awarded the Booker prize was an Indian tale.

Categories are becoming as blurred as identity with literature becoming increasingly transnational. The traditional slots within which books have been classified are no longer so concrete. This too is a good thing, for there is nothing so deadening to intellectual life as the rock of certainty. Great literature helps us to examine life, ask important questions, see ourselves and the world around us through a new set of perspectives. Through books our intellect is engaged with our emotions and imagination – and so, perhaps more so than any other art form, by reading we evolve our thinking about a humanity as a whole. The page truly does have the power to transform the self. With that, we implore you to read on…

Sid Atanya

Editor-in-Chief

&

SB Veda

Contributing Editor

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine