“Rushdie Attack is Assault on Freedom of Speech”: Writers

SB Veda CALCUTTA

16 August, 2022

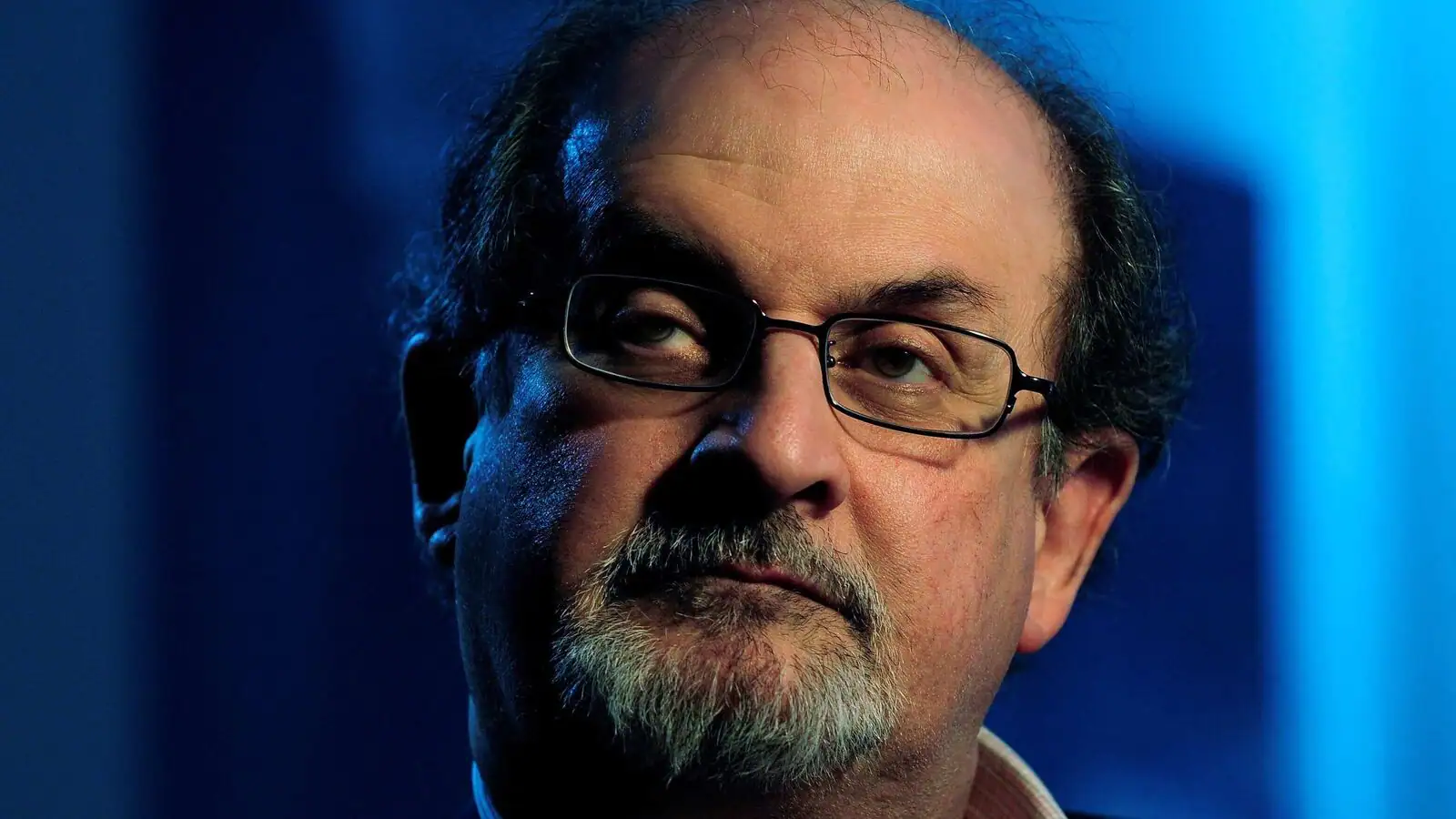

The shocking assassination attempt of Salman Rushdie at an upstate New York literary event where, ironically, Rushdie was speaking on giving writers in physical peril asylum in various cities has underpinned the threats to freedom of expression, which continue the world over.

Suzanne Nossel, the chief executive officer of PEN America, said the nonprofit literary organisation was “reeling from shock and horror” at the attack. Rushdie is a former president of PEN America, which advocates for writers’ freedom of expression around the world.

“We can think of no comparable incident of a public violent attack on a literary writer on American soil,” Nossel said. “Salman Rushdie has been targeted for his words for decades but has never flinched nor faltered. He has devoted tireless energy to assisting others who are vulnerable and menaced…We hope and believe fervently that his essential voice cannot and will not be silenced.”

Ian McEwan, the Booker Prize winning author, and friend of Rushdie said the “appalling attack” represents an assault on freedom of thought and speech.

“These are the freedoms that underpin all our rights and liberties,” he said. “Salman has been an inspirational defender of persecuted writers and journalists across the world. He is a fiery and generous spirit, a man of immense talent and courage and he will not be deterred.”

In the wake of the attack, we recall our raison d’être: The year was 2013, and Rushdie had been banned from entering Calcutta – a city known for its literary heritage at a time when I was a delegate at a literary festival in the city. Expecting opposition to the ban from the writers present, I was aghast to a group of the writers discussing the ban as positive. At the same time, one of India’s most esteemed intellectuals was escorted out of the Jaipur Literary Festival and hauled before a judge in Delhi for making statements that repeated out of context by the India media. This too was applauded by the group I had witnessed discussing these issues. Our small magazine was co-founded in part because of the threat to freedom of expression observed in Kolkata.

At the time, the writer’s Booker Prize winning novel, Midnights Children (indeed, it had been awarded the Booker for Best British novel of the past 25 years in 1993) had been made into a film that just come out, and Rushdie – who had also written the film’s screenplay – was in India promoting the adaptation. He had planned to promote the film and attend events in West Bengal.

Due to Rushdie’s exit from the Jaipur Literary Festival the prior year as a result of threats made by Islamic extremists, the organizers of both the Kolkata Literary Meet and The Kolkata International Book fair were deliberately careful in mentioning their intention to have him participate, conspicuously leaving him off their invitation lists. Indeed, then Chief Ministerial hopeful, Mamata Banerjee had proclaimed that should she ascend to the throne of West Bengal, she would certainly prevent the award-winning writer from entering the city, much less participating in any literary event. Still, Rushdie was to participate as a “surprise guest” at both due to the timing of the release of the film version of Midnight’s Children, and interest from organizers to manage to host him in a city known for writers and when a competing festival, the year prior, had buckled under the pressure, resulting in Rushdie’s removal from the venue.

Indeed, the Director of the Kolkata Literary Meet had paid for Rushdie’s plane ticket to Calcutta, and arranged to his lodging at the Taj Bengal Hotel – deliberately at a distance from where the rest of the delegates were being housed, which was the ITC Sonar Bangla (walking distance from the venue at the Kolkata International Bookfair).

A delegate and moderator at the festival, last year, I was also interviewing delegate writers for a foreign publication. I was told on January 29th, 2013, to make myself available relatively early in morning of the next day for transportation to the Taj Bengal hotel for interaction with a secret guest. I asked if the guest might be the famous novelist who could not be named. The press coordinator told me, “It’ll be worth your while – I guarantee it!”

We all found out on the morning of the 30th that Salman Rushdie’s plans were aborted when he claimed that the organizers had pulled his invitation amidst pressure from the police and politicians. The press coordinator called me and admitted that the special guest was Rushdie, and he was not coming. It came out later, according to an anonymous quotation of a minister in Ms. Banerjee’s government in the Calcutta daily, The Telegraph, that “The chief minister expressed her displeasure and instructed the chief secretary and the home secretary to deal with it strongly,”

Rushdie, in a statement, had said he was informed that the police would refuse him entry and that the decision was at the behest of West Bengal state’s chief minister, Mamata Banerjee. This came, after Rushdie’s hosts, essentially threw him under the proverbial bus, saying, ““We have not had a single exchange with Rushdie about coming to Calcutta…. Now if he wanted to come to Calcutta, we are no one to stop him. But we never invited him.”

Rushdie countered by stating he had e-mails and plane tickets sent to him by them as proof of their lie. “Finally re Kolkata: the lit meet organisers are lying when they say I wasn’t invited. I have e-mails and plane tkt (sic) sent by them to prove it,” Rushdie tweeted.

In a separate tweet, the author slammed the police for giving his itinerary to the “press” and calling Muslim groups

Rushdie’s assertions align with someone whose name did appear on the organizer’s program, namely Deepa Mehta, the film’s director. The following day, she tweeted: “[Rushdie] was going to be a surprise guest… Lit meet paid 4 his tkt [Mumbai-Kolkata flight ticket],” This was retweeted by the author.

Mehta and the producer of the film both boycotted the event out of protest, leaving actor Rahul Bose to represent the production.

Defending Rushdie, the elder statesperson of the Indian literary and social activism community, Mahasweta Devi, said: “Kolkata has been an open city for all kinds of cultural activities and people. It is unfortunate that he [Rushdie] could not come. He should have been welcome to the city with all the respect.”

Writer and journalist, Ruchir Joshi wrote a piece in the Calcutta daily, The Telegraph, which shamed the organizers and Calcutta’s people. He wrote, “It is an episode that does not show the city, the so-called cultural capital of India, in a favourable light. One also wonders how the city would appear in Rushdie’s fiction if the writer, who has always defended free speech at the risk of his life, had at all written about it in a significant way. ‘I write to save my life,’said the author.”

The statement is all the more prescient in light of the recent attempt to put an end to the writer’s life.

Joshi also contended that the state, having become aware of Rushdie and the Literary Meet/ Book Fair’s plans to surreptitiously include the author in the programmes held at their shared venue, dispatched police to inform extreme Muslim groups of the plans, thereby manufacturing the ‘indigenous opposition’ to the author, which resulted in the gaggle of loudmouths who showed up at the airport to ‘protest’.

While some like those mentioned above, defended Rushdie’s right to enter the city, speak and engage with audiences, my observation was these were in the minority among the literati. The group whom I observed were gleefully laughing about Rushdie’s shunning. Indeed, on that day, another incident occurred – one again at Jaipur. India’s foremost public intellectual, author, Ashis Nandy had said some things that had been taken out of the context of the panel discussion in which he was participating on the subject of corruption. He mentioned that the corruption of the elites are so sophisticated, they are not exposed, and that the downtrodden must act in corrupt ways to rise in society.

So, Nandy took it optimistically that when high percentages of Dalits, OBCs and SCs are corrupt, he saw it as the downtrodden finding a way to play the same game of the elites in attempting to redress the balance of inequities in India. The statement, which the press reported as being anti-Dalit/OBC/SC, got him thrown out of the festival and dragged in front of a judge. A First Information Report (FIR) prima facia criminal case was lodged against him, and he very nearly was thrown in jail. When I mentioned that this was an afront to freedom of speech, the group I was chatting with (which included an Oxford professor, and novelist, another novelist, and a member of the mainstream broadcast media) were fully in support of locking up the seventy-five-year-old intellectual.

From 2016 to the end of 2020, UNESCO recorded 400 killings of writers/journalists, while this is a down 20 percent decrease from the previous five-year period, writing continues to be a perilous calling.

Last Friday’s assassination attempt on Rushdie took place more than 33 years after Iran’s late leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa, or religious decree, calling for his death. The author, who currently lives in the United States, had been living under police protection for many years because of threats to his life.

The Global Calcuttan Magazine

The Global Calcuttan Magazine